What Can Trinity Groves’ Present Tell Us About Dallas’ Past And Inevitable Future?

A thin layer of dust from a construction site wafts in the air for a bit before eventually settling in a thin film atop the patio furniture belonging to the nearby restaurants of Trinity Groves. The stark white rag one of the restaurants’ employees uses to clean it comes back with cocoa brown stains.

This is an everyday occurrence at this proto-neighborhood/restaurant incubator complex, which currently exists as a hive of hip restaurants smack dab in the middle of a giant construction site.

Everywhere you walk, you find mounds of dirt, orange cones, loose nails and muddy footprints. One parking lot is halfway shut down due to its current state as a lake from the previous day’s rainstorm. During the midday lunch rush, construction noises mix in with the music emanating from the restaurants.

The construction noise won’t stop anytime soon. The reach of Trinity Groves’ properties along the banks of the Trinity River is too big, the promise too real.

A few blocks over, at the corner of Singleton Avenue and Bataan Street, it’s a different story. There, you’ll find a tiny beauty salon, some small homes and Taqueria Cordova — all remnants of this area’s past. Both businesses remain operational, but currently sit on a parcel of land surrounded by properties owned by the team behind Trinity Groves. Needless to say, both will be gone sooner than later, swallowed up by the surrounding development. Already, the owner of Taqueria Cordova has hung a large white banner on the front of her building, informing the public that the property is indeed for sale. Natty Martinez, who lives in a home adjacent to Taqueria Cordova, says he heard the restaurant’s owner isn’t planning on letting her spot go for anything less than $1.7 million — a figure we haven’t been able to verify. But it’s not too surprising an amount. Looking at the place itself, that number may seem out of left field, but it’s not the physical building that is worth anything; it’s the land on which it stands.

Already, the owner of Taqueria Cordova has hung a large white banner on the front of her building, informing the public that the property is indeed for sale. Natty Martinez, who lives in a home adjacent to Taqueria Cordova, says he heard the restaurant’s owner isn’t planning on letting her spot go for anything less than $1.7 million — a figure we haven’t been able to verify. But it’s not too surprising an amount. Looking at the place itself, that number may seem out of left field, but it’s not the physical building that is worth anything; it’s the land on which it stands.

It’s the same story with Martinez’ property. He lives in a tiny one-story home butted up against another one of Trinity Groves’ properties. He laughs and talks with his friend on his front porch about the inevitability of his land being purchased by Trinity Groves’ masterminds. Around him, the powder-blue paint on the wooden siding of his house has curled and peeled from the wood. The steps to his front door bow like a warped picnic bench. A white iron fence surrounding the perimeter of his property leans over the cracked and mostly disintegrated sidewalk. Martinez knows he’ll sell sooner than later. Developers interested in buying his land have contacted him on numerous occasions. He also knows that it’s not his home they want, but the land. He says he paid $90,000 over 20 years ago for the land, and now he’s willing to let it go — for $300,000, which would be the perfect amount for him to save up and use for a possible move back to his native Mexico. Martinez laughs at the idea of asking for more than $1 million for his property like Taqueria Cordova is.

Martinez knows he’ll sell sooner than later. Developers interested in buying his land have contacted him on numerous occasions. He also knows that it’s not his home they want, but the land. He says he paid $90,000 over 20 years ago for the land, and now he’s willing to let it go — for $300,000, which would be the perfect amount for him to save up and use for a possible move back to his native Mexico. Martinez laughs at the idea of asking for more than $1 million for his property like Taqueria Cordova is.

“A million is too much,” he says. “Too much responsibility. I don’t need that.”

There’s no telling how much West Dallas Investments, the investors in charge of developing the area, is willing to put down on Martinez’ property. But history shows that they are definitely in the market for vacant land.

