A Mysterious Statue Recently Placed Near The Kay Bailey Hutchison Convention Center Suggests Bryan Was More Than Human, Calls Dallas A “Shared Delusion.”

Update at 4:30 p.m. on November 1, 2019: Less than a week after its arrival, the statue depicting Dallas founder John Neely Bryan as a cephalopod has been removed from its perch underneath the Kay Bailey Hutchison Convention Center — although, to be sure, it will remain in our hearts forever.

Original story follows.

* * * * *

John Neely Bryan, the man credited with founding Dallas in 1841, lived a fascinating life. But is it possible that he was also a cephalopod?

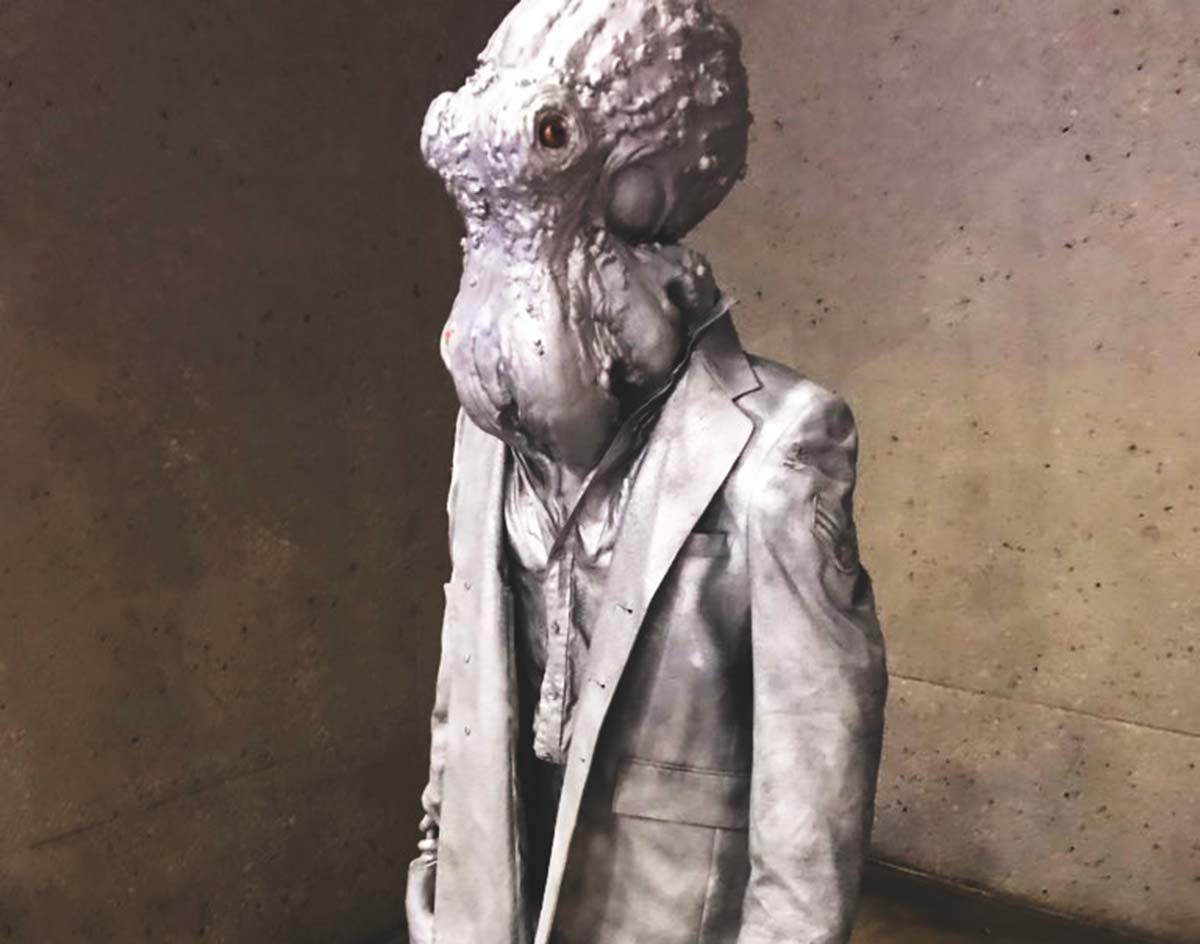

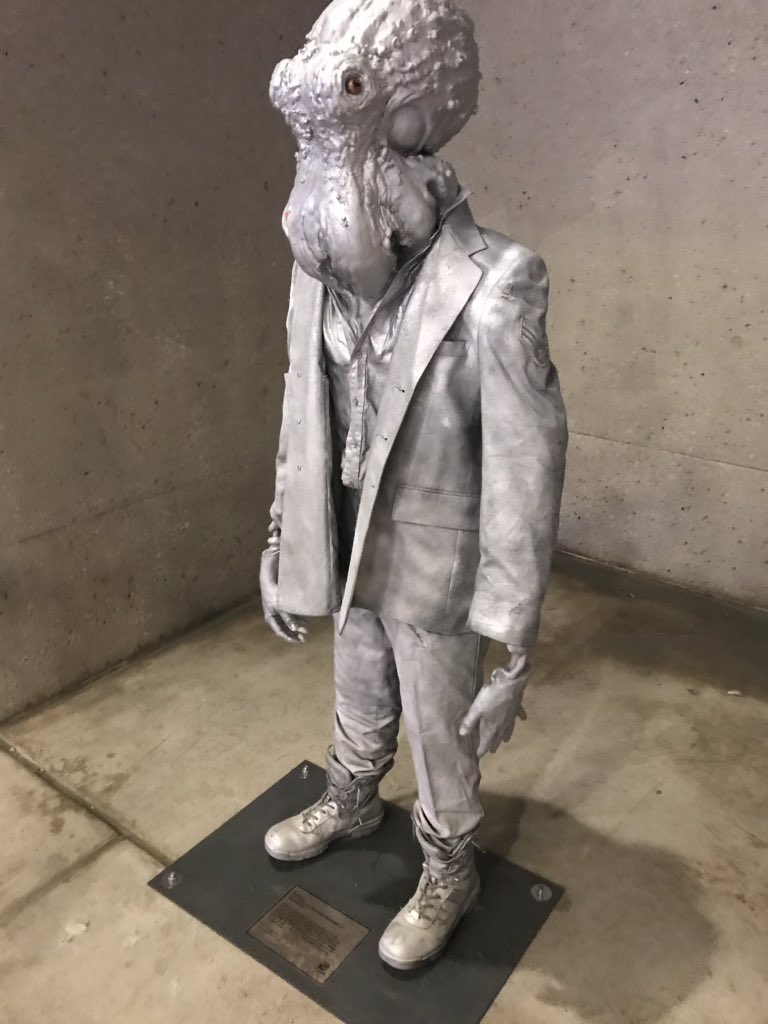

A mysterious new statue that recently appeared in the bowels of the Kay Bailey Hutchison Convention Center suggests just that. Located just a few city blocks away from Downtown Dallas’ replica of his pioneering cabin, this new piece has been installed near one of the DART stops underneath the convention center on the east side of South Lamar Street.

Photo by John Bradley.

After first spotting the piece on his way into work last Friday, Dallas attorney John Bradley shared photos of the statue and its typo-ridden plaque to Twitter this morning when he was surprised to see it still standing after the weekend. He had initially assumed the piece was installed as some sort of marketing play for an event taking place at the convention center, which has been hosting a printing gathering from Wednesday to Friday last week; the fact that it’s still in place now has him convinced it’s “an unsanctioned street art installation.”

It’s certainly something.

