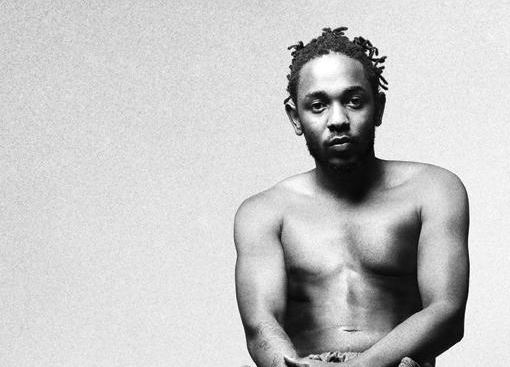

Kendrick Lamar's Sold-Out Show At South Side Ballroom Last Night Was a Religious Experience.

Have you ever had a religious experience? Felt touched by an angel, apostle or God himself? When it happens, electricity and The Spirit course through your bones. You may squeal or raise your hands to the sky or perhaps dance around uncontrollably while screaming “Yes, Lord!”

You're most likely to experience this in an actual church — probably some run down house of worship deep in the southern states, one that rattles when the choir sings. But Dallas experienced it last night at South Side Ballroom, too, at Kendrick Lamar's sold-out show that came as part of his “1st Annual Kunta's Groove Sessions.”

Immediately following Kendrick Lamar's stage exit after a roughly one-hour set that was so tight it felt like a mere 20 minutes, the crowd began chanting — not “encore,” and not “Kendrick! Kendrick! Kendrick!” Instead, the crowd began hollering “We gon' be alright!”

Earlier the night, Lamar had essentially goaded each and every one of us into this, having performed every song you'd expect already except for “Alright,” the most important one. For millennials, “Alright” has become a song emblematic of the civil rights struggle that black Americans have been facing in America for hundreds of years — basically since the “pioneers” were finally finished murdering Native Americans for their land and diverted their attention to the people who would build America from the ground up, for free. It's a nü-hymnal and spiritual that neutralizes, at least temporarily, the pain, anger and fear that black Americans feel in the face of everyday racism — micro and macro-aggressions alike — and in the preponderance of police brutality. It’s frightening to know that any day could be your last because some trigger-happy police officer was threatened by your melanin content. It's comforting to know that “Alright” understands this struggle, a ready-made replacement for “Lift Every Voice and Sing.”

And so Kendrick returned to the stage, grinning. He conducted a chorus of “We gon' be alright!” chants. He led us all through crescendos and decrescendos. It lasted for a good three to five minutes. Then, just before the anticipation reached its head, Kendrick screamed into his microphonore: “Alls my life I had to fight, nigga!”

It was the moment that undoubtedly everyone in the room was waiting to commence. And here it was, your religious experience.

The crowd moshed and smiled and sang along. Kendrick left — for real this time – to the Boris Gardiner sample that started To Pimp a Butterfly off like a starter pistol, “Every Nigger Is a Star.”

It was a wonderful ending to an incredible set from the Compton emcee. His second studio album, To Pimp a Butterfly was the subject of much critical praise this year thanks to its smorgasbord of musical notes that nod to jazz, funk, blues and hip-hop, and its lyrical content that casts Lamar as a sherpa guiding the listener through the black experience in America.

The leisurely, '70s-era stage design found Lamar and his band, the Wesley Theory, under a large pink and baby blue neon sign that read “Pimps Only.” The setup also included a white leather couch and a zebra print rug. And Lamar's performance itself was exactly the type of smorgasbord mentioned above. For Lamar's entrance, the Wesley Theory played itd own rendition of Earth, Wind & Fire's “Can't Hide Love” as the rapper sauntered onto the stage, fidgeting and cockily sizing up his opponent, the microphone. After a quick tease, he then launched into “For Free,” a cacophonous jazz number that finds Lamar arguing with a metaphor for America about how his “dick ain't free” — a crass, if effective, way to extol the virtue of how man is not for sale.

The Wesley Theory added a necessary element to Lamar's set. The band — two guitarists, a drummer, a keyboardist and a DJ — formed like Voltron to create a layer of sound unlike what found at most any other rap show. For the songs that demand live and real organic instruments — tracks such as “Complexion (A Zulu Love)” and “These Walls” — the DJ essentially just filled in the gaps to create a complete sound with backing vocals and adlibs or a little extra thump of bass. For songs that begged for a more digital and aggressive sound — efforts including “m.A.A.d. city,” “Money Trees” and “The Blacker The Berry” — the instruments just accented the backing track and only peered out from the background for choice moments, such as the guitar solo at the end of “m.A.A.d. city.”

The whole thing that was supposed to make this show special was that it had the moniker of being “intimate,” which some bullish concert promoters and fans alike took umbrage of. Those people weren't wrong; there ain't a truly intimate venue among the many housed inside the Gilley's complex. Another fact: This show would have been much better suited for the Kessler or even the Majestic. But, alas, this was still for all intents and purposes, a rap show. And intimacy is all relative. It means being close and personal. For a person of Lamar's caliber to host a show at South Side Music Hall, where the concert was originally set to take place, is intimate. Show promoter Scoremore's play to move the show into South Side Music Hall was a move made to get more of us right into the eye of up close and personal.

And it was a treat. As Lamar told us, this short tour may be the last time he ever performs To Pimp a Butterfly, which is a shame because Lamar is truly at home and masterful with this record in a live setting. But that's also what helped make this a special event and a special night.

What's intimacy if not something special?

Amen.