Flower Mound-Based Anime Company FUNimation Fights To Stay Relevant In a Piracy-Laden Field.

Shortly before his death, Gold Roger, the most infamous of all the world's pirates, hid his most priceless treasure. He then announced that the treasure, which has since become known as the “one piece,” was up for grabs.

Thus began the “Great Pirate Era.”

Believing that the treasure's next owner would become the king of all the pirates, Monkey D. Luffy and his Straw Hat Pirates set sail in search.

That search, which forms the basis of Japan's most successful manga series, One Piece, was originally supposed to take exactly five years. But, somewhere along the way, series creator Eiichiro Oda decided he was having too much fun. While he claims he plans on ending the series in exactly the same way he originally intended, the way he plans on getting there is in a constant state of flux — and not even Oda is sure how long it will last.

At the time of this writing, One Piece has been on the air for 14 years, boasting over 560 episodes so far.

But what is Oda's mindset? And how does one continue to stay relevant for so long when the initial product began with a seemingly finite shelf life? Tough to say. But these are also the questions that currently face FUNimation, the Flower Mound-based company that licenses One Piece in the United States.

Though companies like DiC Entertainment and Warner Bros. began outsourcing animating duties for cartoons like Inspector Gadget, Care Bears and Transformers to Asian countries in the '80s, it wasn't until the early '90s, really, that American companies like FUNimation began importing anime directly into the United States from countries like Japan. And it wasn't until a couple years later that things really took off.

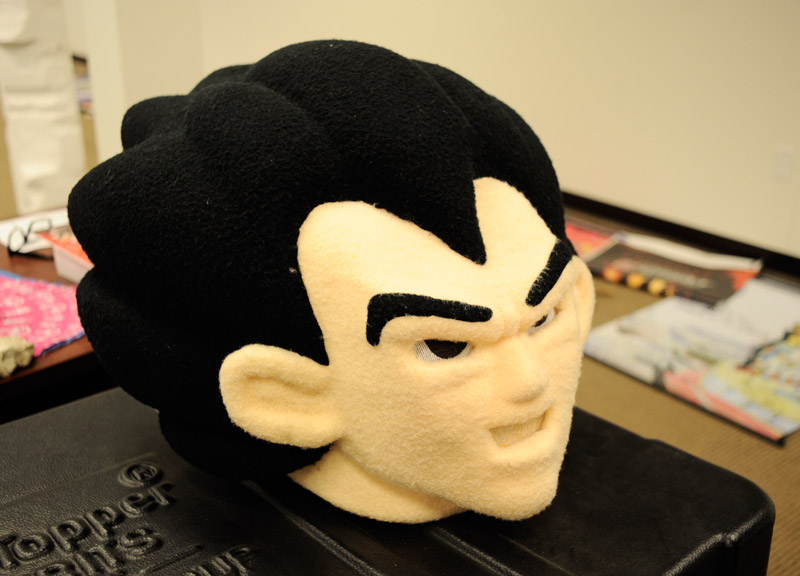

In '95 and '96, the then-Disney-owned DiC and FUNimation began licensing to the United States popular anime titles such as Sailor Moon and Dragon Ball Z, respectively. Though each of these series flopped initially, their addition to Cartoon Network's evening Toonami anime block of programming in '98 helped usher in a period now known as the United States anime boom.

And, for the past 18 years, thanks to their early success in the anime licensing game, FUNimation has maintained North Texas' status a key regional player in the anime world.

