I Recently Attended The Texas Furry Fiesta In Dallas — One Of The Biggest Furry Conventions In The World. Here’s What I Took Away From It.

All photos by Carly May.

Historically, LGBTQ gathering spots tend to be bars or increasingly-sanitized pride events full of rainbow flags and parade floats that have come to be dominated by by corporate bank sponsors at this point.

At this point, we all know the drill.

But, right under mainstream LGBTQ culture’s nose, a new kind of queer experience has been brewing thanks to a sub-community of sorts that owes a big debt of gratitude to the internet.

I’m talking about furry conventions, which trade corporate culture for unapologetic weirdness.

For the purposes of this article, “furry” refers to a community whose members are united by their interest in anthropomorphic characters (read: animals with human traits). So much of pop-culture involves anthropomorphic characters that the audience is meant to identify with, and from Looney Tunes and Pokemon to the misanthropic mammals of Bojack Horseman, it’s no wonder plenty of people have bonded to these types of characters.

My experience in attending this year’s Texas Furry Fiesta — also commonly referred to as TFF, and hosted this year from February 27 through March 1 at the Hyatt Regency hotel in Downtown Dallas — had me wondering to myself: “Why do we not think about furry cons in the same respectful light as pride gatherings?”

This is especially of interest to me considering TFF’s considerable growth over the last decade, as it began in 2009 with a mere 542 attendees in its inaugural year and has since growing to boasting over 5,200 attendees at this year’s 2020 showing.

From Godzilla-inspired drag shows to Rocky Horror Picture Show screenings and collaborations with the wider Dallas-Fort Worth LGBTQ community at large, TFF has asserted itself as one of Dallas’ safest spaces for queer expression. And yet media coverage of the event in years past has been surface-level at best, sticking to photo slideshows without any real context that reduces the event to detached gawking — like how the Dallas Morning News once joked that the event “can be a zoo.”

It’s also rare that any mainstream coverage of furry conventions is written by a journalist who also claims the community.

I’ve been part of it for about a decade now, though, and an earlier iteration of TFF was the first furry convention I ever attended. So I figure I’m well-suited to explaining the experience for those not in the know.

A Culture Of Acceptance

When I sat down with the convention chairman, who goes by the moniker Sable Gryphon within the furry community, he spoke of the oft-understated connection between this culture and the larger LGBT community.

“This community skews heavily LGBT,” Gryphon says. “About one in three [furries] are straight, about one in three are gay and about one in three are somewhere else on the sexuality spectrum.”

According to Psychology Today research, the furry community is majority male-identified, seven times more likely to be transgender and five times more likely to identify as non-heterosexual than most fandoms.

One of several homages to the LGBT community at this year’s convention was “Kaiju Betta Werk,” a drag show inspired by this year’s theme of “Kaiju” — a sci-fi genre focused on giant monsters (think Godzilla or Pacific Rim). The first performer was dressed as Rita Repulsa — the fabulously wicked villainess in Mighty Morphin’ Power Rangers — miming along to quotes from the show before lip-syncing to “Sorry Not Sorry” by Demi Lovato.

The furry support of the LGBTQ community was perhaps most exemplified during a moment of the drag show’s intermission, when a member of the performance troupe talked about the drag company’s work with homeless youth and its campaign against conversion therapy. They told the audience “you are fucking perfect exactly as you are” — a message built at the core of the furry community’s message of self-acceptance.

