Sean Starr's Studio Is A Blast From The Past.

Welcome to Space Invaded, a new recurring feature in which we peer into the desirable workspaces of various Dallas creatives and try keep our envy to a minimum.

Before the rise of graphic design and what we now know as branding, there was sign painting. The need for merchants to be able to properly direct people to their goods and services gave rise to the world's second oldest profession — at least that's how Sean Starr tends to see it.

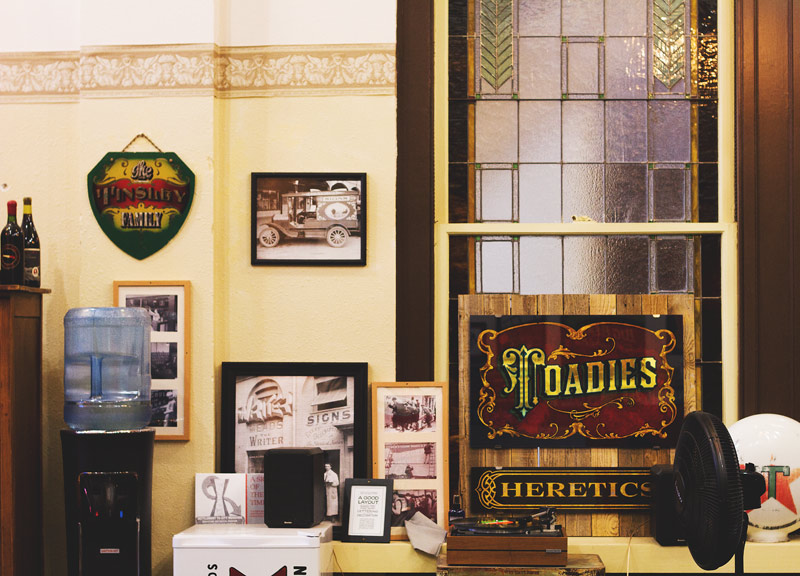

The name Sean Starr or his Starr Studios may not necessarily ring a bell, but his brand of traditionally hand-painted signs can be found all over, from national campaigns, to restaurant signage all across the Metroplex, and even in the form of logos and album artwork for bands like the Toadies, and custom paint jobs on motorcycles and other forms of transportation. In fact, custom work is where Starr got his start, as he entered the paint world doing business with his father's company, Starr Custom Paint in San Antonio in the 1980s.

“Getting started in the hotrod scene, and pinstriping — my dad took that with him, because he used to drag cars up in Cleveland, and my uncles and all of them used to drag race,” says Starr about his automotive beginnings. “Cars are huge [there]; everybody worked for the car industry, and everybody was really into their cars. He brought that culture into the family, and I've been passionate about cars and motorcycles since I was a little kid, because that was what we grew up around.”

After his father passed, Starr took a job in Seattle doing digital and vinyl signage, then relocated to San Francisco to start Starr Studios. But it was a cross-country road trip in 2007 that brought him to North Texas, where he's set up shop ever since.

“I stopped to visit my sisters that live in Denton, and I stayed,” Starr laughs.

While he considers Denton his main base of operations and has plans for an artist residency in Dallas, it's his workspace out in Denison that drew our attention.

Nestled in a town virtually untouched by time, and almost more Oklahoma than Texas, lies an old-fashioned train station that currently houses Starr Studios. At first blush, the brick building seems unoccupied, except for possible apparitions. A trip down the hallowed halls reveals a room inundated with signs that could only belong to his shop, but that was the station's dining hall over 100 years prior. Sure, it seems like an unusual place for a painting studio, but the building is owned and occupied by a sculptor, who gave Starr the opportunity for the space.

Says Starr: “[My wife and I] were driving around the town, kicking around the idea, and saw a for lease sign on the building, then decided to just give it a call. When [the owner and I] started talking, I hit it off with him, and I thought it was a good fit.”

