A Photo History of Dallas’ Gay Bars of the 1970s.

In the past few months, the United States has celebrated a few important milestones in the history of civil rights for gay Americans: the designation of the Stonewall Inn in New York City as a National Monument to Gay Rights and the first anniversary of the historic Supreme Court decision to legalize same-sex marriage in all 50 states.

But while there has been undeniable social and political progress in recent memory, there have also been stark reminders of continued hatred and intolerance against LGBTQ individuals by hateful and intolerant people — among them the recent mass shooting in Orlando and, here in Dallas, the ongoing physical attacks in and around Oak Lawn which have prompted Mark Cuban to donate one million dollars to the Dallas Police Department in order to increase patrols and to better protect the city’s LGBTQ community.

Still, as soul-crushing as news of extreme acts of violence can be, we can’t forget how much progress has been made.

Before the days of political activism, being gay was something one often kept to oneself or shared only with a close circle of friends. Arrest, loss of one’s job, and social condemnation were very real possibilities to those whose secret was discovered. Homosexuals and lesbians were often forced to keep a very low profile, if only for self-preservation.

There had, however, been gay bars in Dallas, dating back to at least the early 1950s (one of the first was Le Boeuf Sur Le Toit, later renamed Villa Fontana). Their locations were shared on a need-to-know basis, and entering these places was reminiscent of drinkers slipping into unmarked Prohibition-era speakeasies; strangers were eyed with suspicion. Establishments that catered to people who were part of what we now call the LGBTQ community were frequently raided, and the owners, employees and patrons were routinely arrested simply because they were there when the place was busted. These police raids and constant harassment continued through the latter half of the 1970s, when an organized and unified gay community became politically active and took their complaints to the courts.

Gay and lesbian bars have always held an important place in the LGBTQ community. In the early days, they were the only places where gay men and women could socialize openly with one another in a “safe” environment where they were free to be themselves.

“It’s our cultural hub. It’s our social hub. It’s home. It’s a place where you can go and quit worrying about the stereotypes and what other people are thinking of you. It’s a place you can go and just relax and be yourself.”

That was a quote from a Dallas Gay Political Caucus spokesman in a 1979 Dallas Morning News article on the emergence of Oak Lawn as the center of Dallas’ gay community. It’s hard to overstate the importance of these safe meeting places at a time when men and women were being arrested and were losing their jobs simply because they were gay.

But there is almost no mention at all of gay culture.

When a reader of my blog directed my attention to an article on Dallas’ gay club scene of the 1970s — with photographs! — I was pretty excited. The article, “Big Dallas” by Jerry Daniels, appeared in the May/June 1975 issue of Ciao!, a New York-based gay travel magazine. In addition to the photos, there was also info on at least 30 popular homosexual hang-outs from the time. (Sadly, lesbians and those of other sexual preferences are largely ignored in the article.) The piece also included several admonitions to bar-hoppers to watch their behavior around Dallas police.

It’s an eye-opening piece to say the least. Not only was it cool to see photos of buildings and neighborhoods which, for the most part, no longer exist, but it’s also fascinating to see photographic documentation of a world that was almost never photographically documented. Some might argue that bars and clubs aren’t necessarily historically important (excepting, of course, the Stonewall Inn…), but they are definitely culturally important.

The history of Dallas nightlife is littered with a staggering number of defunct bars and restaurants, most of which have been forgotten in the endless churn of time. And that’s why it’s so remarkable to see this 41-year-old snapshot of places that were vitally important in the social lives of many in the LGBTQ community of mid-1970s Dallas.

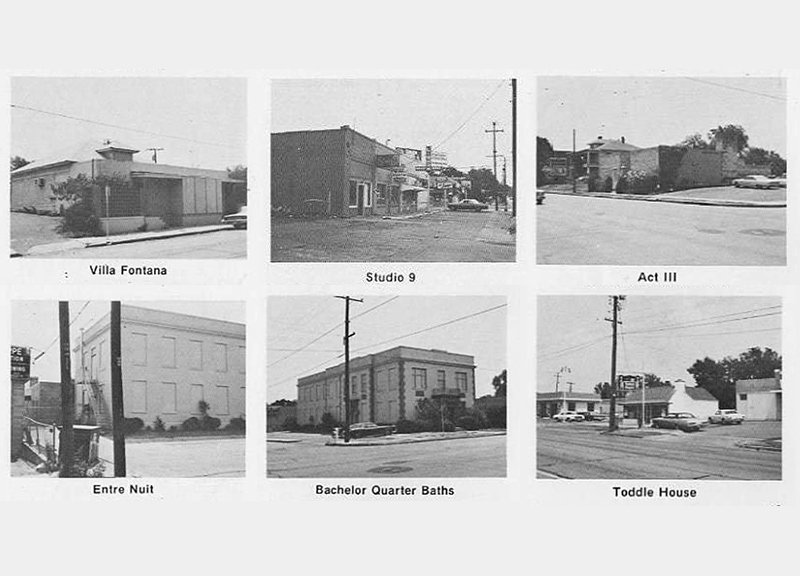

Live Oak-Area Bars

Once upon a time, the neighborhood now known as Bryan Place in East Dallas was among Dallas’ most popular entertainment options for the LGBTQ community. But it had its drawbacks, too. As Jerry Daniels, author of the Ciao! article, notes, this part of town was not one of the nicest: “On Live Oak and Skiles Streets there is a small cluster of gay establishments which are popular. I don’t like the area, though, because it’s rundown and very rough, but I haven’t heard anyone say anything bad about it, so it may be safe.”

