The Dallas Museum of Art’s “Mexico 1900-1950” Is Rightly Earning Props For Showing Works By Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera. But There’s Deeper Meaning Found In Another Piece.

Frida Kahlo’s “Las Dos Fridas” gets all the attention at the Dallas Museum of Art’s “Mexico 1900-1950” exhibit. People are constantly snapping photos of it and setting off an alarm that alerts museum security to when attendees of the exhibit approach that piece a little too closely.

It’s not the most significant piece on display in relation to Mexican culture, though.

Sure, Kahlo’s magnificent self-portrait is stellar exploration of personal duality and bi-nationality — an issue many Mexicans and Mexican-Americans in the U.S. often deal with on a daily basis.

But flying under the radar in another portion of the exhibit is a two-part mural piece that depicts a much more general — but also far grander in scope — story about Mexico and its blending of Aztec and European cultures.

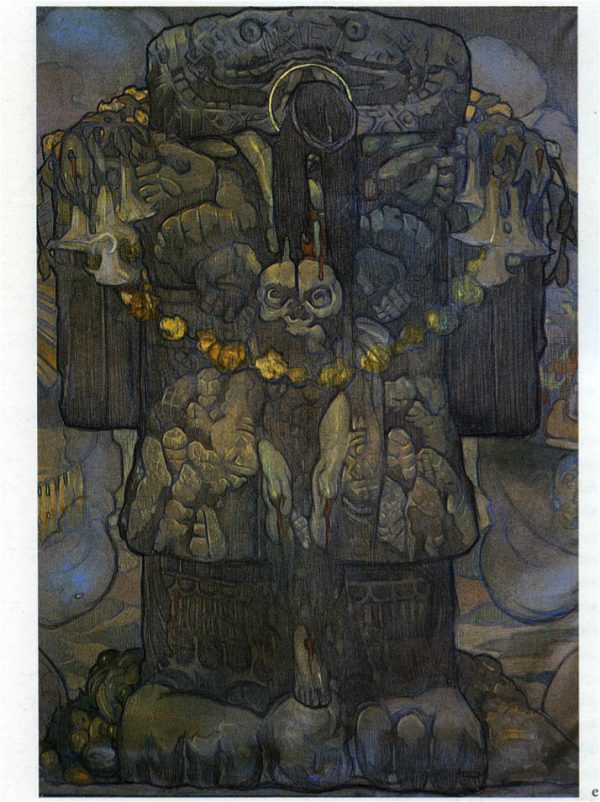

The pieces by Saturnino Herrán are titled “Our Gods,” and they both hang in the first half of the Mexico exhibit. Interestingly, the two Herrán pieces on display are just two-thirds of his entire vision: Originally, “Our Gods” was created as a three-piece project that the artist worked on as part of a contest held by the National Theater (now known as the Palacio de Bellas Artes). He began work on it in 1914. The first piece visitors of the Mexico exhibit will encounter is the mural’s unfinished center panel (pictured above). The charcoal study features a crucified figure on top a statue of Coatlicue, the Aztec deity of death and rebirth.

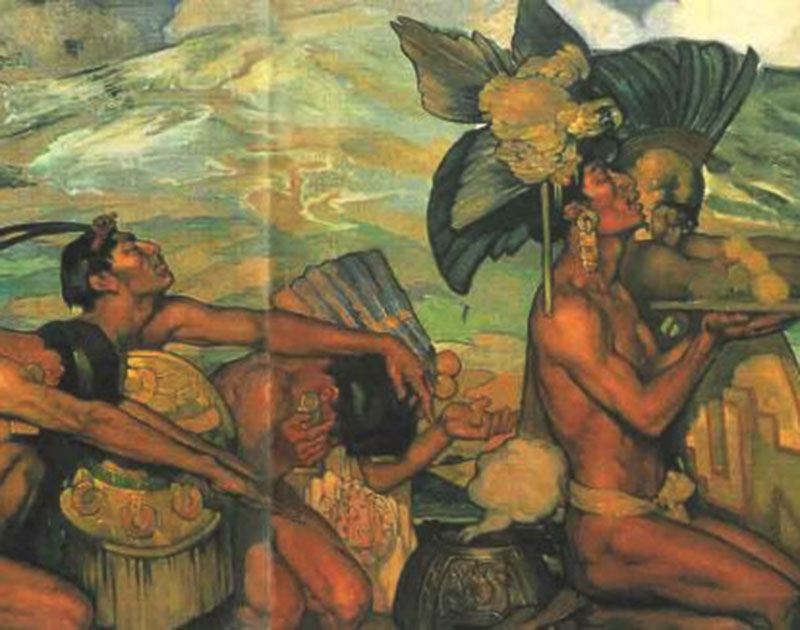

The first piece visitors of the Mexico exhibit will encounter is the mural’s unfinished center panel (pictured above). The charcoal study features a crucified figure on top a statue of Coatlicue, the Aztec deity of death and rebirth. In an adjacent room, the next piece attendees will see is the mural’s fully painted left panel (pictured above), which depicts a group of Aztecs facing to the right, looking toward the Coatlicue figure and offering up a sacrifice in its honor. Of the three pieces in “Our Gods,” it is the only panel that Herrán was able to fully complete before his death in 1918.

