Might Those New Shared Bike Lane Markers Downtown Be The Signs of Changes To Come in Dallas?

Dallas Torres is lucky to be alive.

Earlier this year, the Oak Cliff resident was struck by a car while riding his bicycle on the Jefferson Boulevard viaduct and suffered injuries that included a broken neck.

Sadly, accidents like Torres’ aren’t all that uncommon in Dallas. Nationally, the city is recognized as one of the worst cities for cyclists in the States.

In 2008 and once again this year, Bicycling magazine named Dallas the “Worst Cycling City in the United States,” citing the fact that, even though the city boasts a relatively small biking community, it still boasts one of the highest accident rates.

So it’s no surprise, then, that the topics of cycling and bike safety have been a growing concern for the city’s elected officials of late.

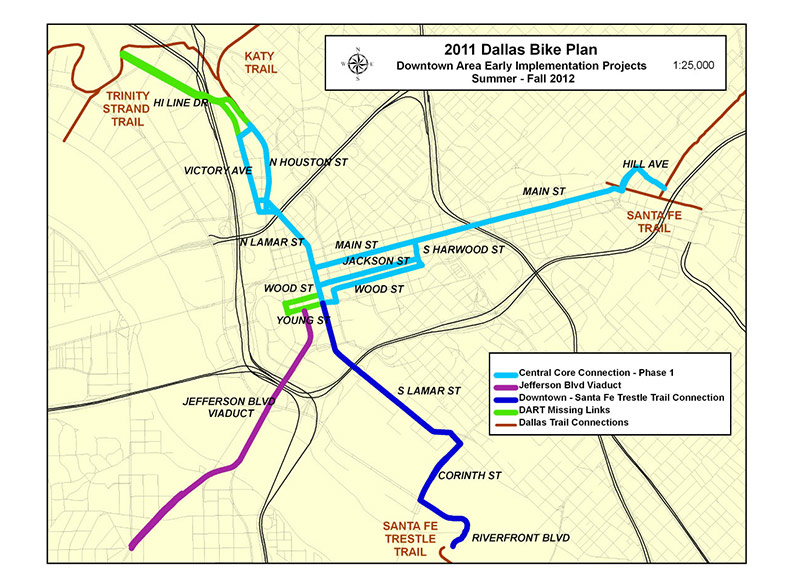

And, thanks in part to a donation of $41,000 from the non-profit Downtown Dallas Inc., the city has recently begun taking steps to implement Phase 1 of the Central Core Connector as laid out by the 2011 Dallas Bike Plan. A major feature of the plan will see the addition of bike lanes aimed at connecting the Sante Fe and Katy Trails.

You might’ve seen some of these “lanes” around town already. They’re right there, very much in the middle of Main Street in Downtown and in Deep Ellum. Only, well, they’re not so much lanes as they are painted markers that remind drivers that, hey, sometimes people bike here, too. And, according to Keith Manoy, Dallas’ assistant director of transportation planning, that’s all they’re supposed to do for now.

“Bike lanes begin to promote safety through awareness,” Manoy says. “The average motorist will take extra care when they realize a vulnerable road user may be present. Some recreational cyclists feel safer in a designated lane, too. At the very least, the cyclist knows that a shared lane provides a constant reminder that cyclists might be present. The more people riding, the faster the culture will develop.”

Called “sharrows” by members of the biking community, the addition of these shared bike lanes are meant to not only remind motorists to courteously share the road with cyclists, but to indicate where in the lane cyclists should ride, as well as to reduce the number of wrong-way bicycling incidents.

There is some debate among cyclists, though, on how much of a positive impact shared lanes will have on bike safety. While many concede that the addition of shared lanes is better than if the city was doing nothing at all, the general consensus among regular riders is that actual, dedicated bike lanes would provide a much safer solution. Dallas resident Jonathan Braddick, who has relied especially heavily on his bike for transportation ever since selling his car two years ago, argues that, while shared lanes represent a decent first step in making Dallas a more bike-friendly city, it shouldn’t be the final one.

“What you see right now are not bike lanes, but shared markers that enhance and educate the current Texas law where a bicycle already has the right to the full lane,” Braddick says. “It’s like an educational marketing campaign that puts up billboards and advertisements to showcase a product or service. It’s better than not having them. However, there are several places, especially on Houston and Lamar in Downtown where the city chose to start only with a shared marker, and not the proposed full bike lane as is recommended in the 2011 Dallas Bike Plan.”

Jim Wood, director of Planning, Transportation and Development for Downtown Dallas Inc., which helped fund the project, agrees with Braddick’s assessment.

Says Wood: “The city’s bike plan lays out a bunch of different options for shared lanes and dedicated lanes. If I were riding a bike, I think I would like a dedicated lane better, but I think shared lanes are all the city thought they could afford at the moment.”

One part of the city, however, is markedly ahead of the curve on promoting bike safety.

In August, the first buffered (read: non-shared) bike lane in the city was installed along one block of Mary Cliff Road near Oak Cliff’s Rosemont Elementary.

And, to be sure, Braddick believes habits of Oak Cliff cyclists and motorists are the catalyst that will eventually ignite change throughout the rest of Dallas.

“We’ve already seen an increase in ridership in Oak Cliff without bicycle infrastructure because of Bike Friendly Oak Cliff’s tireless work to keep it relevant by hosting so many events,” Braddick says. “People have to take it on as a part of their lifestyle, and not simply as a recreation or fitness activity. With the new bike lanes, those that would like to but don’t feel comfortable riding in a full lane without them will indeed start to make in-roads in helping increase ridership. Oak Cliff is the incubator for showing the rest of the city that riding should be a part of your daily life.”

Whether that will end up being the case remains to be seen.

For now, though, the shared lanes being painted around town do represent a minor victory for the cycling community.

It’s a victory that Manoy believes will go a long way toward promoting cycling in Dallas.

“The simple and direct answer is that bike lanes, shared or segregated, will promote cycling,” Manoy says. “In this region, cycling for sport or recreation is enjoyed by a relatively small percentage of the population. The introduction of bicycle infrastructure will hopefully help to get people onto the streets. It is important for the city to provide accommodation for alternative modes of transportation. There are health benefits to cycling and it can be a viable transportation alternative for someone whose lifestyle is conducive to shorter trips.”

Until more funds are raised by the city, the current shared lines will have to suffice.

That could change sooner than later, though, provided a $2.2 million bond package, which includes funds for further increasing bike infrastructure in Dallas, is passed on this November’s ballot.

In the meantime, at least the current lanes represent the city at least acknowledging a potential sea change.

Or as Manoy says: “Hey, it’s better than nothing.”