An Investigation Into The Weapons Dallas-Area Law Enforcement Agencies Used To Control Crowds At The Start Of The City’s 2020 Police Brutality Protests.

All photos by Shane McCormick.

More than three weeks have passed since protests against police brutality and systemic racism — sparked by the death of George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis police — broke out across Dallas.

Since the mass detainment of protesters on the Margaret Hunt Hill Bridge on Monday, June 1, these daily rallies and marches have continued on and been mostly non-confrontational; peaceful yet passionate, though still anything but tranquil.

In the last few weeks, groups of protesters have started taking their efforts off the streets and into the private sphere by walking through a Whole Foods in North Dallas and a Target in Uptown, and without a single incident of theft or vandalism. Police cruisers and motorcycles, meanwhile, have ceased closing in on or marking march routes — implicitly acknowledging that crowds can safely handle traffic while guiding themselves.

Police and protesters now seem almost to be ignoring one another. But few have forgotten the brutality and trauma experience throughout the first four days of demonstrations.

“It looked like fucking Baghdad,” one protester remarked while recalling the last Saturday in May, the second day of demonstrations.

Here’s a refresher of how shit went down within those first four days, and just how squarely it hit the fan.

- On Friday, May 29, activist Dominique Alexander’s Next Generation Action Network led a march from the Dallas Police Department’s headquarters in the Cedars towards Downtown Dallas with an unknown destination; within an hour, the march had morphed into a scuffle with police. A few protesters hurled water bottles and stones at police officers; others smashed and spray-painted police cars. Patrolmen and SWAT responded with tear gas canisters, flash bangs and foam-tipped plastic 40-mm rounds; quickly and forcefully, they dispersed the crowd, only for it to regather a bit later.

- At around midnight on that first Friday, the situation deteriorated further. Following the initial clashes with police, individuals intent primarily on burning and smashing — lured downtown by the earlier back-and-forth being broadcast live on local TV — crawled Downtown Dallas’ streets. They looted Neiman Marcus, Traffic and Forty Five Ten, set dumpster fires, built barricades in the streets, broke out in fistfights and burned at least one police cruiser. The police responded by indiscriminately firing tear gas and projectiles. The ugly situation continued well on into early Saturday morning.

Y’all stay safe out there

Caught this from @Central_Track #dallasprotest pic.twitter.com/zY317qSZyR

— Dirty Diaz (@zaidnaitsirhc) May 30, 2020

- Following Friday’s clashes, hundreds of protesters descended upon Dallas City Hall on Saturday — and twice marched through the Downtown Dallas streets without incident. These protesters came prepared for a repeat of the previous night’s events; many carried tear gas neutralizing agents in their backpacks, but most were without any hard hats, goggles or gloves necessary to shield them from high-speed projectiles. Police too came out ready, both in terms of volume and armature; a coalition of Dallas, Arlington, Garland and Irving police officers assembled alongside Texas Department of Public Safety state troopers in the name of crowd control.

- After marchers returned to City Hall Plaza for the second time on Saturday afternoon, tensions escalated quickly. As protesters flooded around the flagpoles at the intersection of Young and Akard, police drove a caravan of cars onto Young Street, effectively splitting the peaceful protesters in two groups. As they left their squad cars unattended and unguarded, they began to push the crowds out of the street. In response to that show of force, some protesters threw rocks and water bottles at the cluster of deserted cruisers and suburbans, whose sirens continued to blare. At least two masked individuals smashed police car windows, even as others in the vicinity called for them to stop. While using their riot shields to push the masses back, police then began shooting pepper balls at the ground in front of the crowd, hitting at least a few protesters in the legs with batons and macing at least one woman in the face. After donning masks, they began to launch tear gas in both directions — toward one group on City Hall Plaza, and at another faction on Akard street.