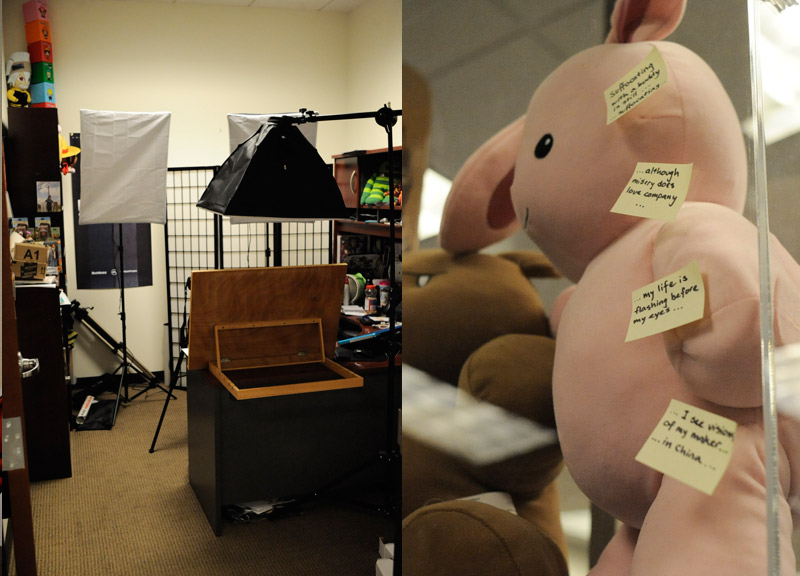

“Half of this company is from Denton,” FUNimation social media manager Justin Rojas says about the large number of University of North Texas alumni employed by the company. Much of his company's graphics department, meanwhile, is comprised of former Art Institute of Dallas students. And, overall, the company today employees over 125 North Texans as it works on over 300 active titles and hosts more than 3,000 episodes of anime on its streaming service.

But why — or, perhaps more appropriately, how — is FUNimation still a big deal? With the rise of Dotcom era coinciding so closely with that of the US anime boom, what is it that keeps companies like FUNimation in business — especially when one considers the speed of the Internet and the amount of time that exists between a show's initial release in Japan and its legally-licensed release in the States?

It's questions like these that Rojas deals with every day.

“A lot of our fans are familiar with the shows that are coming out in Japan,” Rojas says. “It's a global economy now. Back in the day, you never heard of a show until it was physically here.”

That, clearly, is not the case anymore. In the time between a title's release in Japan and the date when an officially-licensed version is finally put forth to U.S. audiences, the market becomes flooded with “fansubs.” These illegal versions have been given subtitles in several languages and are swapped via the Internet. In other words: FUNimation is selling a product that people can, for the most part, get for free. And yet the company still exists.

There, of course, is a reason. The things that Japanese audiences consider important qualities to look for in their entertainment — well thought-out and often complex story lines, for instance — don't necessarily line up with the expectations Americans have for their own flashy animations, which are normally accompanied by loud, punchy audio tracks.

Transforming the timorous-sounding Japanese audio tracks is a big key to FUNimations never ending battle against fansubs.

“Americans like to feel what they're watching,” explains audio engineer Adrian Cook as he beefs up the audio track to an upcoming episode of One Piece. While mixing and converting the “timid” Japanese audio tracks to 5.1 surround sound (a task he said takes him about eight hours per episode to complete), Cook further explains why Japan is much more of an exporter of technology than a user thereof. Tight living quarters and a close proximity of one's neighbors makes it a rare occurrence for a Japanese family to own a large television set or a surround sound system, he says. And, because they are not a wasteful culture, a high percentage of them haven't yet made the upgrade to DVD players, either.

While serving fansub sites with cease-and-desist letter is a small part of how companies like FUNimation fight against piracy, tailoring Japanese titles to better suit American tastes goes a lot farther in the end. Employees like Cook understand that a big part of their roles at FUNimation are to make their officially licensed products so much different and well-executed that they will still be purchased in large quantities by fans who've, for all intents and purposes, already seen them for free.

Other than with massive audio tracks, they accomplish this with top-notch voiceover tracks, most of which recorded in-house at their Flower Mound offices.

“It doesn't always go this fast,” says additional dialogue recording director Mike McFarland, while working on a different episode of One Piece. The actor in his sound booth, a man named Eric Johnson, who is voicing the character of Sanji, has been doing this sort of thing for years, McFarland explains.

Previously, McFarland and Johnson had provided the voices of Master Roshi and Trunks, respectively, in the American version of Dragon Ball Z. Ever since those Dragon Ball Z days, this tandem has been working with scripts that have already gone through an in-house translation team that is faced with the tasks of converting the scripts into English, finding ways to stretch out the text (it takes about three times longer to say the same phrase in Japanese as it does in English) and keeping the story line as intact as possible.

And in the rare cases when story lines don't really translate well, the shows are completely rewritten for American audiences.