In an adjacent room, the next piece attendees will see is the mural’s fully painted left panel (pictured above), which depicts a group of Aztecs facing to the right, looking toward the Coatlicue figure and offering up a sacrifice in its honor. Of the three pieces in “Our Gods,” it is the only panel that Herrán was able to fully complete before his death in 1918.

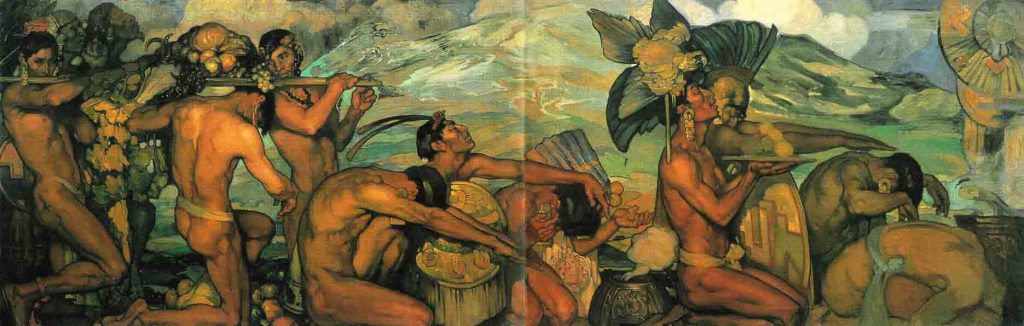

The final piece, and the one missing from the DMA exhibit, is the also-unfinished right panel (pictured above), which is even less far along in its completion than the center one featuring Coatlicue. Little more than an outline for the final piece that was to come, this potion of “Our Gods” depicts a group of Spanish friars, warriors and peasants facing Coatlicue and praying in front of Popocatépetl, an active volcano in Mexico.

The final piece, and the one missing from the DMA exhibit, is the also-unfinished right panel (pictured above), which is even less far along in its completion than the center one featuring Coatlicue. Little more than an outline for the final piece that was to come, this potion of “Our Gods” depicts a group of Spanish friars, warriors and peasants facing Coatlicue and praying in front of Popocatépetl, an active volcano in Mexico.

That third panel, it’s safe to say, brings the piece full circle and makes clear the sheer scope of Herrán’s intended work, which covered the trajectory of indigenous faith up until the point when Mexico was colonized by Spain beginning in the 1500s. With this piece considered, “Our Gods” becomes a powerful representation of how Mexican faith came to be as it is today, as some 88 percent of Mexicans adhere to the Roman Catholic faith and another seven percent follow some form of Protestant Christian faith. Despite their religious affiliations, most Mexicans will mention how proud they are of their Aztec heritage, which, whether they acknowledge it, is one very much grounded in the indigenous faith of Mexico’s past. Images of Aztec gods have, of course, persisted in Mexico in all walks of life through the centuries.

On some levels, it’s a shame that the DMA was not able to procure this final piece, as the perspective it adds to the greater picture is massive. But, armed with the knowledge that this third portion exists and that it depicts what it does, viewings of the two “Our Gods” panels in the DMA’s possession are undeniably heightened. Particularly to exhibit attendees of Mexican heritage, “Our Gods” is a stunning insight into not just Mexico’s past, but also that of Central America’s and North America’s at large. It’s near impossible not to be swept up in the story it shares, to be emotionally consumed by its blunt honesty.

Then again, maybe the fact that the DMA’s exhibit does not boast the right panel of “Our Gods” is perfectly fitting. That a significant portion of a painting that aims to recreate the entire history of Mexico is both incomplete and missing from this showing is chillingly analogous to the way in which the Mexican people at large oftentimes gloss over entire sections of their country’s vast history. To be reminded of the forgotten past, however, is to gain insight into how things came to be as they are today. That’s an important thing to consider both when viewing the history of a nation such as Mexico, but also when viewing “Our Gods” as it is on display at the DMA.

Kahlo’s self-portrait may be the one literally setting off alarms at the DMA, but Herrán’s ambitious “Our Gods” is the piece that may end up stirring more within its viewers. While both pieces deal in duality, Kahlo’s focuses on an inner, personal struggle as Herrán’s attempts to captured that of an entire people.

It, like Mexico’s contributions to North America, isn’t to be ignored.

“Mexico 1900-1950” runs through July 16 at the Dallas Museum of Art. Head here for more information.