Did Texas Law Enforcement Agencies Follow Proper Protocol When Issuing Their Late-Night, Statewide Blue Alert On August 16? Plenty Of Evidence Suggests No.

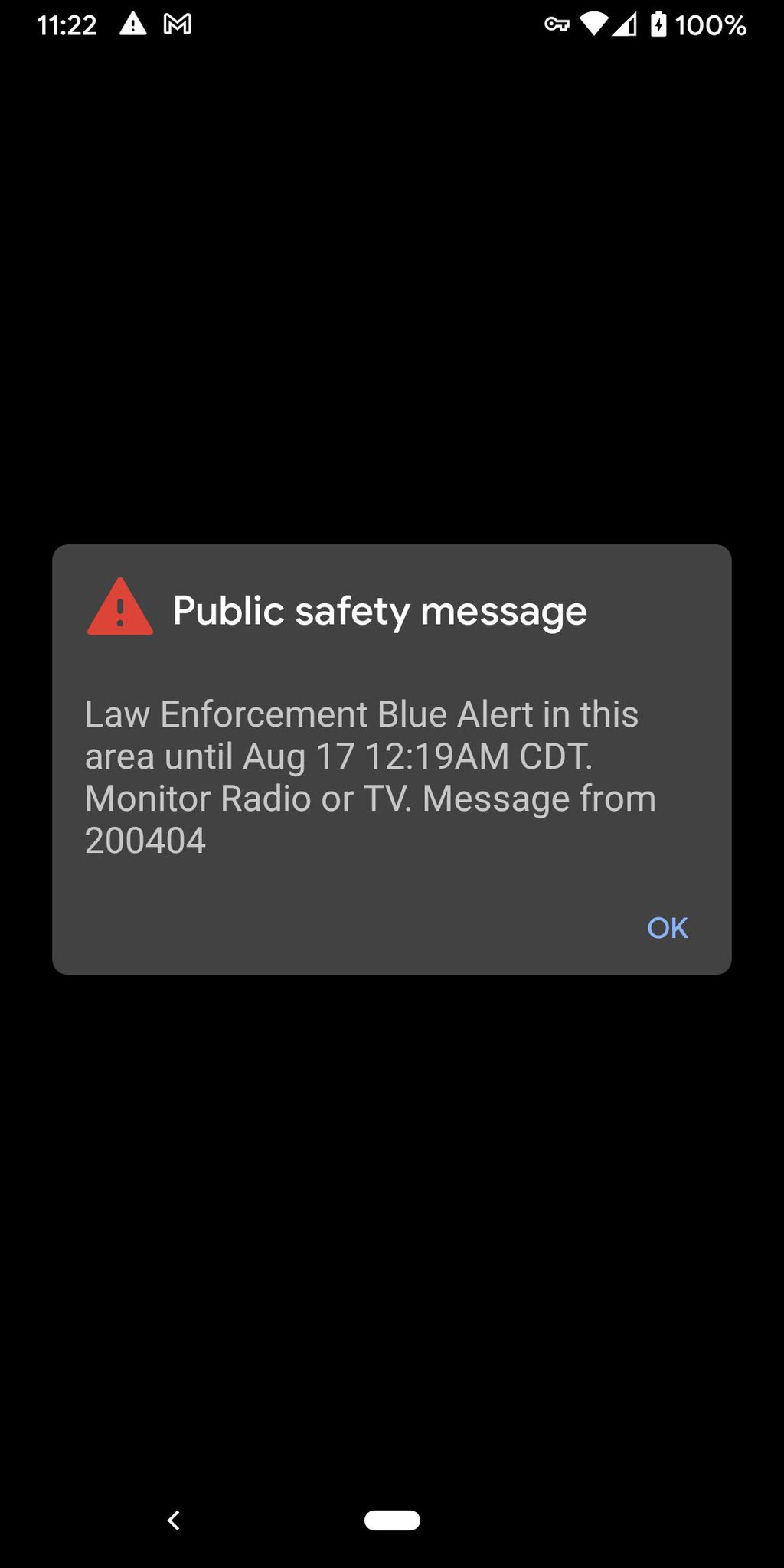

We all remember the alert that came through to our cell phones at 11:22 p.m. on Monday, August 16.

Everyone in the state — well, those who hadn’t already turned off receiving such notifications in their phone settings, anyway — received it.

And most of us were struck by the fact that the alert itself wasn’t very specific at all, which likely played in a big reason in why the term “Blue Alert” was one of the top trending topics on Twitter in the overnight hours that followed that ping to our phones.