Come 2013, Phil Romano, Stuart Fitts and Butch McGregor of West Dallas Investments and Commerce Properties West LC broke ground on what is known today as Trinity Groves and, in a way, Trinity Groves has become the somewhere to which the once-controversial bridge now leads. Those who lamented that 1,870-foot long structure are now looking toward the area to manifest the new trends in Dallas. When city planners and developers decided to bridge the gap between Downtown Dallas and its western, nearly forgotten counterpart, this city embarked on a path that will continue to shape its future for years to come. Once the steely, the bone-white arches of the Margret Hunt Hill Bridge set foot on the sloshy banks of the Trinity River, they signaled an inevitable new era of billion-dollar investments and trendy consumerism.

When city planners and developers decided to bridge the gap between Downtown Dallas and its western, nearly forgotten counterpart, this city embarked on a path that will continue to shape its future for years to come. Once the steely, the bone-white arches of the Margret Hunt Hill Bridge set foot on the sloshy banks of the Trinity River, they signaled an inevitable new era of billion-dollar investments and trendy consumerism.

But before all of this development; before Shepard Fairey painted murals along Singleton Avenue; before the sidewalks were made immaculate; before the shiny and reflective street signs became aglow; and before foodies and young professionals parked their luxury vehicles in the Trinity Groves parking lot, the area much more closely resembled a deserted wasteland.

Dump trucks loaded with metal scraps drove in and out of dirt lots that surrounded open-air corrugated steel warehouses. Sidewalks faded in and out, but mostly out. State-Thomas district planner John Gosling told D Magazine in 2013, “It is almost like rural Mississippi. It is the last thing from urbanity.” What in the world would city developers, especially those interested in restaurants like Fuddruckers and Macaroni Grill founder Romano, want with dilapidated warehouses and overgrown patches of land? The answer is somewhat akin to playing the game of Monopoly.

What in the world would city developers, especially those interested in restaurants like Fuddruckers and Macaroni Grill founder Romano, want with dilapidated warehouses and overgrown patches of land? The answer is somewhat akin to playing the game of Monopoly.

“Common sense just said, in order to expand the city of Dallas’ tax base, you have to expand west,” West Dallas Investments’ Fitts once told D Magazine. “So we said, what the hell. We’ll just start buying land out there and we’ll hold it. It’s already at the bottom of the barrel. It had no place to go but up.”

Buying up numerous parcels of previously unwanted land became the means to make their strategy a winning one. Yet, the onus can’t solely be placed upon West Dallas Investments or even former Dallas Cowboys quarterback Roger Stabauch, who has teamed up with Trinity Groves to build apartments along Singleton Avenue.

The push southward can be credited to an initiative concocted by Mayor Mike Rawlings. In 2012, Rawlings, who at least somewhat saw the writing on the wall, and drew up a $1 billion plan to entice investors to develop in the area. One aspect of his GrowSouth project included the knocking down of 250 abandoned homes to make way for curious developers.

Similar to the Rawlings project, Trinity Groves’ investors have accrued their properties on their own and razed the land to make way for their fortunes. In fact, Rawlings and the rest of City Hall — including Stabauch’s daughter, Jennifer Stabauch Gates — devised a $3 million plan in 2015 to relocate the Argos cement plant, which will be moved out of the way of Trinity Groves’ progress and right next to the future of the children at Thomas Edison Middle School. Not much seems to stand in the way of Trinity Groves. Sure, there may be a legal snag here or there, but never anything that a call to a county judge can’t fix. That was the case when construction workers dug up a 30-square-foot family cemetery that has been dated back to 1908.

Not much seems to stand in the way of Trinity Groves. Sure, there may be a legal snag here or there, but never anything that a call to a county judge can’t fix. That was the case when construction workers dug up a 30-square-foot family cemetery that has been dated back to 1908.

Build they will at Trinity Groves, over dead bodies if that’s what it takes.

Abstract, fire-engine-red sculptures line the entranceway that leads right to him along Trinity Groves’ restaurant row. Xeriscape, fountains and immature trees surround the elongated patio. The canvas and plastic awnings of some of Dallas’ most innovative restaurants flap in the wind. The neon signs of Souk, Chino Chinatown, LUCK, Casa Rubia, Sushi Bayashi, Resto and, most notably, Kitchen LTO gleam in the background.

Without Trinity Groves’ restaurant incubation master plan, many of these lights would be dim.

