Local Graphic Designer Ben Jenkins Is Bringing Some Swagger To Your Baseball Swing.

In his younger years, Dallas native Ben Jenkins really was an honest-to-goodness ballplayer. He played four years of Division 1 college baseball as a middle infielder at Mississippi State — and well enough to earn himself a cup of tea playing Class A ball within the Philadelphia Phillies’ minor league system.

Now, at 38 years of age, he doesn’t like to brag too much about those days.

“Guys like me are a dime a dozen,” he says with a humble shrug, recounting the number of former teammates he had who also never made it to The Show.

So, OK, as far as his baseball playing credentials go, no, maybe Jenkins’ story isn’t all that unique.

But the way his love affair with the game has played out? Well, that is a pretty novel tale.

That’s because, years after giving up on his adolescent dreams of playing professionally, Jenkins’ love for the game remained; the athletically built, scruffy looking father of three sheepishly admits that he still plays ball an average of three times a week in recreational leagues around the region. But he’s also finally found a way to make the game work out for him — if not 100 percent financially, then at least poetically.

Since Opening Day of last year, Jenkins has helmed what could arguably be seen as the hottest new commodity in the oft-dated world of the national pastime. That’s when, under the name of his Warstic Bat Co. brand, Jenkins — who, since leaving the game, had made a name for himself with his prominent, locally based brand management firm OneFastBuffalo — rolled out a product that combined of his two greatest non-family-related passions, design and the old ballgame: He started selling and promoting wooden baseball bats.

Not just any bats, either. Ones that looked every bit as good as they hit — a product that could, and indeed turned out to be, as desirable a purchase as a work of art as it is a functioning tool of the sport.

And how: His catalog features a variety of shapes and sizes, and, even more strategically, a variety of colors and color schemes. The designs are offered in seemingly every color imaginable — from purples to yellows to various shades of blue — and in schemes deemed with names such as “half-dip,” “full-dip” and the far less self-explanatory “wartip,” which finds just the top eighth of the bat dipped in a final coat of paint.

In a world so historically saturated with blacks, browns and other simplified woodstains, his designs, which recall cigarettes and World War II bomber jets more so than baseball bats, immediately stood out.

And just as immediately, they began to earn Jenkins’ modest little start-up some remarkable acclaim. In November, GQ highlighted his meticulous designs in their “Best Stuff of 2011” issue, praising their “if Pujols met Warhol” aesthetic. Next month, the bats will be featured in an ESPN The Magazine piece on the growth of superior graphic design ideals sneaking their way into the world of sports gear.

“It’s been a great year,” Jenkins admits with a smile.

Indeed it has. Warstic’s success, although still somewhat small in the bat world, has allowed Jenkins’ OneFastBuffalo design brand, which has done work for everyone from American Airlines’ in-flight magazine American Way to Dallas’ West Village shopping center to mainstay regional Tex-Mex restaurant El Fenix, to take on fewer clients and streamline their efforts. It’s also allowed for Jenkins to launch another boutique sporting goods brand, Treadsmith Board Co., which focuses on bare-bones snowboards made without what Jenkins views as tacky, over-the-top artwork.

With both Treadsmith and Warstic alike, Jenkins downplays the notion that there’s any genius to his work. He says it all boils down to simple branding, something that he thinks other companies have let slide in these markets.

“Doing the bats, I was just really trying to come up with a product that I could enjoy, that I could do, where I knew that branding was going to make the difference,” he says. “I mean, wood bats? Wood bats are wood bats. You can make a bad one. But it’s not that hard to make a good one.”

Beyond that, Warstic’s secret all lies in the bats’ post-carving design — a touch that the workers in these factories he used to build the bats initially balked at.

“The first time I ever told them to stain half the bat and then let it dry, and then paint it again, they were like, ‘Huh?'” Jenkins says with a laugh. “It just takes a little pushing and then they’ll do it. But, really, the look of the bat has nothing to do with its success, except for how it affects the brain.”

In many ways, Jenkins admits, Warstic’s business model is just confidence scheme. Hitting a baseball, he says, is all about believing that you can. Every ounce of your self needs to trust that you can indeed wield your round bat into making solid contact with a speeding round ball. Standing in the batter’s box, Jenkins continues, is not unlike entering a battlefield. If you’re not mentally prepared for a war, you’re going to lose.

That’s where the brand name comes from, of course, but there’s more to it than that, Jenkins says. There are countless factors that can contribute either positively or negatively to an at-bat experience, not the least of which is the look and feel of the weapon resting in a batter’s hands — the two things Jenkins’ enterprising brand emphasize the most.

“Hitting is not even 50 percent mental,” he says. “It’s 85 percent mental. It’s like golf or tennis. You can be gifted or whatever, but if you don’t have it up here in your head, you suck. So I’m trying to design into these bats a good, tough mental attitude, just by the looks. Hopefully that transfers.”

So far, it seems to be doing just that. No Major League ballplayers use Warstic bats at the moment, but, more than anything else, that’s the result of various color regulations put on those players’ equipment and an annual $10 million insurance policy needed before a any big leaguer can use his bats in a game.

But big league players aren’t in the market Jenkins sees for his boutique brand anyway.

