A Look At The City Of Dallas’ Curious Use Of The Video Platform Cameo In Hiring Dallas Mavericks Hero J.J. Barea To Film Pandemic Information Videos.

It’s abundantly clear at this point: Government officials were not prepared for a public health crisis along the lines of the still-ongoing pandemic.

Certainly not here in North Texas, anyway. Here, our officials have alternately Homer Simpson-ed into the hedges and left sight for extended stretches or Spider-Man meme’d one another when seeking to find someone to blame for bungled vaccinaton rollouts.

Overall, the whole scene has been a mess. But just how deep does the disorganization and curious decision-making go? Pretty deep, it turns out! An especially niche example of Dallas’ poorly executed coronavirus response involves Facebook ads, the celebrity video message-commissioning company Cameo and beloved former Dallas Mavericks guard J.J. Barea.

In late November 2020, the City of Dallas began running a series of targeted Facebook ads featuring Cameo-branded videos of Barea talking about the coronavirus pandemic, proper hygiene practices that help prevent its spread and which City of Dallas-run websites residents can visit for more information about it.

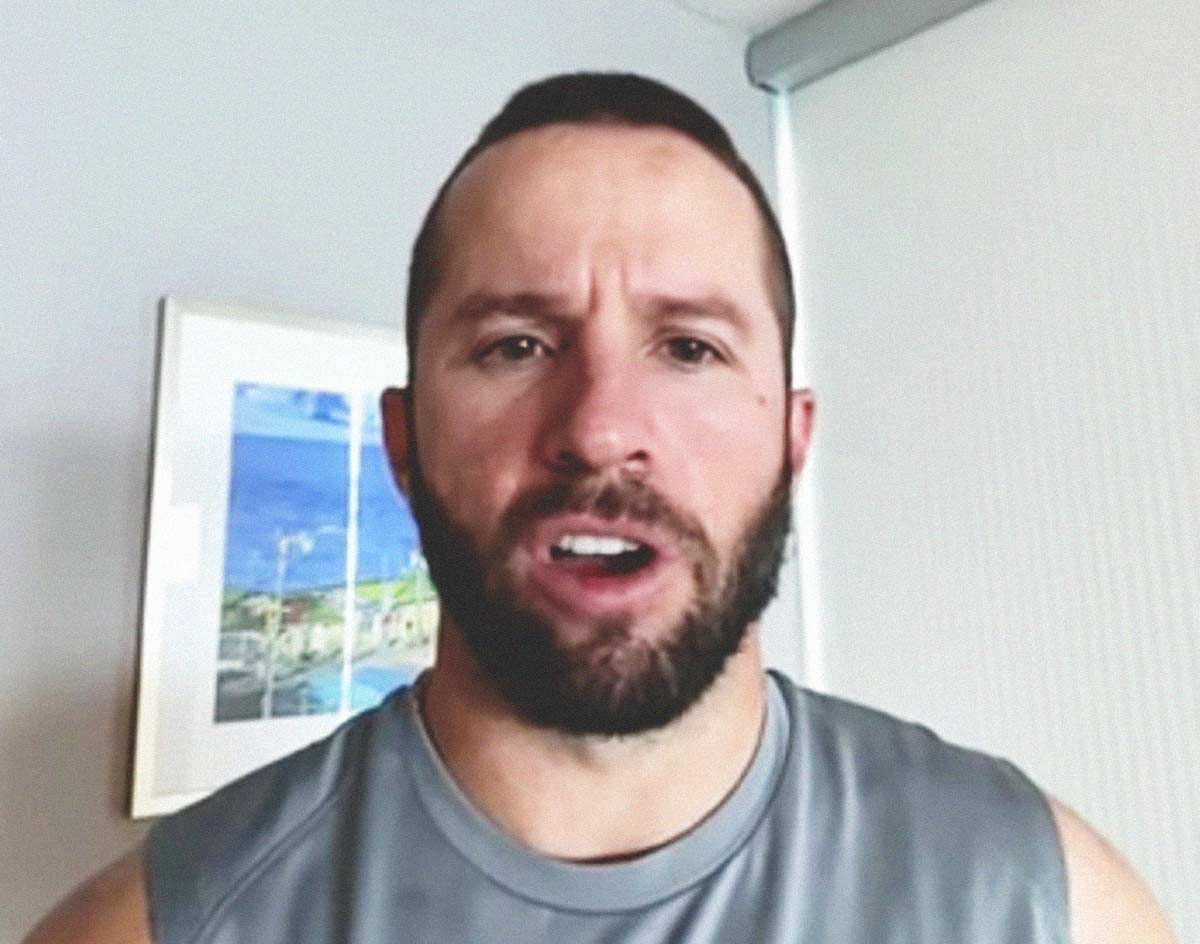

A still from on of J.J. Barea’s Cameo-branded Facebook ads for the City of Dallas.