https://www.instagram.com/p/CA1BfSZBFmw/

- After this initial conflict, the situation devolved further, increasingly resembling asymmetric urban warfare while spreading chaotically through Downtown Dallas and the surrounding neighborhoods throughout the rest of the afternoon and night. Amidst a repeating cycle of police approaching and gassing groups of protesters, opportunists once again started smashing cars and looting businesses in Downtown, Uptown and Deep Ellum. At least one vigilante ran through the streets with a machete, seeking to protect his favorite bar (and ending up in the hospital). Law enforcement officials allegedly deployed almost every imaginable “less-lethal” projectile: rubber bullets, wooden pellets, foam baton rounds, foam-tipped plastic 40-mm rounds, tear gas canisters, tear gas grenades and flash bangs. As the day stretched on, more and more law enforcement units were called in to aid in the response, including members of the Irving Tactical Unit, numerous Dallas SWAT units and at least one DPS Special Response Team represented by Texas Rangers. That final team was fully militarized: Driving unmarked olive mine-resistant vehicles, they were equipped with olive fatigues and a full battle regalia of body armor, rifles or shotguns and headphones; per their own description, they are “trained to conduct high risk warrant service and provide initial response to critical incidents involving barricaded subjects, hostage situations, and active shooter incidents,” although no such scenario existed on this Saturday.

- Sunday was notably different — mostly quiet except for a peaceful vigil held at the Freedman African Memorial Cemetery. Still, after announcing a 7 p.m. curfew for Downtown Dallas and its surrounding neighborhood just that afternoon, police used Dallas Area Rapid Transit buses to round up violators en masse starting at 7:05 p.m.

- On Monday, June 1, Alexander’s NGAN group led another march — this time from the Frank Crowley Criminal Courts Building just outside of the curfew zone, and again with an uncertain path. By now, you know this story. More than 700 peaceful protesters — high school and college students, young and elderly adults — walked onto the Margaret Hunt Hill Bridge, where the lights were shut off and Dallas police officers (along with DPS state troopers) kettled them in. When the protesters fell to their knees and raised their hands — shouting and chanting “Hands up! Don’t shoot!” and “No violence!” — officers fired metal gas canisters along with foam-tipped bullets in their direction. Their fire hit at least one girl in the head, causing her blood to splatter onto the pavement as medically experienced protesters gave her butterfly sutures and awaited an ambulance that took more than an hour to arrive. (While filming the march and wearing clear “PRESS” identifiers on his person, Steven Monacelli, one of the authors of this piece, was hit with at least two different projectiles, including a green-paint marker round. He was also engulfed in smoke that he believes to be tear gas.)

- In total, 674 protesters were arrested on the bridge under under a wide range of possible but mostly unspecified charges, where some were detained for as many as four hours with no real instruction about what fate awaited them. Three days later, all charges against these parties would be dropped.

Even three weeks after those four days of terror, it’s clear now that local law enforcement agencies failed to coordinate within their own jurisdictions, let alone across departments, during this stretch — just as they have continued to do after the fact.

These officers were caught firing weapons into crowds with impunity (not to mention cheers and songs), but, amid increasing calls for her resignation, Dallas Police Chief Renee Hall — despite personally signing off on the use of tear gas heading into the protests — has still yet to confirm whether, let alone how, her department used the “less-lethal” ammo at their disposal.

The closest Dallas leadership has come to acknowledging its police force’s appalling actions is its city attorneys accepting a court-ordered injunction banning the use of tear gas and “less lethal” bullets for a 90-day period.

That Dallas didn’t see worse injuries and more damage over those first four days of conflict is nothing short of a miracle.

But why did things even get to this point? Which law enforcement agencies fired what types of projectiles? When did police decide to use the weapons beyond the service and assault weapons also on their persons? What perceived threat prompted the use of these “less lethal” options, specifically? Did officers attempt employing other, less drastic solutions or remedies first? If so, for how long?

We’ve heard a lot of misinformation about what happened in those first few days, which weapons were used and to what effect they were employed — mostly from city officials, and then parroted by some in the local media.

Let’s clear the air.

“Sponges” (And Other Projectiles)

Vincent Doyle, who sustained a broken cheek from a police-fired projectile, believes that a “sponge round” hit him on Saturday, May 30. He recalls a laser beaming into his eye as he backed away from an advancing police line while yelling “Don’t shoot!” Then: Pop! In a video he posted on TikTok, he can be seen doubling over, heaving, with blood streaming through his hands.

