The Former Mayor And Prominent Ku Klux Klansman Has A Statue In Fair Park And A Highway (One That Literally Separates Black And White Dallas) Named For Him.

Black Lives Matter protests continue marching through streets nationwide.

Their calls alerting our attention to systemic racism and injustice within American society are ceaseless.

In their wake, statues of Confederate leaders, colonizers, and others figures hailing from the nation’s dark past are coming down. The same is true here in Dallas.

Dallas has seen over 60 continuous days of protests following the death of George Floyd under the knee of a Minneapolis police officer. Every night, marchers fill the streets, and their chants echo through the canyons formed by Downtown Dallas’s skyscrapers. While the protests continue to take place, the city finally rid itself of its grandest monument to the Confederacy.

Only a cement slab remains where the 60-foot Confederate War Memorial once stood in the Pioneer Park cemetery next to the Kay Bailey Hutchison Convention Center in Downtown Dallas. It took a decision from the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals in Texas to finally allow its removal, but now it’s gone.

Removing the memorial was long overdue. Its sheer size made it seem like the final boss of Dallas’ racist statuary.

Problem is, it isn’t.

A bronze statue of Robert Lee “Bob” Thornton — named after Robert E. Lee, naturally — stands to the left of the limestone steps leading up to the Hall of State at Fair Park. Immortalized here, Thornton is depicted wearing a double-breasted suit jacket and holding a Stetson in his right hand at his side, greeting visitors to the fairgrounds over which he once held sway.

Without knowing who he was, the statue appears unassuming. However, leaving it at that belies the character of the man it immortalizes. Thornton’s statue is a symbol of Dallas’ problematic and painful past.

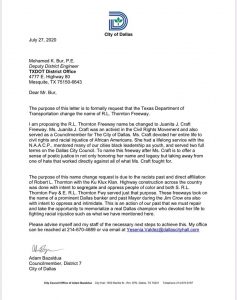

(Right-click to open Bazaldua’s letter to TxDOT in a new tab and read it at full size.)

Now, Dallas City Council member Adam Bazaldua, whose district encompasses Fair Park, wants it — and all other memorials to Thornton across the city — removed. Earlier this month, Bazaldua submitted a proposal with the City of Dallas’ Office of Arts and Culture for the Fair Park statue’s removal. On Monday, he launched a petition and submitted a letter to the Texas Department of Transportation to have the stretch of Interstate 30 currently named for Thornton to be renamed for the late South Dallas activist Juanita Craft, who openly fought against many of the racist policies Thornton helped put into place. (In 2017, a similar, but ultimately unsuccessful, effort sought to rename R.L. Thornton Freeway after President Barack Obama.)

Thornton was a prominent business and civic leader in Dallas in the first half of the 20th century. He held many roles: chairman of the Mercantile National Bank; founding member of the Dallas Citizens Council, which has its own checkered past and still holds significant sway in Dallas politics; president of the Dallas Chamber of Commerce; philanthropist; key player in landing the Texas Centennial Exhibition of 1936; board president of the State Fair of Texas; and Dallas mayor from 1953-61.

He was also a prominent and unabashed member of the Ku Klux Klan.

Thornton’s affiliation with the Klan is more than enough to justify the statue’s removal and the highway’s renaming — processes Bazaldua has now formally started. (Whether southern Dallas’ Robert L. Thornton elementary school will receive the same proposed renaming treatment remains to be seen.)

In Thornton’s day, one in three eligible Dallasites were Klan members. So, what makes him so special to be singled out? Well, for starters, he helped decimate South Dallas. By now, Central Track readers surely know all about the State Fair of Texas’ racist past and subsequent, debilitating incursions into the surrounding neighborhoods. For decades, the fair outright excluded Black citizens; eventually, leadership caved and allowed African Americans in the gates for one day — called Negro Appreciation Day, then later Negro Achievement Day. (White residents called it something else.)

Thornton didn’t see this as a problem. While serving as mayor — and president of the fair’s board — he went so far as to deny that the fair was segregated at all, when the NAACP Youth Council, led by the aforementioned Craft, began protesting it in the 1950s. Despite these furtive claims, he still maintained that concessions couldn’t serve Black people when they were allowed into the fairgrounds due to “legal commitments.”

He didn’t stop there. Before his death in 1964, Thornton helped the fair push back against integration altogether: “With Thornton’s help in the 1960s, the State Fair fought harder and longer to exclude black people, even to the point of trying to remove their homes from its borders, than any other public institution in Dallas,” wrote the venerable Dallas city columnist Jim Schutze in his 1987 book, The Accommodation.

The havoc wrought by the fair and Thornton on the surrounding communities persists today. Poverty, disinvestment and economic stagnation are the results of their efforts.

Even before the decision got hung up in the courts, the removal of the 60-foot-tall Confederate War Memorial from Pioneer Park took years to accomplish. Impeding this process was former Mayor Mike Rawlings as well as three Black members of Dallas City Council — Tennell Atkins, Dwaine Caraway, and Casey Thomas — who voted to delay its removal in 2018. (Yes, seriously.)

The future of the Thornton statue and the highway name for him don’t have to chart similar paths. And perhaps they won’t: Bazaldua says he is confident that his efforts have the support of the majority of city council, which is expected to have the final say on the matter after the Texas Department of Transportation and city’s Office of Arts and Culture kick the matter on up to their final vote as he anticipates. In the case of the statue, Bazaldua also says he already has the support of Fair Park First, the non-profit organization overseeing the management of the park, behind his effort.

But the council can’t simply decide to pluck the bronze off its plinth, swap out a couple highway signs and call it a day. Removing Thornton’s statue and highway markers are necessary, but they’re far cry from the totality of the reforms that the city must enact.

In the coming months, the council and city leadership alike have their work cut out for them. They must focus their efforts toward undoing the systemic racism, oppression and injustice that’s ingrained in so many aspects of Dallas life from housing, access to food, policing, education, jobs, transportation, infrastructure, pollution (Shingle Mountain, anyone?) and countless other issues. They’re all intertwined.

Protesters aren’t taking to the streets daily to simply mourn George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery and untold other Black lives lost in America. They’re marching because they want actual change.

A society that willingly subjects its citizens to unequal treatment due to the color of their skin isn’t a society at all.

For too many, it’s a death sentence.

Klansmen like Thornton don’t deserve to be honored. Bazaldua is right to request the removal of his statue — and right to point out, when asked, that there’s something diabolical at play in I-30, which both literally and figurative segregates much of traditional Black Dallas from its white neighborhood counterparts, is named for a man who considered himself a proud KKK affiliate.

As is the case with the argument behind the proposed renaming of a stretch of Lamar Street in Dallas for Botham Jean — another effort Bazaldua is at least partially behind — there’s real value in making sure that the people being recognized by the symbols across the city are actually worthy of the honor. There’s just no denying that.

But, at the same time, there’s far greater value in legitimately addressing the need for real equity in Dallas. Without real legislative effort there, the removal of the markers honoring Thornton — and the Confederate monuments the city has already hauled off to storage — will end up being little more than empty gestures.

Cover photo of R.L. Thornton courtesy of the Dallas History & Archives Division of the Dallas Public Library.