“Comedy is especially hard to do because, in Japan, there's a lot of puns,” Rojas says. “Translating puns directly usually just doesn't make any sense. We have a localization team and a group of writers who do a good job at that, and they're well-versed on being able to make those modifications.”

Other times, like when there are titles that are acceptable under Japan's television guidelines but are considered inappropriate here, rewrites are also necessary. Such was the case with the show Shin Chan, which has been described as Dennis the Menace-meets-Howard Stern.

“Shin Chan in Japan is actually a kids show,” Rojas says. “[But] we're very sensitive [in America] to sexuality on TV and nudity. Some of these children's shows in Japan will have a lot more of that because they're not as sensitive to it. Like, a girl with big bouncing boobs can be OK in a children's show [over there], but here not so much. Shin Chan is very crude with a lot of potty humor and stuff. That doesn't always fly. So what we did with that one was re-version it completely to make it over the top with the crudeness and language. That's one of the very few of our releases without a Japanese track on it. It's been rewritten completely.”

In cases like these, FUNimation is essentially creating an entirely new product exclusively for American audiences. Still, even with all of these changes, McFarland and Johnson's jobs aren't necessarily easy. As Johnson voices his character, McFarland guides him through the context of the scene he's voicing, what mood his character is in and how many mouth movements his animated counterpart is making.

In recent months, their efforts have been especially important. When Cartoon Network rebooted Toonami in May of this year, three of the six titles in the block — Samurai Seven, Casshern Sins, and Full Metal Alchamist: Brotherhood — were titles licensed by FUNimation.

But, as is the case with One Piece, FUNimation also manages to fight piracy by attempting to beat the fansub users at their own game. Recently, the company has begun creating their own subtitled episodes of One Piece by streaming them on their web channel only an hour after they've originally aired in Japan.

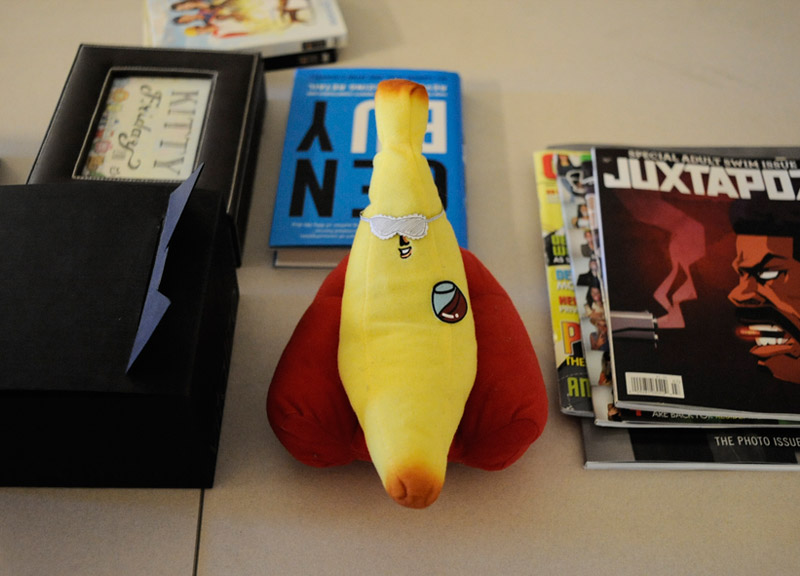

It's not all combating Internet piracy for FUNimation, though. The company is also growing their brand and expanding the popularity of anime in the U.S. in other ways. For instance? They've begun helping to produce original content. Lately, they've started working closely with the video game company Electronic Arts to create films for the popular Mass Effect and Dragon Age series. (The former, it should be noted, stars Freddie Prinze Jr. voicing the character James Vega.)

But, no matter how many ways FUNimation adapts itself with the ever changing industry, Rojas knows they will never completely eliminate the illegal trading of fansubs.

“There's always the issue with piracy,” Rojas says. “That's something that all entertainment companies have to deal with. Our fans are very technologically savvy, so we have to take that into account when releasing our content.”

Still, Rojas acknowledges, there are just some people that will never buy your product, no matter how appealing it may be. Especially when you own a treasure as valuable to pirates — real and imagined alike — as One Piece.

“People spend their money differently,” Rojas says with something of a shrug. “People who like to steal content just like to steal.”

FUNimation office photos by Jeremy Hughes.