Brandon Saenz was shot in the eye earlier on Saturday, and he too believes he knows what hit him. WFAA reports that “officers in photos provided to Saenz’s attorneys by witnesses at the scene that day are holding yellow rifles that fire a 40-mm ‘sponge round’ meant to repel someone, but not maim them.”

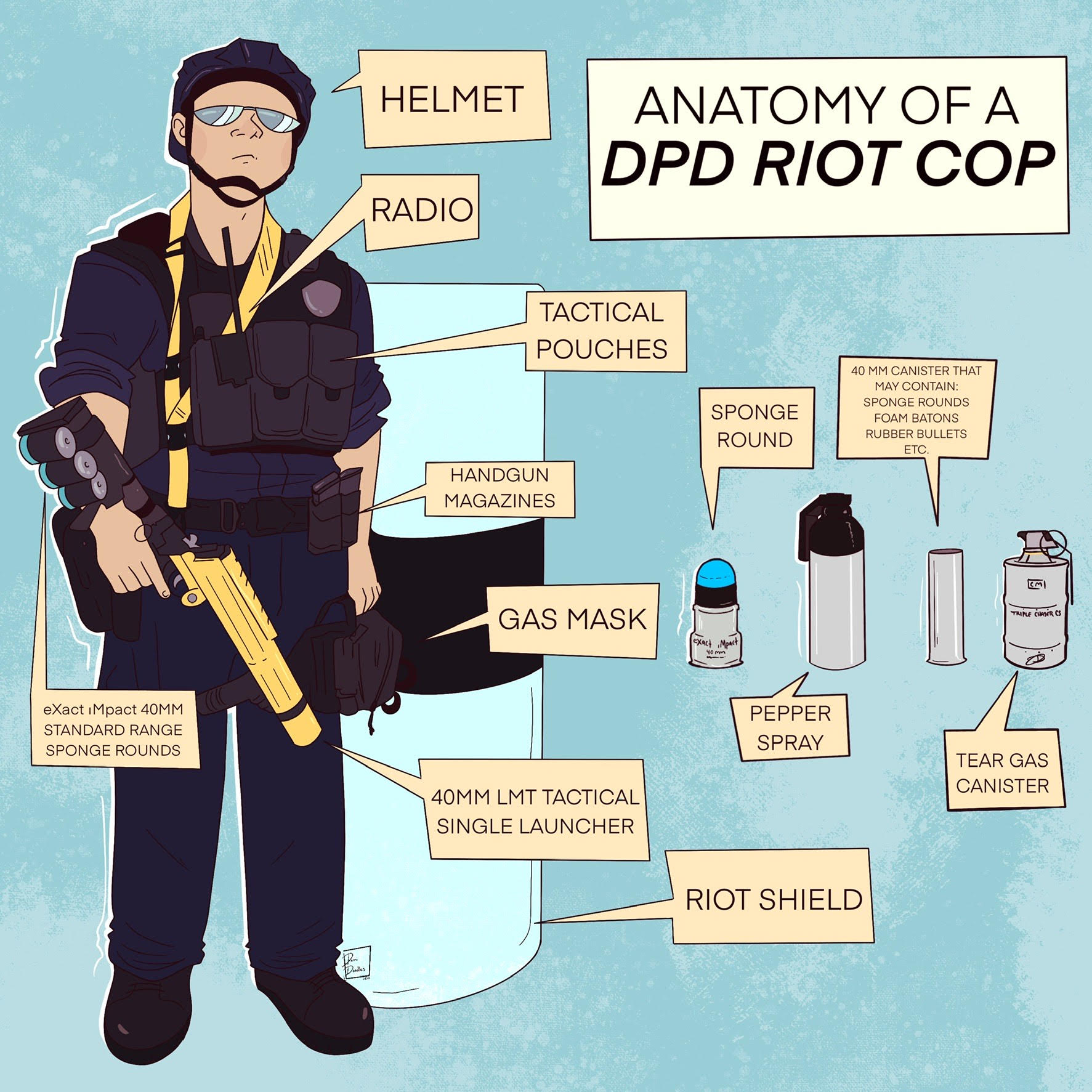

That all is consistent with the information provided D Magazine by the president of the Dallas Police Association, Mike Mata, who explains that Dallas police officers use the 40-mm LMT Tactical Single Launcher — a canister grenade launcher, essentially — to fire the eXact iMpact 40-mm Standard Range Sponge Round. (CBS 11 reported in 2016 on DPD’s $225,000 acquisition of these “sponge guns” for crowd and riot control.)

