Is The Deep Ellum Community Watch Facebook Group Helping Curb Neighborhood Crime? Or Is It A Forum For Fear-Mongering And Public Shaming?

With the Dallas Police Department both understaffed and underfunded these days, it’s not surprising to hear that some communities around the city have taken it upon themselves to self-police their own turfs, using social media to warn and alert their members to the hazards and problems that might be arising within their neighborhoods.

But how much good do these groups do, really? Are they safe spaces to discuss legitimate concerns? Or are they forums that prey on unfamiliarity and fear to push specific agendas?

For two years now, a private Facebook group known as the Deep Ellum Community Watch has taken it upon itself to dictate which kinds of behavior are and aren’t acceptable in the revered Dallas neighborhood of Deep Ellum. Over that time, the page has established itself as a hub of neighborhood-specific information for its 2,600-plus members — a group that includes Deep Ellum dwellers, workers, regulars and outside voyeurs. It’s a great place for finding out about an act of vandalism that occurred overnight — and a fine resource, too, for finding outrage over someone sneezing a little too closely to someone else’s drink.

Point is, it gets used a lot.

Journalists use it to find stories, bar owners and bouncers use it to alert one another to problematic trends and patrons spreading across the neighborhood, and police officers and even city council member Adam Medrano frequent the page to answer questions about criminal and municipal activity.

Above them all are the page’s administrators. Raine Devries — a “nationally recognized journalist covering the motorcycle industry,” according to her own Facebook page — is one of 13 moderators who bounces Deep Ellum Community Watch’s door, deciding who gets in and what makes it to the page. To her, the page’s benefits are obvious.

“You’ll have guys and girls working the front doors [of Deep Ellum bars] for security, and when they’re at the height of activity on Fridays and Saturdays, they can’t hear their phones,” Devries says of the page’s benefit to the community. “However, they can watch what’s going on — so, if one venue is having an issue with someone that’s underage and trying to get in, they can post an update and it’ll filter throughout the neighborhood so the other people working the doors can be on the look-out. It’s beneficial to let people know if there’s someone in the neighborhood that’s acting less than stellar.”

There are no readily available stats on how pages like DECW affect the crime in a given neighborhood, but there’s little doubting the benefit of sharing information on potentially dangerous situations within a community. When used properly, University of North Texas sociology lecturer and undergraduate program director Helen Potts thinks pages like Deep Ellum Community Watch can be have a positive effect on a community, acting like technology-aided versions of the neighborhood watches of yesteryear.

“Community policing relies on social capital, so if people are coming together in the neighborhood to take care of their neighborhood, it usually creates a fabric of community,” Potts says. “The main point here is that with community policing, there’s trust involved. You learn people’s names, and it starts to become like it used to be 30 or 40 years ago where you knew who was home and what they were doing. Anytime you have that, crime rates are going to go down.”

There’s some question, though, as to how much the Dallas Police Department itself uses the information shared in Facebook pages like these in its own efforts to curb crime. No fewer than two police officers regularly comment within the page’s discussions, and DPD is known to have used social media monitoring software for certain specific usages in the past, but DPD did not respond to multiple requests for comment on this story about how — if in any official capacity, anyway — it uses Facebook community pages like DECW to monitor areas within its jurisdiction.

Not that any of that matters to DECW, of course. Its users ostensibly operate with information and education, reporting suspicious behavior as they see fit. But with no clear training or protocol for the users of pages like DECW, “suspicious behavior” suddenly becomes a broad catch-all term. And the issues that users feel compelled to share with one another indeed span a wide range.