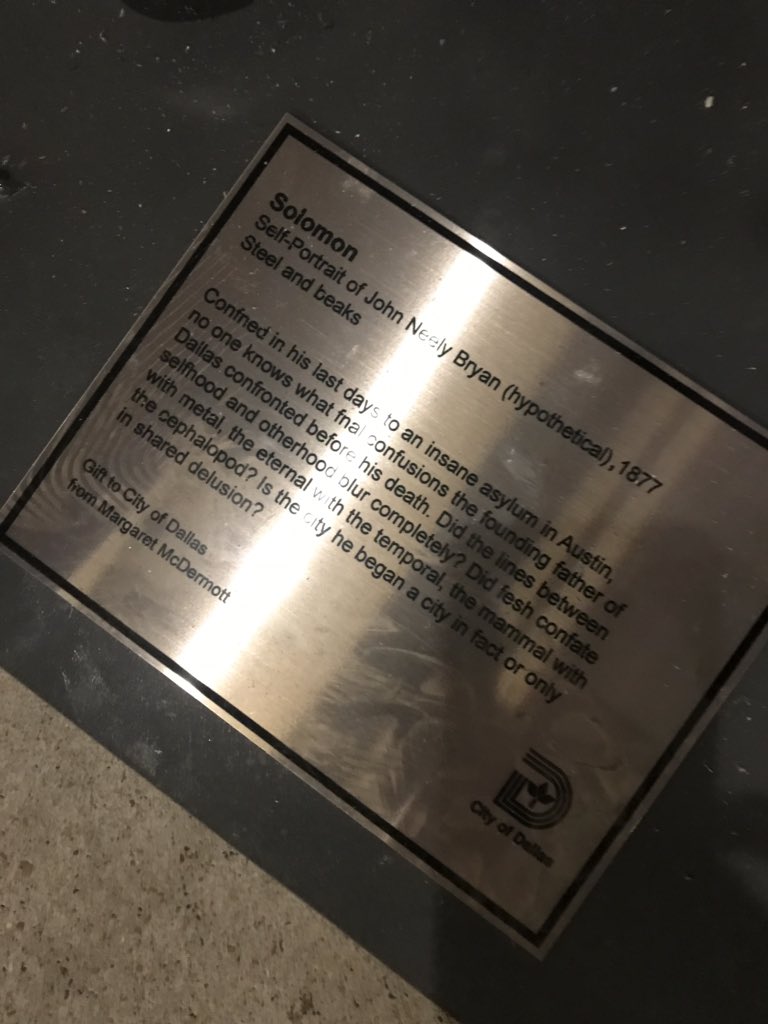

According to its plaque, the piece is called “Solomon: Self-Portrait of John Neely Bryan (hypothetical), 1877” and it is made of “steel and beaks” — an assertion Bradley denies, saying it “appears to not be carved but maybe a model with a real jacket painted to look like a statue.” Also dubious are the plaque’s claims that the piece is a gift to the City of Dallas from the late philanthropist Margaret McDermott, for whom one of Dallas’ Santiago Calatrava-designed bridges was named.

Still, most surprising are the details implied in the (anonymous) artist statement portion of the inscription: “Confined in his last days to an insane asylum in Austin, no one knows what fnal (sic) confusions the founding father of Dallas confronted before his death Did the lines between selfhood and otherhood blur completely? Did fesh (sic) confate with metal, the eternal with the temporal, the mammal with the cephalopod? Is the city he began a city in fact or in shared delusion?”

Photo by John Bradley.

Born and raised in Tennessee, Bryan was indeed many things throughout his life. He was a lawyer and a fur trader, the latter of which brought him to Dallas, where he was the first person to set up permanent residence along the Trinity River. In the city’s infancy, he served as a merchant, a ferry operator and the town’s postmaster, with his home even serving as Dallas’ first courthouse. Later in life he would leave Dallas a few times for years at a time — once to search for gold in California and off to Native American territory in Oklahoma a few years later while ducking the heat after he shot a man who had insulted his wife– but he always returned to the city he conceived, serving it in various civic and ceremonial capacities until 1877, when mental struggles found him committed to — just as the statue suggests — the Texas State Lunatic Asylum, where he spent his final months before passing.

But… a cephalopod? Seems like a reach — but also perhaps a tough argument to disprove. Per Bryan’s Wikipedia page, there’s some dispute over where his remains lie, which would indeed make it tough to find a DNA sample proving that he was 100 percent human.

Makes you think, huh?

Please: If you know anything about how this statue came to be — or if you can prove that Bryan was indeed fully human (or not) — we’d love to hear from you.

Update at 3:15 p.m. on Tuesday, October 29: We reached out to a marine biologist who specializes in cephalopods to see if it was possible that the founder of the City of Dallas was, in fact, a cephalopod. She had some interesting takes on the matter.