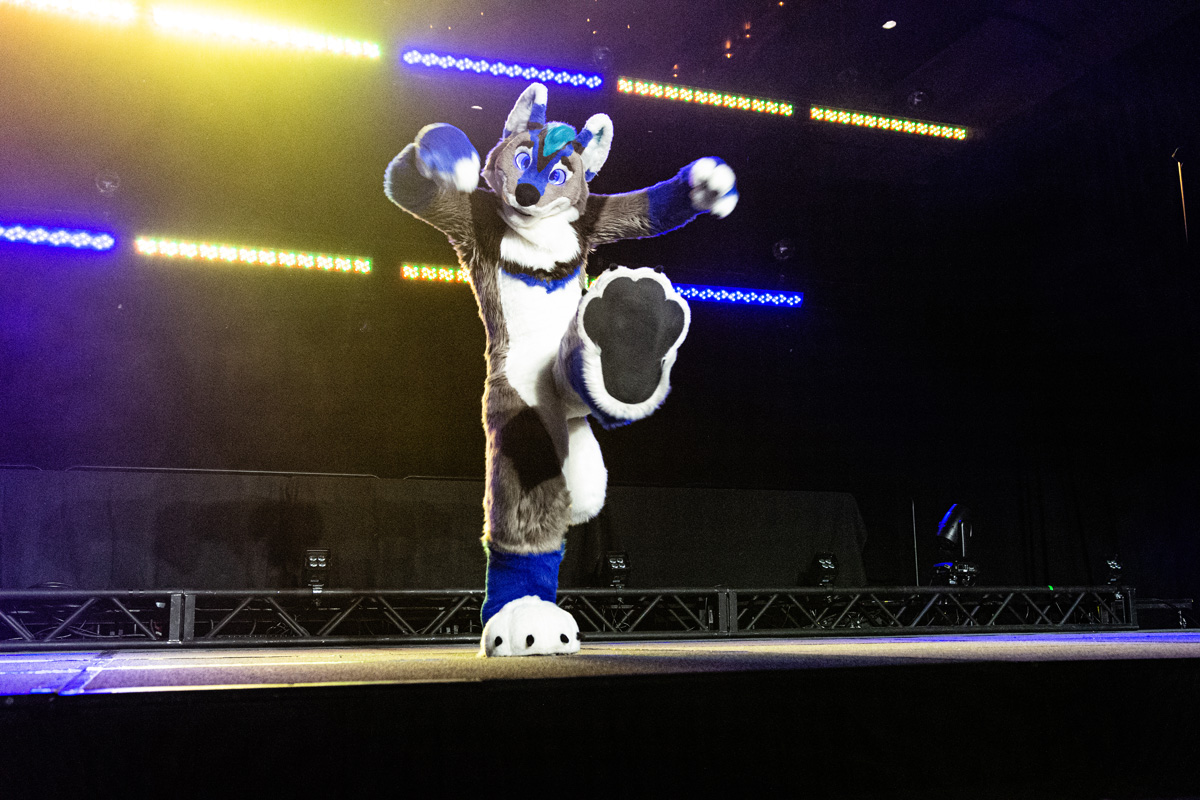

Later, the fursuit dance competition showcased novice and veteran performers alike shaking their tail feathers to a variety of songs. A recurring motif was the music from known LGBTQ ally Janet Jackson, with one suiter dancing to “I Get Lonely” and another character shimmying to “Together Again,” the latter of which was a poignant ode of Jackson’s to friends who passed away during the AIDS crisis of the 1990s. That sense of poignancy translated into the fursuiter’s performance, with their wide, fluid movements expressing resilient joy.

“This community has largely grown up around being a safe, protective space for the LGBT [community],” convention chairman Gryphon says, “all the way back to the ‘70s when we were first starting.”

The greater appeal of furry culture to LGBTQ folks can also be partially attributed to the large swath of furry content comprised of original characters, some of which are “fursonas” — versions of one’s self that represent you within the community. Furries create these characters and then often commission artists to illustrate them, as the process allows people to explore their identity in a safe, non-judgmental space. For example: Some transgender furries make characters in their preferred gender identity before later coming out as that gender themselves outside of their suits.

Personally, my identity as a gay man is inextricable from my place in furry. I met my boyfriend through this community, and he flew from his home in Indiana to attend TFF so we could be together in person for the first time since, well, the last time we were at the same convention. TFF is one of the very few places in Dallas where I genuinely feel safe holding my boyfriend’s hand, especially in light of the city’s frightening spate of hate crimes against LGBT individuals in recent years.

More established “gayborhood” venues can take some pages from TFF’s inclusivity.

Fur Mask Off

Fursuits, the costumes based on individuals’ “fursonas,” tend to get the majority of media attention at events like there, and there were indeed plenty of suiters this year. However, the vast majority of furries don’t actually own suits.

According to research taken at various conventions, only about 15 percent of furries own a fursuit. One study found that “there are many furries whose interest in furry content simply does not manifest itself as a desire to dress up in a fursuit.” Still, at this year’s event, about 1,000 celebrators lined up in full garb for the annual Fursuit Parade, in which they walk through the hotel and pose for pictures.

To write the convention off as “people dressed in wolf costumes wading through a parade” is diminishing of the community’s involvement in other convention features, though. The Dealers’ Den, a sprawling showroom where vendors in the community sell their wares, offers everything from buttons and stickers to elaborate costume heads for aspiring fursuiters.

And, although most of the art available depicted original characters, various characters from heteronormative media were given a queer re-contextualization in this setting too. Scar, the campy, limp-wristed villain from The Lion King, was depicted with a come-hither gaze on body pillows for sale in one booth.

Artists who grew up watching such stereotypical depictions of queerness refracted these images into something that better speaks to them.

Admittedly, though, the more sexually-charged pieces do raise the question that outsiders love to ask and that furries hate to answer: “So, is it a sex thing?”

Let’s Talk About Sex

For the good majority of people in the community, the furry lifestyle is not sex-driven.

If this convention was solely a fetishistic endeavor — like, say, Bondage Expo Dallas — there likely wouldn’t have been gaggles of kids walking the convention floor with their parents as there were in spades this year.

That’s not to say sex doesn’t play a tole, though. Throughout the convention, there were designated spaces for adult art, as well as adult discussions that took place at “After Dark” panels — all of which have volunteers checking attendees’ ID.

Sorry to disappoint any voyeurs, but nobody was committing Eyes Wide Shut-style hedonism in public spaces here.

As far as what may have gone down behind closed doors that weekend: Who gives a shit? As long as it’s consensual and not illegal, it’s nothing to be sensationalistic about.

In fact, I’d argue that the community’s sex-positive atmosphere goes along with de-stigmatizing conversations about sexual health in general. The Dealers’ Den, for instance, featured a booth from local HIV/AIDS non-profit, PRISM Health. There, visitors could sign up to get tested for HIV and syphilis for free.

I never could have imagined seeing such a direct connection to LGBTQ health advocacy at any of the anime conventions I misspent my youth at. My boyfriend and I even got tested at the same time.

Is This All Fur Real?

So, though I might not have an answer to my original question, I do have a crystal clear answer for a follow up: Why does a furry con matter in the bigger picture of queer community?

As event organizer Gryphon put it: “Furry is important because it allows people to explore who they are on a fundamental level. You are able to take the question ‘Who am I?’ and find the answer. We allow you to have a journey to find who you are.”

I like that answer. Because furry is not some “fandom” defined by its dogmatic devotion to somebody else’s intellectual property. It is a mode of self-expression and self-actualization — from the characters people create to the ways they celebrate those characters.

Such encouragement is why TFF continues to attract even more individuals across the sexuality and gender spectrum every year. It’s what makes the convention so special.

At TFF, attendees envision the version of themselves and their society that they’d like to see. And for three days each spring in Dallas, they get to make that vision a reality.