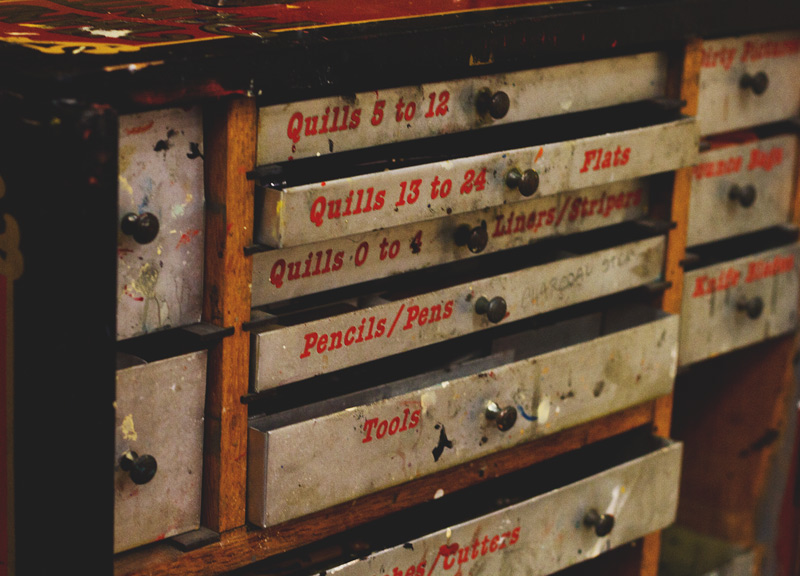

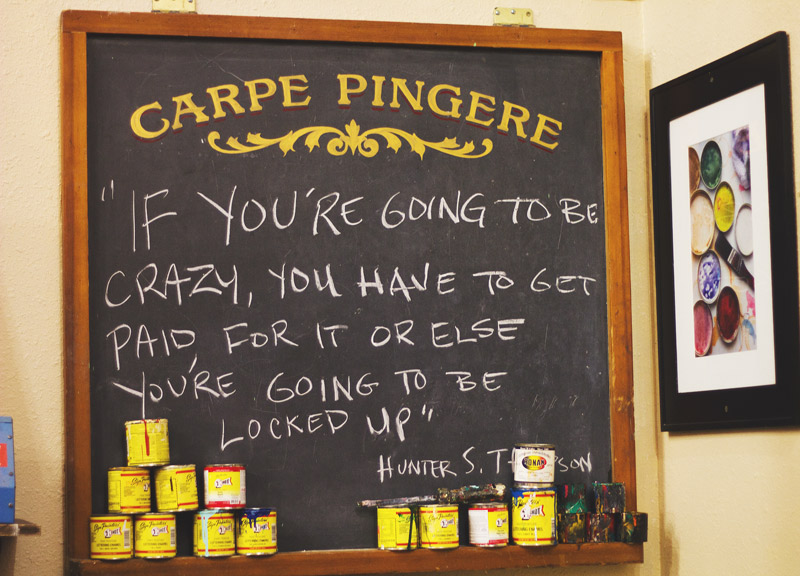

The room seems smalls for his caliber of work, but wheeled tables give the space added functionality, and its secluded location allows him to record his podcast, Coffee With a Sign Painter, without distraction. Signs from past projects adorn the walls, with paint splattered surfaces below. A curio cabinet holds sign painting artifacts Starr has collected over the years while his desk acts as the display for his other collection — an abundance of pencils.

The shop has all the intricacy you'd expect from someone who works primarily with his hands. This is why we were interested in getting to know a little more about his creative process.

Would you say that being in this old, historic space has influenced your creative process at all?

Yeah, it for sure has. I've always been drawn to the historical things, and it's a huge part of our work, which is one of the reasons we were drawn to look into the space. It really allowed me to pursue some other things while we were here, including starting our podcast. We kind of got into such a fast-paced routine when we were in Denton, doing work all over Dallas and Fort Worth, that I kind of needed to slow things down for a bit. And that allowed me to develop the podcast, and develop more of the glasswork that we do with gold leaf and mirroring.

Working with your father in the painting industry, did you ever feel like it was something that would carry over into your life?

It was just so synonymous with everyday life that I never thought about it. It was normal for us, and I imagine it wasn't normal for most other kids. But for us, cars and motorcycle stuff were always just part of daily life.

Was custom work the majority of the client base?

Yeah. When [my dad] started Starr Custom Paint, we exclusively did custom paint on vehicles. We ended up doing airplanes and buses — we did Willie Nelson's tour bus years ago. As time went on, we got more and more requests to incorporate lettering into the custom paint, and pinstriping work. I was really passionate about that, and started down that trail, then started working in sign shops after he passed away.

Being in the painting industry for so long, what would you say are your ideal conditions for a work space?

Air conditioning is a big plus [laughs]. I've worked in just about every environment you can imagine, between here, Seattle, San Francisco and L.A. For me, good lighting is important, music is important and air conditioning and heat.

Do you mostly listen to vinyl, as far as music goes?

That's a fairly new venture for me. I'm old enough that I grew up on vinyl, but I listen to a lot of really old stuff. I love old western swing. I love old jazz. From growing up in San Antonio, I actually like a lot of conjunto music, like Flaco Jiménez. So for me, it's kind of cool having getting back into vinyl, because I can find stuff that's not digitally available.

It's kind of funny. You can tell I'm a little younger, but most of the people my age are more into vinyl than they are into these digital outlets.

I'm late to the game. I know there's like this whole hipster thing with vinyl, and people are fanatical. You know, I actually traded for that [record player]. I did some gold leaf work on a Dallas designer's helmet and motorcycle. He'd just had that rebuilt, and we were already talking about records, so I just swapped him for that. I think it's really cool. It's allowing me to go back and find stuff that I knew years ago, but definitely can't find on iTunes.

Are there ever any times that you paint specific things, based off of what you listen to that day?

Yeah, it's funny you mention that. I just did this helmet that's going to be used in Baja in November, when they do the big run. I also do a lot of work for a place called Rusty Taco, and whenever I do that kind of stuff, I end up listening to Mexican music, Tex-Mex music. Some of the more detailed stuff, I find myself listening to old Charlie Parker. It's a huge influence. I talk about it all the time on the podcast, because that's one of the questions I ask everyone I interview, is what's on your iTunes this week. For every sign painter, artist and designer I've ever talked to, music is as big a part of the process as anything else.

