The Cathedral of Hope Is More Than Just The Largest LGBTQ Church In The World.

All photos by Dylan Hollingsworth.

He says “motherfucker” and a little chorus of laughter rises over his congregation.

Elsewhere this utterance might perk some ears, widen some eyes, maybe even induce a gasp or two. And that reaction might be fair, especially when considering exactly where this utterance takes place on this Sunday morning. The sun is shining through large, stained glass windows. Pews are packed with warm bodies. And, right there in the pulpit, the portly, gray-haired interim senior pastor donning a beige robe says — yes , there’s no doubt that he said it — “motherfucker.”

It’s hardly a guttural or angry swear, but a single strand of a word hanging resolutely in a sentence within a sermon about the afterlife. And, to be fair, this isn’t some Federal Communications Commission seminar. Still, this is a church — a different kind of church, perhaps, but no matter — and hearing it in this setting remains rather bizarre.

And yet the most idiosyncratic detail about Cathedral of Hope is hardly a swear word. Peer around the church and you’ll notice same-sex couples openly holding hands — an act of affection that, presumably, would elicit either a confused or terrified response at a bevy of other churches. At a select few houses of worship such as First Baptist Dallas, it could very well cause some heads to explode.

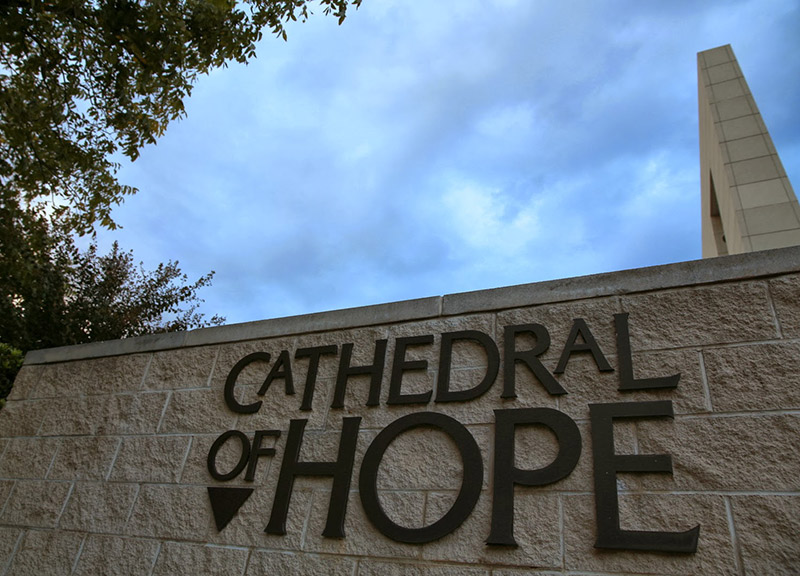

Here at this church on Cedar Springs Road, though, such acts are welcome. And they have been for some time. Cathedral of Hope was founded in 1970 when 12 people gathered in a house at 4613 Victor Street. More than 40 years later, it has grown into the world’s “largest liberal Christian church with a primary outreach to lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer/questioning people.”

Cathedral of Hope was founded in 1970 when 12 people gathered in a house at 4613 Victor Street. More than 40 years later, it has grown into the world’s “largest liberal Christian church with a primary outreach to lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer/questioning people.”

According to its own literature, the church boasts “52,000 worldwide constituents, more than 4,000 members and 1,200 weekly attendees.” It has locations in Houston and Oklahoma City, too, with the location at 5910 Cedar Springs Road in the Oak Lawn neighborhood of Dallas serving as its home base.

The Reverend Jim Mitulski, Cathedral of Hope’s interim senior pastor and the man behind that aforementioned “motherfucker” this morning, came a long way to end up here in the pulpit of this Dallas church. In many ways, it was his destiny.

As a teenager in Royal Oak, Michigan, the now-55-year-old Mitulski, like so many other teens, was inundated with curiosity and desire. That’s how he says he’d come across an issue of Playgirl in the first place. But when his father, a stoic engineer, found the magazine hidden in their family’s home, it raised some questions.

Well, OK, one question in particular.

Pejoratively and bluntly, Mikulski’s father asked if him if he was gay. Hours later, his mother, a scientist, asked the same question a little more tenderly.

Are you homosexual?

Mitulski could have lied. He knew that denying their inquisition would have meant immediate acceptance from his parents and his community.

“It was like like a little enclave of Polish culture, religion,” says of Royal Oak. “It was comfortable not to be terribly aware of what was happening anywhere else in the world.”

But Mitulski didn’t want to lie. And he had the courage not to do so. His father’s response to Mitulski affirmative answer was a vow of silence. The two didn’t speak to each other for two decades.

His father’s response to Mitulski affirmative answer was a vow of silence. The two didn’t speak to each other for two decades.

His mother responded differently.

“Don’t let anyone ever tell you that God doesn’t love you,” she said.

He was a Merrill Fellow at the Harvard Divinity School. He earned his bachelor’s degree in literature from Columbia University, and his master’s at Pacific School of Religion. He has served at churches in Los Angeles, in New York City, in Atlanta, in Berkeley and, during the AIDS epidemic of the ’90s, in San Francisco.

“It’s the thing that has marked my life,” Mitlski says of his time in San Francisco. “It was a time in history I hope never to experience again. But I’m very glad to have had the privilege of living through it.”

And not just as a bystander, either. One day in 1995, Mitulski recalls, he just got really sick — and suddenly. He was fine at noon. But, come the middle of the afternoon, he was in the intensive care unit at a local hospital. He’s remain there for several weeks, too, having slipped into a coma.