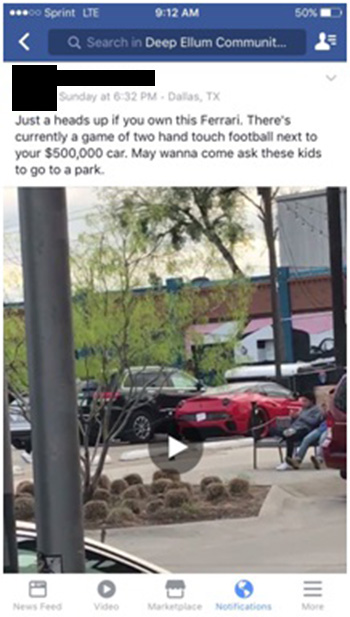

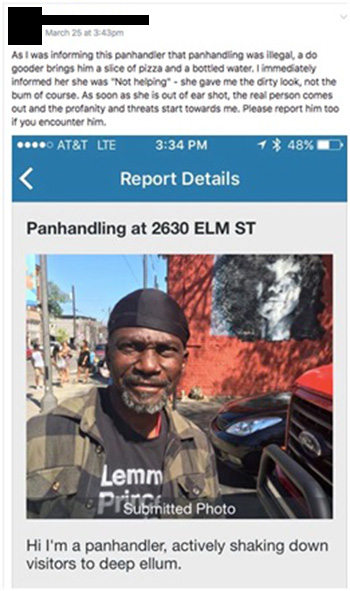

These are just a few examples of the kinds of posts that are regularly shared in the Deep Ellum Community Watch page:

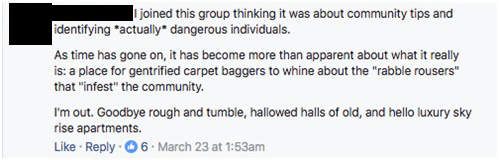

Depending on your perspective, those posts can be read as genuinely helpful, oddly angry and/or curiously skeptical. It’s no wonder, then, that another popular topic of conversation in the page is what good these kinds of posts bring:

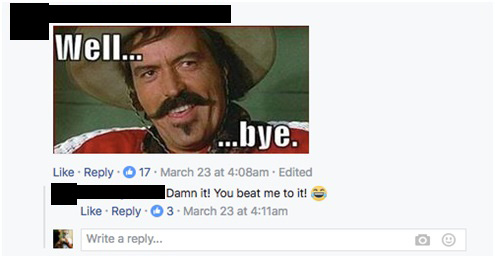

Following that particular comment, there was little to no discussion about whether the group’s efforts are right or wrong; instead, one of Devries’ fellow administrators simply posted the below, somewhat celebratory meme at an opposing view leaving the group:

That concerned poster is not some aberration, though. Many of the page’s users openly question whether the people in charge of Deep Ellum Community Watch take their jobs as gatekeepers a little too seriously — and, in turn a little too dangerously, by spewing silly-generalizations, over-exaggerations or shutting out any dissent.

One of the many followers of Deep Ellum Community Watch who questions how much good the group actually does is Dallas event promoter Greg Barrett, who has been throwing events in Deep Ellum and other parts of the city for the better part of 20 years now. Barrett worries that the group is too cavalier in its attitude toward the neighborhood’s homeless and mentally ill, and questions the point of what he sees as the page administrators’ wanton crusade against homelessness.

“[The page] keeps people informed about various public nuisances and crime that goes on in the neighborhood, but it can also be as a bad thing,” Barrett says. “One of the problems many have with the group is that there is a constant bashing of the homeless and mentally ill. The problem with that is, along with those posts, come a barrage of completely insane — may I say ‘hyper-conservative’ — comments from members of the group bashing these people. That, to me, just seems like poor taste.”

Deep Ellum resident Wick Hoover too questions the public shaming he sees in the group and the motive behind it. It’s tough not to, he says. Too often, he says he sees the administrators and most frequent users of the page rushing in to heckle anyone who offers a dissenting opinion to their status quo.

“I live here and don’t disagree with the mission behind the group,” Hoover says. “But sometimes folks on the internet lose sight of real world consequences, so I try to remind them.”