Illustration by Demetria Hodges.

Despite the soft “sponge” name, these rounds are essentially plastic with a foam nose. The launcher and projectile alike are manufactured by Defense Technology, which is itself a subsidiary of Safariland, a United States-based weapons manufacturer tied to the use of tear gas in Puerto Rico and on the Texas-Mexico border.

DPD’s other crowd-control weapon of choice is the FTC — a paintball gun designed to fire pepperballs. Both the gun and projectile are manufactured by the eponymous company PepperBall.

Defense Technology’s 40-mm LMT Tactical Single Launcher can also fire more than foam-tipped plastic rounds–and, throughout those four days of terror, Dallas police officers utilized its capabilities to their maximum potential. We reviewed video footage of a Dallas SWAT officer using the LMT Tactical Single Launcher to fire into the crowd with a 40-mm Direct Impact Adjustable Range Round OC, whose orange tip is loaded with pepper spray powder.

On Sunday, May 31, freelance photojournalist Jordan Smith found a 40-mm Multiple Foam Baton Round cartridge, which, when fired, releases three foam cylinders and is used, according to its own description, “in riot situations where police lines and protestors are in close proximity.”

Smith also found both 32- and 60-caliber rubber bullets that can be loaded into 40-mm cartridges. Smith and multiple Central Track contributors (including one of this piece’s authors, Trace Miller) found canisters from the Triple-Chaser Separating Canister CS, which releases tear gas.

Each of the aforementioned rounds, canisters and cartridges we found were manufactured by Defense Technology and can be fired from the 40-mm LMT Tactical Single Launcher.

Our assessment was made by processes of deduction and induction, by comparing the size of the projectiles, the sounds made by weapons discharged in videos and the sizes of bruises or wounds sustained by protesters.

Tear Gas-Lighting

Chief Hall has been careful not to confirm her department’s use of tear gas in public statement.

But she seems too intentionally focused on semantics — and, specifically, on the differences between OC, CS and CN gas, even if her efforts may be in vain.

OC is pepper spray — literally. It is made with oleoresin capsicum, which is derived from peppers such as cayenne.

CS and CN, on the other hand, qualify as tear gas — the chemical compounds chlorobenzalmalononitrile and chloroacetophenone, respectively.

Tear gas canister found by Central Track photographer Shane McCormick. Photo by Pete Freedman.

The vast majority of tear gas canisters we found were manufactured by Defense Technology and dispersed CS gas.

Some could have been launched from the 40-mm LMT Tactical Single Launcher; others were simply thrown by hand.

Smith did find one canister manufactured by Combined Systems that dispersed CN. According to Medscape, CN — which Defense Technology describes as five times stronger than CS — can cause permanent skin damage, corneal epithelial damage and chemosis. The same Medscape article cites CN as responsible for five deaths “due to pulmonary injury and/or asphyxia.” Ironically, Defense Technology describes CS gas as ten times more “effective” than CN, even if less toxic. The key takeaway here: The intended effect of CS and CN is exactly the same, even if the chemical compounds (and their respective properties and reactions) vary; partly chemical in nature, marketing makes up the biggest differences. (Think Diet Tear Gas, Tear Gas Light, Tear Gas Zero and so on.)

It’s important to note, too, that these weapons, projectiles and chemicals, all of which are used for crowd and riot control, do not relate to the controversial 1033 Program that is often responsible for the militarization of police. The 1033 Program allows law enforcement agencies to acquire outdated or unwanted Department of Defense equipment. For example, between October 2013 and May 2014, the DPS acquired four mine-resistant vehicles (MRAPs) — originally valued at $733,000, according to the Defense Logistics Agency — for the Texas Rangers, its special ops division. Between May 1994 and October 2011, the DPS Aircraft Operations, which is responsible for DPS’ airplanes and helicopters, acquired an additional 25 7.62-mm rifles (the same caliber as an AK-47). In February 2003, Dallas County Hospital District Police Department acquired seven 7.62-mm rifles of its own, while the Dallas County Sheriff’s Office acquired around 25, plus another 40 or so 5.56-mm rifles (the same caliber as an M16). Notably, the Garland, Arlington and Irving police departments do not participate in the 1033 Program — and neither does DPD, as Laurie Patterson, a program specialist for the Texas Law Enforcement Support Office (1033 Program), confirms.

