The Artists Behind Drifting On A Memory Takes Us Back To The Lowrider Days Of The Twentieth Century, But Those Days Haven’t Quite Left.

Lokey Calderon says he can’t describe the feeling.

“It’s like a tingly feeling – almost like a chill,” he says.

The tattoo and pinstripe artist hits the switch on his shiny, turquoise 1976 Monte Carlo, which he named Disco Lady, and cruises down slowly to ‘70s music – the Golden Age of lowriding. From funk to classic rock of the disco era, Calderon wants his ride to stick to its true identity.

He throws words like “chill,” “free” and “amazing” but it still can’t compare to what riding in one is really like. Lowriders, colorfully customized lower-bodied vintage vehicles, are like mobile art pieces and a form of self-expression – the best thing about lowriding according to Calderon.

“I love to see people’s reactions,” he says remembering the times he’s cruised down the area. “I’ve had people from all walks of life pull up and bend knees to give me thumbs up, talk to me and say how much they love the ride and it feels good. It brings a smile to a lot of people’s faces.”

Now, a glimpse of that experience — a nod to what Lowriding truly represents — is being showcased at the Dallas Museum of Art. A 153-foot wall installation that resembles a lowrider with its pinstripes and vivid colors covers the DMA’s Concourse. This mural of a monumental-scaled ride is the work of Calderon and L.A.-based artist and educator Guadalupe Rosales. The two met through Instagram, bonded over their similar livelihoods and started the collaboration that was initially thought of by Rosales.