Kitchen LTO, which stands out as the embodiment of the restaurant incubation concept at Trinity Grove’s current bleeding heart, has found a home here in Trinity Groves because of its willingness to give anything a try. Kitchen LTO itself functions as a sort of chef incubator. Every six months, five chefs are given the opportunity to woo the restaurant’s owners and the hungry public in order to secure their vote as becoming the next chef behind the menu.

“I was always following different trends and whatnot,” says Kitchen LTO owner Casie Caldwell. “LTO evolved out of that thinking about basically building a business model based on change, so that we keep things fresh. We keep things exciting.” The most exciting aspect about the greater Romano-helmed restaurant incubator concept is the opportunity bestowed upon these up-and-coming restaurateurs — people such as Uno Immanivong of Chino Chinatown. When Mark Brezinski, a concept consultant for Trinity Groves, approached Immanivong about opening one of the first restaurants in Trinity Groves, she was enjoying the fast success of her catering company, Foodie Couture. She was then quickly thrust onto the national stage as a contestant on ABC’s The Taste. She teamed up with the esteemed Anthony Bordain in season one, and rubbed elbows with a few stars of the Food Network like Bobby Flay and Scott Conant. And yet Immanivong was not always a restaurateur. She had spent 16 years working as a banker before she considered food as a career.

The most exciting aspect about the greater Romano-helmed restaurant incubator concept is the opportunity bestowed upon these up-and-coming restaurateurs — people such as Uno Immanivong of Chino Chinatown. When Mark Brezinski, a concept consultant for Trinity Groves, approached Immanivong about opening one of the first restaurants in Trinity Groves, she was enjoying the fast success of her catering company, Foodie Couture. She was then quickly thrust onto the national stage as a contestant on ABC’s The Taste. She teamed up with the esteemed Anthony Bordain in season one, and rubbed elbows with a few stars of the Food Network like Bobby Flay and Scott Conant. And yet Immanivong was not always a restaurateur. She had spent 16 years working as a banker before she considered food as a career.

“I left my very comfortable, secure job to do this restaurant,” says Immanivong. “It wasn’t a given [that I would open shop at Trinity Groves]. It was nerve-racking to go to some of these tastings with Phil, because I don’t know what he likes and what he doesn’t like. They were nervous about bringing someone like myself in, because I didn’t know what I didn’t know. There was so many details that I had to learn in the last two years.”

Nevertheless, she was brought on board, and she has since earned some notoriety and success during her time on Romano’s restaurant roster.

Still, it’s worth noting that she’s never really left out to the wolves, and is never completely autonomous. Like the rest of the businesses that operate in Trinity Groves, Chino Chinatown shares profits with its landlords. Each restaurant has different stipulations as to how much is split between the restaurant and its investors, but, for the most part, the profits are split 50/50.

Linda Mazzei who owns and operates Resto with her husband, chef D.J. Quintanilla, says that if Resto wanted to embark on franchising its restaurant, its contract with Trinity Groves says that overarching company has an opportunity for a partnership to help with cash flow. That is, of course, if their restaurant were to continue to garner a steady flow of success and avoid shutting down. In the past, restaurants in Trinity Groves have had to close their doors for various reasons. The very so-so (if interesting) Potato Flats, a Chipotle-style basked potato spot and one of Romano’s own concepts, closed because the concept was “best suited to a traditional pad site or other location that will allow for a quicker dining experience and/or drive-through capabilities,” a Trinity Groves spokesperson told CultureMap Dallas. The ramped-up hot dog restaurant, Hofmann Hots, lost its location once it was decided that an apartment complex would work better in its place. Most recently, Sugar Skull Café also fell victim to the conundrum of fast-casual dining in a restaurant complex that is more of a destination spot than a convenient spot to grab some grub.