Without much information in the message — it simply noted that a Blue Alert had been issued “in this area” and that people were to “monitor TV or radio” for more information (which wasn’t yet readily available) — it’s not at all surprising that people rushed to social media to gain some much-needed context.

But should Texans have been forced into a position where they were so actively search out that information? Probably not. Looking back on that ping now, it doesn’t seem that Monday night’s alert met the criteria in place for sending out a statewide Blue Alert in the first place. Worse, it almost certainly did not include all of the information that it was supposed to share.

A little history on Blue Alerts: When Gov. Rick Perry signed Executive Order RP-68 into law on August 18, 2008, he made Texas the second state at the time to open its citizens up for receiving these alerts. A full 13 years later, 36 states across the union now employ these Blue Alert messages as a means for alerting the public to danger and asking for their help in catching violent criminals who kill or have seriously injured local, state or federal law enforcement officers.

Monday’s alert, which came to cell phones a full four hours after a Clay County deputy was shot in the chest during a 7 p.m. traffic stop, doesn’t quite fit that billing.

A screen shot of Monday night’s Blue Alert.

Well before the alert was even sent out — and as social media users speculated about whether the alert they received was about this incident, or perhaps another one not specified by the message — Clay County officials had taken to social media to note that the officer who had been wounded in the traffic stop was doing well, and that he was expected to fully recover from the shooting.

That doesn’t line all the way up with the bar for a Blue Alert being sent out. Per the direct wording of Perry’s executive order, a Blue Alert is only cleared for transmission when “a law enforcement officer [has] been killed or seriously injured by an assailant.” Law enforcement agencies then must determine if the assailant remains a serious risk or threat to the public at large, or other law enforcement personnel, in the wake of the initial actions.

It doesn’t seem either of those were the case with the incident that spurred Monday’s late-night alert.

Furthermore, Perry’s executive order notes that Blue Alerts must contain a “detailed description of the assailants vehicle, vehicle tag, or partial tag [that] must be available to broadcast to the public.”

The Blue Alert send out on Monday night very clearly did not include that information.

In the days since the alert, the car that the Clay County deputy pulled over was found, and the shooter himself — a man identified as Joshua Lee Green of Arlington — was taken into police custody. Clay County Sheriff Jeffrey Lyde said the Arlington SWAT team found Green at an Arlington hotel around 10 a.m. on Wednesday. In the wake of his arrest, Green has been transported back to Clay County, where he now faces charges of assault on a police officer.

Reached for comment on why a Blue Alert was sent out on Monday night — and if the incident that spurred it hit all of the necessary criteria — Texas Department of Public Safety press secretary Ericka Miller defends the alert being issued across all of Texas’ 268,597 square miles.

“We would like to remind the public that Blue Alerts are urgent public safety warnings that are meant to warn people of possible danger,” she says. “They are designed to speed up the apprehension of violent criminals who kill or seriously wound law enforcement officers by generating tips and leads for the investigating agencies, and therefore giving those agencies the best opportunity to apprehend a dangerous criminal. The department initiates alerts when they are requested by an investigating agency, and [it] treats every alert activation as an urgent situation. It’s important to remember, when responding to a qualifying event, the investigating agency may not initially have sufficient identifying or descriptive information on the suspect so that can be included in the alert, and they often complete an initial investigation to determine that an alert would be useful in the case.”

Never minding that her last point somewhat contrasts with the language of Perry’s executive order, Miller further notes that there are a number of steps involved in issuing a Blue Alert — making a flyer detailing the incident, sharing that flyer to its website and social media accounts, creating TxDOT road sign messaging and, finally, sending that information to the Texas Division of Emergency Management, which is responsible for disseminating the alert itself to cell phones across the state. These things take time, she says.

By Miller’s estimation, DPS followed proper protocol on Monday night. She points to a flyer about the incident that was posted to the DPS’s alert-specific Twitter account with as much suspect and vehicle information as the department had at the time for proof. She specifically says the tweet was sent out “at the time of the alert activation.”

But while a timestamp of the screenshotted flyer shared to social media implies that the flyer itself was posted to the DPS website at 10:51 p.m., the tweet containing it was timestamped at 12:11 a.m. — almost an hour after most in the state received the alert in the first place, and long after the term “Blue Alert” had become a viral sensation thanks to curious Texans posting about the situation on Twitter.

Viewed objectively through the letter of the law, there’s reasonable doubt to be raised about whether statewide law enforcement agencies acted appropriately with the issuing of Monday’s Blue Alert.

But, then again, that’s not much of a surprise. History suggests that the rules put in place for officers, especially on social media, tend to get thrown out the window when one of their own is hurt.