There’s some danger to doing that, though. Administrators are quick to ban users they see as acting against their mission; in turn, they’re determining who is and isn’t privy to seeing the information that they say is meant to be shared in order to keep the neighborhood safe. [Editor’s note: Shortly after interviewing Devries for this story about how this page and others like it affect crime in the neighborhoods they watch, every known contributor to Central Track was blocked from the Deep Ellum Community Watch page.]

Taking such a vindictive stance is not necessarily a new habit for DECW, which does have its fair share of enemies around town. Perhaps its most prominent foe is Yvette Gbalazeh, the “Rap4Weed” lady known for playing her guitar atop the white minivan she would often park at the corner of Elm and Good Latimer while preaching her stoner sermons of marijuana legalization. For months, complaints about Gbalazeh’s presence on this prominent corner of Deep Ellum regularly popped up in the Deep Ellum Community Watch page, with each subsequent post earning more ire than the last. Not just a blight, DECW users argued that Gbalazeh was an especially aggressive panhandler who was quick to get in the face of passersby who weren’t charmed by her pro-marijuana stance. Eventually, police stepped in to remove Gbalazeh and her van from the spot she’d claimed on the street.

During a speech at City Hall in March, Gbalazeh questioned why she’d been targeted by police. In her eyes, she was the one who had been victimized. It wasn’t long after DECW and its users began targeting her as a public annoyance, she says, that the tires on her van were slashed and that she began being harassed more and more frequently by strangers on the street. Gbalazeh even accused DECW users of possibly paying some of her harassers.

To Gbalazeh, there was no doubt as to why she’d been targeted by the group. In her City Hall statement, she alleged that DECW took issue with her because of the color of her skin, and she even went so far as to call DECW a “hate group.”

Every member of DECW was able to watch Gbalazeh make these claims before City Hall — because Devries personally attended the Gbalazeh’s appearance before city council, filmed it and shared it within the community page. Devries says she did this in the name of keeping the DECW page’s users informed on the situation.

“[Gbalazeh] should’ve totally found her niche in Deep Ellum because we are so accepting of one another,” Devries says. “For her to constantly be bucking the system… I really don’t know what her end-objective is. It’s not to blend in with Deep Ellum because she has done everything she can to be rude to business owners and passersby.”

Gbalazeh’s end-objective is hardly a mystery. A 2015 profile on Gbalazeh in the Dallas Observer detailed her efforts in pushing the conversation forward on the implementation on cite-and-release policies for Texas law enforcement agencies when it comes to small amounts of marijuana possession — a measure that Dallas City Council recently approved.

In Deep Ellum Community Watch’s defense, some of its members have very much engaged in efforts outside of a web browser to curb neighborhood crime. Last fall, Devries in particular was instrumental in organizing regular night-time walks of the neighborhood’s busiest streets by the Dallas chapter of the Guardian Angels. And, perhaps spurred on in part by the conversations started by DECW, business owners — many of whom we contacted for comment on this story, although each declined — have been meeting more regularly of late with Dallas Police Department officials to discuss ways in which cops can better patrol the neighborhood.

Those are clear examples of the good that come out of a page like like DECW.

But with plenty of bad — sometimes tasteless pictures that shame the neighborhood’s homeless population; a tendency toward name-calling over conversation and solution-finding; and voyeurs on the page who live outside of the neighborhood and simply take in all of its back-and-forth, leaving with a poor, and perhaps grossly inflated, impression of the neighborhood and its crime rate — the many questions that linger about the page’s greater good seem legitimate, especially when DECW’s administrators rule with such an iron first and don’t seem to think of any of the activity that goes on within their page as particularly problematic.

Devries, for her part, thinks she and her fellow page administrators are handling everything just fine.

“The one and only rule we have is to respect one another’s opinion,” Devries says of how she and her fellow administrators view their role in Deep Ellum Community Watch. “But if an admin does something, we don’t question it. We just let it ride.”