In all, Barea filmed four short videos for the city — two in English and two in Spanish — that were commissioned from him via Cameo. One of each language was centered around information about wearing masks and practicing safe social distancing protocols, and the other was more focused on intervention options and aid provided by local government services.

Barea has since put a pause on new video requests from his Cameo account, but prior to doing so was charging $99 per video for personal messages to fans, and $5,000 (plus a $250 processing fee) to corporations that submitted commissions. The City of Dallas commissions fell into the latter grouping.

In all, the City of Dallas paid Barea at least $20,000 for the four clips it eventually used — an amount confirmed by Catherine Cuellar, director of communications, outreach and marketing for the City of Dallas.

Cuellar, who herself stars in some additional coronavirus information ads that the city has paid to run on local TV news stations, says the goal of the Barea campaign was to specifically “address Dallas’ Latino community.” She says the resulting footage was targeted through Facebook at people who don’t follow the City of Dallas on social platforms, and that she was “overjoyed” when native Spanish-speaker Barea agreed to take on the commissions — because, unlike professional athletes on the Texas Rangers and the Dallas Cowboys, the organization with which Barea locally made his name actually plays in Dallas.

“We know this virus is disproportionately affecting people of color,” Cuellar says.

Cuellar also notes that not every video request the city made to Barea was accepted by the former Maverick. She says the decision to use Cameo to lure Barea into the campaign was made by one of the city’s contracted agency of record, the Dallas-, Houston- and Mexico City-based company The Voice Society.

The Voice Society partner Leonardo Basterra says his company pursued Barea on Cameo as the service provided a “turn-key” solution to the need because “everything is done online,” and because it offers “access in a timely manner.”

Neither Cuellar nor Basterra would disclose the complete and combined budget spent on Cameos, social media ad campaigns or additional fees, but Basterra says all expenses were agreed upon with his company’s contacts within the City of Dallas.

Both Cuellar and Basterra acknowledge that the inclusion of a Cameo-branded watermark on the video was due to the terms of service included in its commissions.

Cuellar additionally notes that keeping down costs on the city’s public health campaign ad budgets has been difficult this year given advertising rates in the country’s fifth-largest market. The Barea campaign is one of many the city has been underwriting, including others running on Univison and Telemundo that feature FC Dallas soccer players.

Before committing to Cameo as its conduit it to Barea, Cuellar says she initially approached the Dallas Mavericks organization directly to gauge interest in any of the team’s player’s participating in its bilingual social media ad campaigns. The team’s two biggest current stars, Luka Doncic and Kristaps Porzingis, are both fluent in Spanish, but each command at least six figures annually for their endorsement deals these days. After having already participated in a number of city initiatives throughout 2020 — the American Airlines Center served as a polling site in the 2020 general election and also as a COVID-19 testing facility; the team donated PPE to the city; it contributed to a census-awareness campaign; its CEO Cynt Marshall has hosted a number of community meetings to discuss the pandemic. Even the team’s mascot, Champ, is serving as Dallas County’s COVID-19 spokesperson — Cuellar says the organization “politely declined” to offer any shortcuts to its players this time around.

That option cut off at the pass, Cuellar says spending upwards of $20,000 on commissioned videos from Barea was “still the most cost-effective way to get a Spanish speaker [with ties to] the Mavericks organization.”

Over the course of his 14-season career, Barea played 11 seasons for the Mavericks. Prior to his being cut from the team right before the 2021 season’s tipoff, the team signed him to a $2.6 million guaranteed contract — a golden parachute of sorts for the last remaining player in the NBA who had been on the Mavs’ championship 2011 roster.

In late January, the 36-year-old Barea signed a deal with the Madrid-based Estudiantes team in Spain’s top basketbal division. The terms of the deal were not disclosed.

If we had to guess, it was probably less than $2.6 million, but more than $20,000.

Regardless, if his recent appearance on his fellow NBA player J.J. Reddick’s podcast is any indication, he’s living just fine.