Villa Fontana (1315 Skiles Street, across from Exall Park). Villa Fontana was the first real gay bar in Dallas. Opened in the early 1950s by Frank Perryman, it was originally called Le Boeuf Sur Le Toit (The Bull on the Roof). It was renamed Villa Fontana in 1959 and lasted at least through the ’70s. It was one of the longest continuously-operated gay bars in Dallas, and it is frequently cited by older members of the community as being one of the very few places in the ’50s and ’60s where they were able to socialize openly with other gay men and women. This cool-looking building has since been torn down. It is currently a vacant lot.

Studio 9 (4817 Bryan Street, near Fitzhugh). As described in the 1975 Ciao! article, Studio 9 was a small and “cruisy” place, and “the only moviehouse for hardcore gay ‘action’ films” in town. It looks like this building might still be standing, right across Bryan from The Dallasite.

Act III (3115 Live Oak Street, at Skiles). Act III was a popular bar that attracted a “butch crowd,” including, rumor had it, “real truckers.” It became the long-lived George Wesby’s Irish pub in 1981. It has since been torn down and is currently a vacant lot.

Entre Nuit (3116 Live Oak Street). A “friendly bar” that attracted both gay men and women, Entre Nuit hosted regular drag shows. The bar shared its large building with the Bachelor Quarters Baths.

Bachelor Quarters Baths (3116 Live Oak Street). Bachelor Quarters was a “clean, pleasantly run” bathhouse. The two-story building was built in 1928 as a medical clinic. It still stands and currently houses a CPA firm.

Toddle House (4010 Live Oak Street, near Haskell). The all-night Toddle House coffee shop was located just a few blocks from the bars and bathhouses of Live Oak and Swiss and was a popular place to grab a quick bite to eat after the bars had closed. The building has long been torn down, replaced by a parking lot which seems to belong to the Dallas Theological Seminary.

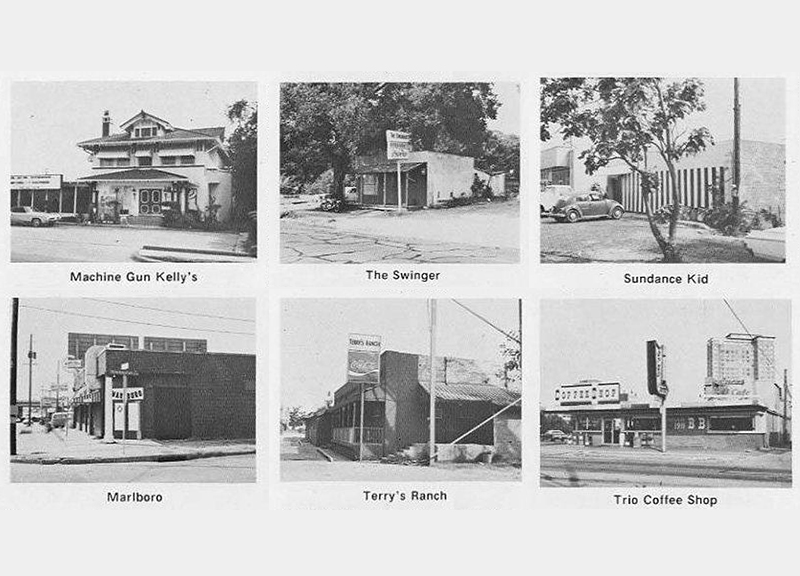

Oak Lawn-Area Bars

Even 40-some years ago, Oak Lawn was the clear hub for Dallas LGBTQ nightlife activity. In the Ciao! article, it is referred to as “Homo Heights” and is described as “comfortable,” “middle-class,” and a “very nice area.” At the time, the intersection of Oak Lawn Avenue and Hood Street was known as one of the liveliest areas in town for cruising — something that became a problem for neighborhood residents and ultimately resulted in many of the streets becoming a confusing maze of one-way thoroughfares.

Machine Gun Kelly’s/The Mark Twain (4015 Lemmon Avenue, near Throckmorton). Opened in 1974 in an impressive 60-year-old house, Machine Gun Kelly’s was a popular (but short-lived) disco-bar-restaurant that attracted “all types — straights and gays (girls too), hippies, and businessmen.” Before it became Machine Gun Kelly’s, it was another popular nightspot known as The Mark Twain, but by December of 1974 both bars were quickly-fading memories when the legendary Mother Blues moved into the old house, and there was no looking back. The house was torn down around 1983 and replaced by a strip mall.

The Swinger (4006 Maple Avenue, at Reagan). This unlikely-looking site for a gay country-western bar called The Swinger, which drew “an interesting crowd of ‘semi-butch’ cowboys,” looks like a shack out in the country. Unsurprisingly, it was a fruit and vegetable stand in the 1930s. It has long been demolished, and this stretch of Maple Avenue is now currently booming with new development.