All these technical terms are a little confusing, no? By refusing to confirm whether tear gas was used on the Margaret Hunt Hill Bridge — in the face of overwhelming anecdotal evidence heavily suggesting as much — Chief Hall either is willfully embracing the public confusion over the difference in OC, CS and CN gas, is ignorant of the differences herself or is hoping that her continued delay in answering will afford her department the time to finger one of the other agencies working in tandem with hers for their actual deployment.

Whatever the case, gas usage seems all too quick a resort for Dallas law enforcement — and one perhaps relied upon more than we even know.

At the Dallas Alliance against Racist and Political Repression protest held on Saturday, June 6, at Belo Garden, rally organizer Jennifer Miller accused DPD of employing gas at a 2018 protest against police brutality sparked by the death of Botham Jean.

If true, that accusation undermines the widely spread DPD claim that its department hasn’t used tear gas in approximately 30 years.

Who Is Being Protected Here?

Bearing all this in mind — the proliferation of expensive and dangerous armaments acquired by law enforcement agencies, and their irresponsible usage leading to severe injuries and near-deaths of civilians — is there any way to justify any usage at all of “less lethal” weapons by law enforcement agencies?

“We definitely need those less lethal weapons,” says DPD Cpl. Larry Bankston Jr. “They’re used to save lives. If some officers don’t have options, that could send us right back where we are now.”

In very specific and rare circumstances, yes, this ammunition can be used to save lives; or, less charitably speaking, to reduce the damage doled out by officers protecting themselves from a perceived threat.

In 2017, police in Madison, Wisconsin, used a 40-mm launcher to subdue a man seeking “suicide by cop.” In 2018, police in Spokane, Washington, reportedly used the Defense Technology 40-mm LMT Tactical Single Launcher and the eXact iMpact 40-mm Standard Range Sponge Round to subdue a man in a similar situation.

It must be conceded, too, that these weapons are, as their name claims, “less lethal” than a standard lead bullet fired by a standard handgun or rifle. In limited circumstances and situations, these “less lethal” weapons and rounds may, in fact, be appropriately used.

But is there any way to justify shooting Doyle — an unarmed photographer in a public parking lot who was retreating from the police — in the face, after aiming at him with a laser sight, whether the round is nonlethal, “less lethal” or more traditionally lethal?

What is an appropriate police response to the perceived threat of a crime? What situation does merit a police response involving “less lethal” force?

Per DPD’s recent activity, all it takes is a thrown plastic or glass bottle — or perhaps a rock or brick — in the direction of a police officer. If it’s a handful of people, they’ll get a projectile; if there’s a crowd, tear gas.

That’s just the reality. But is such a police response merited? Or justified? Or even justifiable?

Should our police be attempting to anticipate and prevent crime via precognition? Are we asking that they anticipate crime before it occurs, and prevent it with prejudicial force? At what point do they start employing other forms of aid — ones that involve less-heavily armed and more-heavily educated responses?

For her part, Chief Hall has repeatedly emphasized the number of police cars that her department lost in the protests on Friday and Saturday as justification for her officers’ response. (See above video).

She has also pointed to the number of protesters throwing bricks at her officers as an explanation — only to reply, when pressed on how many bricks were thrown, that she “wasn’t counting.”

Perhaps in her defense, she also maintains that she doesn’t yet know how many tear gas canisters, “less lethal” projectiles and other riot control devices were employed in law enforcement’s efforts to disperse protesters.

But if her own anecdotal evidence can be used to justify her police’s heightened response to protesters, then surely the information laid out in our investigation is enough to confirm what Hall still hasn’t: However you choose to look at the first four days of unrest here in Dallas, the police’s response to it was more than objectively aggressive; their actions willfully put Dallas citizens directly in harm’s way.