I think people underestimate how hard it is to work in silence sometimes.

A lot of this type of work is very solitary. You're alone for hours on end, working on stuff. Maybe music is the company that you get.

I spoke with Michael Wyatt of Full City Rooster about the festival in Limerick you guys are doing this month. How did the opportunity with The Cranberries come about?

There's a sign painter in Ireland named Tom Collins, and I interviewed him on the podcast early on — he was like the fifth or sixth interview I did. We just really, really hit it off. Like immediately, we were on the same page on so many things, and really bonded. So we started doing a lot of conversations on Skype, talking about business and stuff. About a month after I first interviewed him, he contacted me and said, “Can I share your contact info with our tourist board?” and I said OK. Then they contacted me, and said, “If we flew you and your wife out, would you guys come to our arts festival? We wanna screen the movie Sign Painters, and have you do a Q&A afterward,” because we were in that film. And I was like, “Duh.”

Were you a fan of The Cranberries before then?

I was huge into The Cranberries. I'm a huge Smiths and Morrissey fan, so right around the time that Morrissey split off and started doing solo, that's right around the same time that The Cranberries came in. And to me, I still love Morrissey, but they were kind of like a surrogate, because they were still a band and they still had that vibe.

Do you have a favorite song by them?

I think “Free To Decide” is for sure my favorite. It's got a lot of personal layers to it.

You mentioned painting Willie Nelson's tour bus way back when. What are some of the weird, or most interesting projects that you've worked on over the years?

The oddest, in recent years, was working on three taco trucks for The Gap. It was conceptually so weird, but very cool. There's a design firm up in Portland, called Official Manufacturing Company. They brought us on board initially; we started doing some stores in L.A. for The Gap. It was really kind of bizarre. We were taking these flagship stores that were really snooty, and we were painting stuff all over the walls. It was very not mainstream/corporate. Somebody at the top was really diggin' it, and the guys in Portland came up with this idea of: Let's build out taco trucks, hire celebrity chefs to make the tacos and serve them. It had this weird angle to it, that if your receipt came up with whatever on [it], they gave you a free pair of jeans right then. We ended up doing one for L.A., one for San Francisco and the third one went to Chicago. The cool thing about it was they kind of just let us do our thing. One of the things that I dug my heels on in the beginning, was that I want to make sure that you can see brush strokes, and make sure that people can tell that it was hand-painted, not just some digital rap.

You can tell that your work is really intricately done. There's a lot of work and love put into it, so I can see that it's important for you to include those little details.

Thank you. You never really know if people are getting it. When I was first starting, you made the constant effort to hide the fact that you did it by hand. I've had years now, of just kind of deconstructing that, leaving imperfections intentionally sometimes. It's always going to be imperfect because it's by the human hand anyway, but sometimes I'll leave something that I wouldn't have left years ago, because I want people to engage with it, and look at it and say, “Yeah, somebody actually climbed up on a ladder and painted that.” Not slapped a sticker on in 20 minutes, and moved on down the road.

You've worked in Seattle, Los Angeles, San Francisco, and are affiliated with Portland. Those places are typically associated with design work and branding. What did you like about Denton and North Texas, compared to living in these large market areas?

Denton has this beautiful thing, it's like small-town America gone weird. It's like it went off the rails. My wife and I have referred to Denton several times, that it's like a tiny San Francisco. You get all of the broad viewpoints, all of the neat experiences, but it's on such a small scale, that you don't feel threatened like someone's going to accost you like you do in L.A., or San Francisco. I loved San Francisco, I lived there for quite a few years, but there's an edginess to a city that large. Denton, I'm almost afraid to promote it. It's like so cool right now, and so good — it's like of like I want to keep that a secret.

What are you most looking forward to as you transition back to Denton?

I had certain routines in Denton: Taking a long lunch, having a couple of beers, going to Recycled Books and picking through records and books. Then just some of the commotion of having family and friends in the area that would just pop in. Those kinds of things, you know, lifestyle things more than anything.

Do you have any plans for the space, design-wise?

There's some things that we did to the space by Mr. Frosty's that I'm going to incorporate. The space won't be open to the public. I'm not going to conceal where we are, but one of the problems that we had in Denton was week after week, we would have students from UNT in the design program that would just show up. And that's flattering, and I understand the intrigue, because they're trying to enter into a field that involves some of this stuff. But you're trying to run a business, and deal with clients and all that. You don't want to be rude, because there's genuine interest there, but at the same time, it's not practical.

What's something you'll miss the most about the Denison studio?

The quietness. There are days that I'll go without interaction with anyone. To do the glasswork, which is time-consuming, and to do the podcast, it's nice to have that quietness. But it's not nicer than having the regular, creative interaction.

What are your favorite types of paints to use?

We almost exclusively use One Shot, which has been around forever. It's been around since the '40s, it's kind of the industry standard. There's other paints that have come out that are probably better, but this is what I've always used, and I'm too lazy to switch out all of my paint.

If you had to pick one color to use for the rest of your life, what would it be?

Red. I've been over-using red for 20-something years, and I don't see that changing. You can take the most boring thing on earth, add some red and it's awesome.