What caused the sickness, doctors told him, was an exposure to E. Coli. But that wasn’t why he so suffered on this day. That was because his immune system was weak — remarkably so.

It was then that Mitulski learned that he had AIDS. “I understand about people, that they make mistakes,” he says now. “I have made them. There’s no part of me that could ever be superior to another person’s choices or ill-thought through choices. I do think that living with AIDS is a constant reminder that there is nothing that can make you can feel morally superior to another person.

“I understand about people, that they make mistakes,” he says now. “I have made them. There’s no part of me that could ever be superior to another person’s choices or ill-thought through choices. I do think that living with AIDS is a constant reminder that there is nothing that can make you can feel morally superior to another person.

“What has sustained me was the absolute conviction that I’m not alone, even in times of stress and illness. I have been present to the life transition moments of many people when they died, and I am absolutely convinced that it’s transition from this to something else.”

Being diagnosed with AIDS did bring about a silver lining of sorts, though. It rekindled Mitulski’s relationship with his father after nearly 20 years of silence. Turns out, Mitulski then learned, his father hadn’t truly disavowed his son — not as much as he let on. Upon his father’s death four years ago, Mitulski discovered that his father had kept a file filled with various newspaper clippings featuring the numerous times that his son, the gay pastor, had been interviewed.

“Parents, y’know, they get you coming and going,” Mitulski says fighting back tears. “I’m glad that he lived long enough and I lived long enough to come to some peace about it.”

“I remember in high school, the first time reading Walt Whitman, Emily Dickinson,” MItulski says. “At that age, those are the voices that opened my world up and spoke to my spirit. The beauty of language. The capacity to describe with words — whole worlds.”

Reading books, Mitulski says, opens his mind much in the same way that the Bible does. As such, literature plays an integral role in his sermons.

“I do love the Bible and I read it all the time and it shapes a lot of my spirituality,” he says. “But I didn’t come to it until I was an adult. I was a Catholic. For better or worse, we never really read the Bible. We heard it, but we didn’t read.”

But Mitulski eventually did — and, in doing so, he switched his denomination from Catholic to Protestant, something that didn’t bode too well with his mother.

“I wish you could change,” his mother said, crying to him over the phone during his tenure in New York City in the ’80s. “I wish you could be Catholic.” “Everyone has something that upsets them,” Mitulski now says of that phone call. “Either you were a Catholic, or you were a lapsed Catholic. You would never become a Protestant. That would be just over the edge.”

“Everyone has something that upsets them,” Mitulski now says of that phone call. “Either you were a Catholic, or you were a lapsed Catholic. You would never become a Protestant. That would be just over the edge.”

But Mikulski, clearly, has different philosophies on religion than his parents did. In his eyes, religion should be used as an instrument for social change. He rejects the notion that it is a belief system aimed At preparing believers for the afterlife.

“The absolute fundamental purpose of religion,” he says, “is to transform the world in a way that reflects diversity and equality. Religion has the power to do great things, and it has the power to do terrible things. And, more often than not, when religion is used as a servant of a status quo, it doesn’t do great things. When it reinforces the individual conscience and the capacity to be non-conformist — then it does what it’s supposed to do.”

A misconception of Cathedral of Hope, Hudson says, is that it’s a “gay church,” so to speak.

“It is a Christian church with an historic ministry to and with LGBTQ people,” Hudson explains. “While the majority of attendees and members of the church are LGBTQ, there are plenty of straight friends, family and allies.” Hudson insists that Cathedral of Hope’s acceptance and “radical inclusion” is an “exceptionally strong earthly reflection of the heavenly banquet about which Jesus, the Rabbi of Nazareth, asked his followers to emulate.”

Hudson insists that Cathedral of Hope’s acceptance and “radical inclusion” is an “exceptionally strong earthly reflection of the heavenly banquet about which Jesus, the Rabbi of Nazareth, asked his followers to emulate.”

In her eyes, Christianity is simply an expression of love for all people.

“While some people want to interpret the Bible as excluding LGBTQ people, I do not hold to that interpretation of scripture,” she says. “[I] fall in line with an historic, academic and biblical heritage of interpreting scripture by taking the Bible seriously, but not literally.”

Beckett has been attending the church for about 12 years now. Allen started coming after the two became engaged to marry.

What attracts them each to the Cathedral of Hope is the fact that the church is nonjudgmental.

Allen, a black man with visible piercings, says he has felt uncomfortable in other churches in the past, sometimes fearing that his fellow congregants would throw him out because of, as he puts it, his “exterior.”  “Everything here is very friendly,” Allen says. “We’re in an open environment where there’s multiple cultures, multiple sexes, multiple orientations.”

“Everything here is very friendly,” Allen says. “We’re in an open environment where there’s multiple cultures, multiple sexes, multiple orientations.”

Beckett butts in: “I’ll put it like this: People can be who they want to be and not be judged. You walk into another church and, if you’re lesbian or gay, they look at you like, ‘Get the hell out.'”

After asking the couple a few questions, I start to seek out other congregants to speak to. Allen is adamant that, instead, he and I step outside for a private chat.

When we’re outside, he strokes a ring on his finger and begins asking questions about me. Now, it’s clear, it’s his turn to interview me.

He pulls a box of menthol cigarettes out from his pocket and lights one. He’s readying himself to ask the only question he really cared to ask.

“You don’t hate gays or anything like that?”

I get a little upset. I’m essentially being questioned about the possibility of being a homophobic reporter, one bent on writing a take-down piece about this place.

I tell him no and laugh away his concern. After our little chat — and what may have been an attempt at intimidation — I tell Lee Covington, executive assistant to Mitulski, about what just happened.

“Oh, don’t worry about that,” Covington says. “I think he’s a security guard. He gets a little protective.”