In the past, restaurants in Trinity Groves have had to close their doors for various reasons. The very so-so (if interesting) Potato Flats, a Chipotle-style basked potato spot and one of Romano’s own concepts, closed because the concept was “best suited to a traditional pad site or other location that will allow for a quicker dining experience and/or drive-through capabilities,” a Trinity Groves spokesperson told CultureMap Dallas. The ramped-up hot dog restaurant, Hofmann Hots, lost its location once it was decided that an apartment complex would work better in its place. Most recently, Sugar Skull Café also fell victim to the conundrum of fast-casual dining in a restaurant complex that is more of a destination spot than a convenient spot to grab some grub.

Says Resto’s Mazzei: “When a restaurant closes, people do think ‘Oh, crap! What should we do to make ourselves better so we don’t close?”

Mazzai’s opinion is that one of the downfalls of these restaurants has been their overall ticket price. She says that short-order, fast-casual restaurants don’t last because they require five purchases to make up the amount of sales that one person garners at Resto. Basically, the rule is as follows, she says: The higher price per patron, the better chance of surviving. Take a look at the restaurants that remain in business, and you’ll see that they all avoid the fast-casual model and opt for sit-down, full-service concepts.

One soon-to-be-former Trinity Groves upstart, Four Corners Brewery, fits into neither category. They will soon be leaving their established spot on Singleton Avenue for the greener pastures of The Cedars. Mainly citing space and capacity concerns as their reasons for departing, Four Corners also says it is seeking the advantage of owning its new two-acre home in the Cedars as opposed to paying rent to Romano.

“Trinity Groves, what it was or is or will become, is, frankly, irrelevant to our business,” Four Corners managing member Greg Leftwich told The Dallas Morning News in February. “We’re a commercial manufacturing company, and they are a retail-restaurant-residential development.” As Four Corners fades out of Trinity Groves, so will many of the other businesses in the area. On the same block as the brewery, past the Fairey murals outside of Off-Site Kitchen, a convenience store is running at full swing. Dozens of men wearing dirty work clothes and smelling of a hard day’s perspiration file into the store to buy tallboy beers, cash their checks and head back home in their pickup trucks. A group of young men sit in their classic Chevrolet Impala, smoking cigars and drinking beer. A homeless man sits on the curb, asking passers-by for their spare change.

As Four Corners fades out of Trinity Groves, so will many of the other businesses in the area. On the same block as the brewery, past the Fairey murals outside of Off-Site Kitchen, a convenience store is running at full swing. Dozens of men wearing dirty work clothes and smelling of a hard day’s perspiration file into the store to buy tallboy beers, cash their checks and head back home in their pickup trucks. A group of young men sit in their classic Chevrolet Impala, smoking cigars and drinking beer. A homeless man sits on the curb, asking passers-by for their spare change.

The scene at this gas station is familiar yet oddly out of place. Someone at this gas station just bought a stick of beef jerky and a bag of chips as his dinner. Meanwhile, just 100 yards away, young business professionals pack into trendy restaurants to spend $50 a plate.

As we’ve previously reported, the La Bajada Urban Youth Farm would aim to “employ economically disadvantaged youth as paid interns, providing them an initial work experience growing healthy food and teaching them about horticulture, nutrition, cooking, and business economics.” Additionally, the food grown at the farm would be sold to Trinity Groves’ restaurants as an example of cooperation between the rooted neighborhood and the budding newcomers.

As we’ve previously reported, the La Bajada Urban Youth Farm would aim to “employ economically disadvantaged youth as paid interns, providing them an initial work experience growing healthy food and teaching them about horticulture, nutrition, cooking, and business economics.” Additionally, the food grown at the farm would be sold to Trinity Groves’ restaurants as an example of cooperation between the rooted neighborhood and the budding newcomers.

If you talk with any of the people closely involved with the Trinity Groves, they will attest to the sheer brilliance of its upcoming growth and prosperity. West Dallas Investments, right along with the rest of the developers flowing over the West Dallas levees, is prepared to take on a century-long endeavor that could be the inevitable expansion of the already mushrooming Dallas-Fort Worth area.