“Most bat companies will just kiss pro players’ asses,” he says. “But it’s not like that’s where bat companies are making money, selling to pros. It’s amateurs — like good college players, good high school players. I don’t care if it’s a good 14-year-old or whatever. They’re the ones whose asses I’m kissing.”

The respect seems to be mutual.

“Sometimes, a 12-year-old kid might email me, and say, ‘Hey, man, I really love your bats,'” Jenkins says, for once allowing a little pride to show through. “If I get the sense that he’s a really good kid — a good, honest kid that just really loves baseball — I might send him a bat just because I like him. And then maybe his teammates will see it and buy some, too.

“That’s all I’m trying to do. I don’t have some huge marketing fund. A big bat company can just flood the market with a bunch of free bats and I just can’t do that. But I think it’s OK. I’ve never spent a single dollar on advertising and I’ve got all this really solid PR. And I know that people, when they get the bats, they’re happy. I don’t have to worry about that. I know I’m making good, quality bats. Plus, I’m not of the belief that everything good has to be big. I”m just trying to support me, my wife and my three kids. This bat company doesn’t need to support tons of people.”

It would appear that Warstic is already supporting Jenkins and his family just fine at this point. The Lake Highlands home that he also offices in could itself be featured in a GQ spread, with its carefully placed furniture, its worn wooden floors and its quirky, mid-20th century adornments — not the least of which includes the ’67 Plymouth Barracuda parked in his garage, and the shimmering Airstream trailer that doubles as his second office and is parked out back, right next to his kids’ swing set.

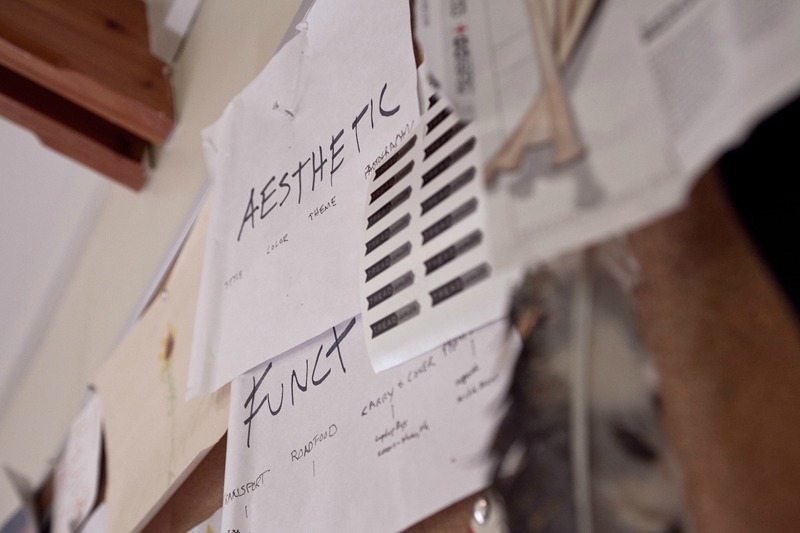

“I just figured I needed products to sell where branding made the difference,” Jenkins says. “So you think about bats and the only thing that’s different about bats is the name of the company and the aesthetics of it. And I figured I could make something people might want, so it was just applying what I did in branding to baseball bats, finding a way to get them made, figuring out logistically how that works and then putting them online just to see what happens. A bat is just a piece of wood. Every baseball bat starts with the same palette. So what can you do, when people see your bats from 30 or 40 yards away, to make them recognize them as yours? This. And it looks so weird on a baseball field these days, you have no idea. It’s just not normal.”

And yet on the other hand, Jenkins argues that it’s perfectly normal.

“To me, it’s in human nature to decorate shit,” he says. “Bats were bats and then someone painted one and there you go.”

As a graphic designer, doing that much to his love for baseball just felt natural to him. Now he’s considering expanding his Warstic brand to include designs for more baseball gear, including equipment bags and, just maybe, gloves. He just can’t help himself from toying with these ideas, he says. It’s the old ballplayer in him, the side of himself that he never quite could suppress.

“Baseball’s like a bad girlfriend,” Jenkins says with a laugh. “You know she’s bad for you and that you should stop, and that she’s giving you all sorts of mental anguish, and yet you keep going back. But when I started this company, it definitely made it fun again. I had quit playing for two months before I launched the company. This was after I’d told my wife I’d quit when I was 30.”

Standing before a row of bats carefully mounted on a wall in his office — a sanctuary littered with a number of his past branding successes but now most prominently covered with his Warstic designs — he grabs the first bat he made under the Warstic brand, a weathered, red, half-dipped Model 19 ash beaut.

He handles it gracefully, lifts it upright and squeezes its handle. For a moment, he looks very much like an active ballplayer.

After staring down at his grip for a moment and perhaps contemplating a swing, he looks back up from his creation and lets the bat fall down to his shoulder.

He may not be the ballplayer he once dreamed of becoming, but the game clearly still resonates with Jenkins. And now he’s finally resonating back with it.

“Now,” he says with a laugh and a devilish look in his eye, “I tell my wife I’ll quit when I’m 40.”

God help her if she believes him.

All photos by Hance Taplin.