Sundance Kid (4025 Maple Avenue, near Throckmorton). Sundance Kid was a popular “leather and western bar.” It was also home to the Wrangler Club and shared quarters with Eagle Leathers. Its building is no more; the land upon which it once stood is now part of Harlan Crow’s ever-expanding Old Parkland development.

The Marlboro (4100 Maple Avenue, at Throckmorton). Formerly a grocery store in the 1930s, The Marlboro was another Maple Avenue cowboy bar. It welcomed patrons to a free chicken dinner every Sunday. Its building has since been demolished.

Terry’s Ranch (4117 Maple Avenue, at Throckmorton). Yet another popular gay cowboy bar. Yet another building that’s long gone.

Lucas B&B Coffee Shop (3520 Oak Lawn Avenue, near Lemmon). The Ciao! layout editor appears to have mistakenly labeled its photo of Lucas B&B as McKinney Avenue’s Trio Coffee Shop. But both spots were favorite places for swinging by late at night after the bars had closed. The Lucas B&B building still stands and is now Pappadeaux Seafood Kitchen.

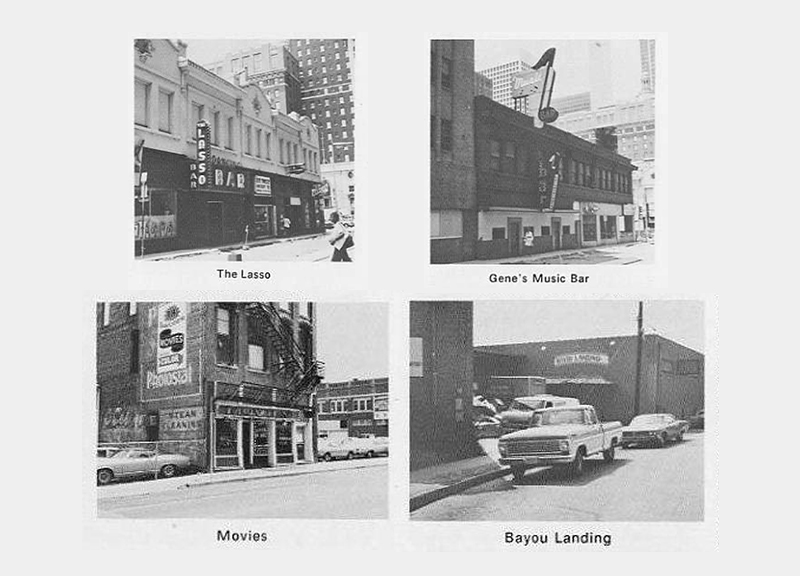

Downtown-Area Bars

The Ciao! article notes that there wasn’t too much gay activity in the Downtown area and warns that there “have been some beatings of some gays” at some of its establishments. It also notes that, with fewer spots than other neighborhoods, patrons would often “drift back and forth between the bars.”

The Lasso Bar (215 South Akard Street, at Commerce). The Lasso Bar was a rough bar with dancing, located in the shadow of the elegant Adolphus Hotel. It shared much of its clientele with Gene’s Music Bar, which was in the next block. The whole block has since been demolished and replaced by a pedestrian walkway and plaza.

Gene’s Music Bar (307-309 South Akard Street, between Jackson and Wood). Opened in 1958 as a sophisticated downtown bar that offered a state-of-the-art stereophonic sound system, Gene’s at some point transitioned into a gay bar at night while remaining a “straight” bar during the day. The Ciao! article stresses that this bar and The Lasso were both to be treated with caution as they attracted “the $5 and $10 hustlers, both black and white” who also cruised the downtown bus stations. This block has since been leveled and turned into part of the AT&T complex of buildings.

Ellwest Stereo Theater (308 South Ervay Street, between Jackson and Wood). This “popular 25-cent arcade” was an X-rated peepshow theater in a seedy part of Downtown. It boasted 18 screens of adult entertainment which played in 18 tiny rooms. As the Ciao! writer said, “It can be lots of fun if you like such places.” The police certainly liked the place: In 1978, a newspaper article reported that employees of this Ellwest Stereo Theater had been arrested at least 200 times and that vice officers came into the establishment “two or three times a day.” In the 1920s, it was the home of the Union Gospel Mission. Currently, it is a parking lot.

Bayou Landing (2609 North Pearl Street, at Cedar Springs). Housed in an old warehouse at Pearl and Cedar Springs near Downtown, Bayou Landing was one of the most popular gay clubs of the 1970s. A quick browse of the internet indicates that the fondly-remembered Landing was, for many LGBTQ youth, the first gay club they ever visited. It’s hard to imagine a warehouse in this booming part of town these days, but while the building is long gone, it is certainly not forgotten by its legion of fans.

Many thanks to JD Doyle for posting this article on his Houston LGBT History website, a site dedicated to preserving the LGBT history of Texas, with specific focus on Houston.

Paula Bosse writes about the history of Dallas on her Flashback Dallas blog. You can email her directly here.