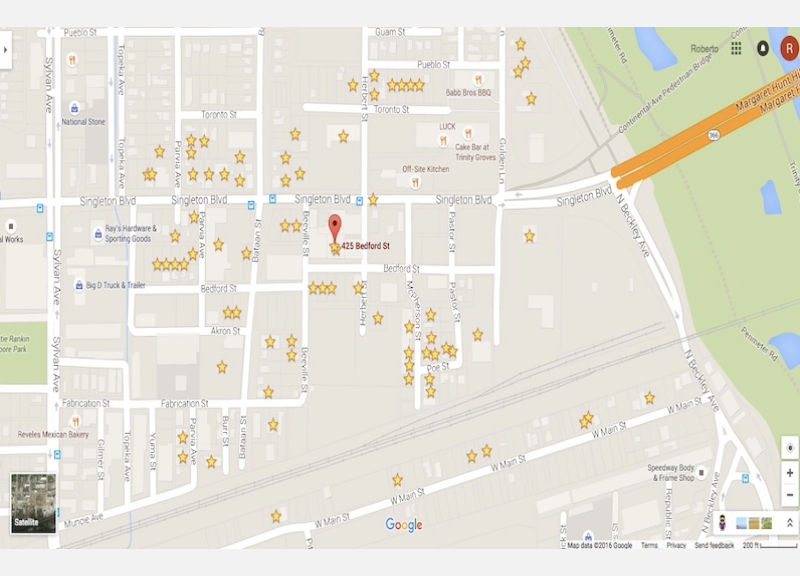

Trinity Groves isn’t alone in this task. Areas like Sylvan Thirty and the upcoming Trinity Green at Singleton and Sylvan are also pot-committed to getting the West Dallas ball rolling with amenities like restaurants and office buildings. And so the next logical step has now become housing — the next little something meant to give development here that extra push. Enter this five-story, 349-unit apartment complex, or maybe this four-story, 371-unit, Class-A multifamily project? That’s what Columbus Realty Partners and Stonelake Capital Partners have in mind, anyway. But what about prospective properties like Martinez’ home? Or Taqueria Cordova? It remains to be seen whether they will be added to Trinity Groves anytime soon — but in the meantime, West Dallas Investments and Commerce Properties West LC still have an entire other street’s worth of prospective properties waiting to be developed. Along West Main Street from North Beckley Avenue to Yuma Street, West Dallas Investments and Commerce Properties West LC, own 22 parcels of land.

But what about prospective properties like Martinez’ home? Or Taqueria Cordova? It remains to be seen whether they will be added to Trinity Groves anytime soon — but in the meantime, West Dallas Investments and Commerce Properties West LC still have an entire other street’s worth of prospective properties waiting to be developed. Along West Main Street from North Beckley Avenue to Yuma Street, West Dallas Investments and Commerce Properties West LC, own 22 parcels of land.

Usually, when you think of Main Street, you think of tall buildings or small businesses or community parks, and not this Main Street. This Main Street looks more like a deserted road out in the boonies. There are no curbs, sidewalks or even sewage drains. There are only patches of land that look like a swamp. The buildings that do exist here on West Main Street are dilapidated homes or empty warehouses. The street is mostly paved, sure, but it has deteriorated into one that would be hard sledding even for a rally car racer. On a recent afternoon — and just on cue, as if to say, “Make way for the future of West Dallas!” — a black Cadillac SUV swerves down West Main Street, avoiding potholes and kicking up a dust cloud that hangs in the air long after the vehicle is gone. Seems this road has become a shortcut for commuters trying to avoid the nearby traffic on North Beckley Avenue.

On a recent afternoon — and just on cue, as if to say, “Make way for the future of West Dallas!” — a black Cadillac SUV swerves down West Main Street, avoiding potholes and kicking up a dust cloud that hangs in the air long after the vehicle is gone. Seems this road has become a shortcut for commuters trying to avoid the nearby traffic on North Beckley Avenue.

That shortcut won’t last forever. If Trinity Groves doesn’t develop on West Main Street soon, someone else will. What they will build along this languished, historically impoverished stretch? Something, that’s for sure.

Dallas is expanding. It has to expand somewhere. And it’s already happening.

A few blocks away, the future awaits.

All photos by Roberto Aguilar.