Photo by Stephanie Salas-Vega

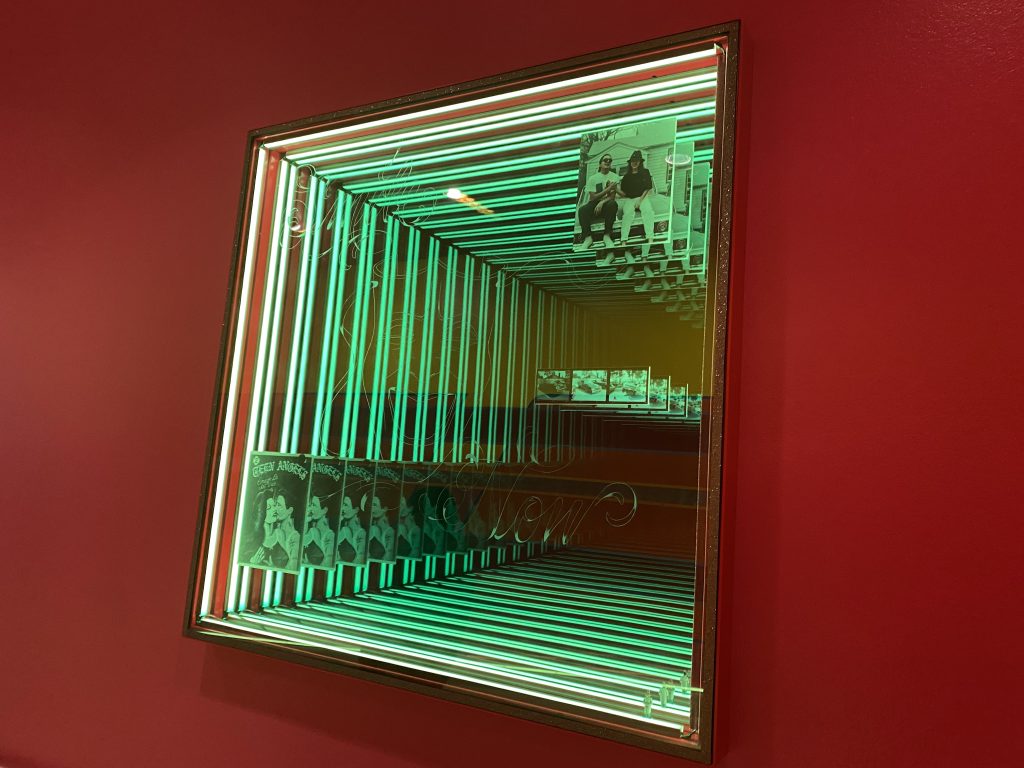

A disco ball sparkles the hand-painted sunset-colored, flaked walls of the Concord and a neon green light strip glows along with it. Above you can see your reflection on what’s supposed to be a big rearview mirror. It’s good for selfies. Rosales created two lightboxes that containing memorabilia such as photographs, Teen Angel art and the iconic Homies figurines. Her idea was to pay homage to the culture that still lingers in Hispanic communities such as her hometown of East L.A. and even Dallas.

Photo by Stephanie Salas-Vega

“The work that I’ve done in the past is about reframing histories,” Rosales said. “I’m mostly interested in celebrating.”

Since 2015, Rosales has documented Latinx experiences with her expansive collection of archives on the Latino underground subcultures in L.A. from the twentieth and early-twenty-first centuries. Her project “Veteranas and Rucas” on Instagram documents throwback photos of kickbacks, shopping mall photoshoots, Sadie Hawkins dances, high school hangouts and girl groups that people submit from their teenage years. Her ongoing project was turned into a book “Map Pointz: A Collective Memory,” which includes newspaper clipping, scrapbook and album pages and an essay.

Lowriding deserved its own praise.

These mobile art pieces aren’t just pretty cars to look at. They’re part of Chicano history and represent the Mexican-American identity, which traces back to post-war urban L.A. During the Chicano Movement in the 1970s, lowriders were more like a formalized political function. Car clubs helped fundraise for the United Farm Workers labor union, it offered community service and hosted health initiatives. Lowriders continue to make appearances in Latinx communities in the south.

Calderon is no stranger to this, in fact, his life has revolved around lowriding and art itself. In one of the lightboxes, a photo of Calderon’s siblings Oscar, who also did the velvet upholstery inside the window box, and Hilda from 1992 sitting on his brother’s ’64 Impala in front of their childhood home near Maple Lawn. The brothers are known as the guys to go to for pinstripe work in Dallas and its been that way for years.

Courtesy of Lokey Calderon

“I pretty much grew up into being that my older brother was into lowriding,” Calderon, who’s 13 years younger than his brother, says. “I was able to witness his early in lowriding and learn from him as he was learning it.”

Inspired by his brother’s art and watching his draw, Calderon followed the art himself. During his middle school years, he helped out at his brother’s shop and was immersed in the lowrider environment. While he takes pride in his culture, lowriding to him was more art-driven than anything.

Courtesy of Dallas Museum of Art

Even though Dallas is no East L.A., the Chicano community and love for lowriding is just as close. Dallas Lowriders, a club that started in 1979, is still around today even after the murder of its leader Ivy Mata in 1985. His brother Mark Mata reunited the club in 2003, the year his daughter Mercedes was born, and has been a spokesperson since and held community-based events that make everyone feel like family.

Now, at 18 years old, Mercedes, also known as Lowrider Girl, is following her in family’s footsteps.

“I was born in this club,” she says. “This isn’t a hobby for us, it’s a way of living.”

Three years ago, she watched her father build a brown 1949 Chevy truck and purple 1965 Super Sport convertible Impala from the ground up and was amazed. Since then she’s dedicated her time to cars, too. Soon, she’ll be sporting her own fully glittered, pink 1984 Chevy Monte Carlo — one that resembles her outgoing and loud personality — that was pinstriped by Calderon, too.

She can agree with Calderon. Cruising down in a lowrider is freeing.

“Just cruising in your ride, hitting switches, left arm hanging out the window, right hand on the steering wheel and your hair flying in the wind,” she says. “I feel like a bird who just learned how to fly.”

Yet, it’s still not the best part.

“The best part is knowing I put my all into my car,” she says.

Drifting on a Memory will be showcased until July 10. The DMA will host a lowrider event March 12 with a car viewing a talk with Rosales and Calderon.

Cover photo courtesy of Dallas Museum of Art on Instagram.