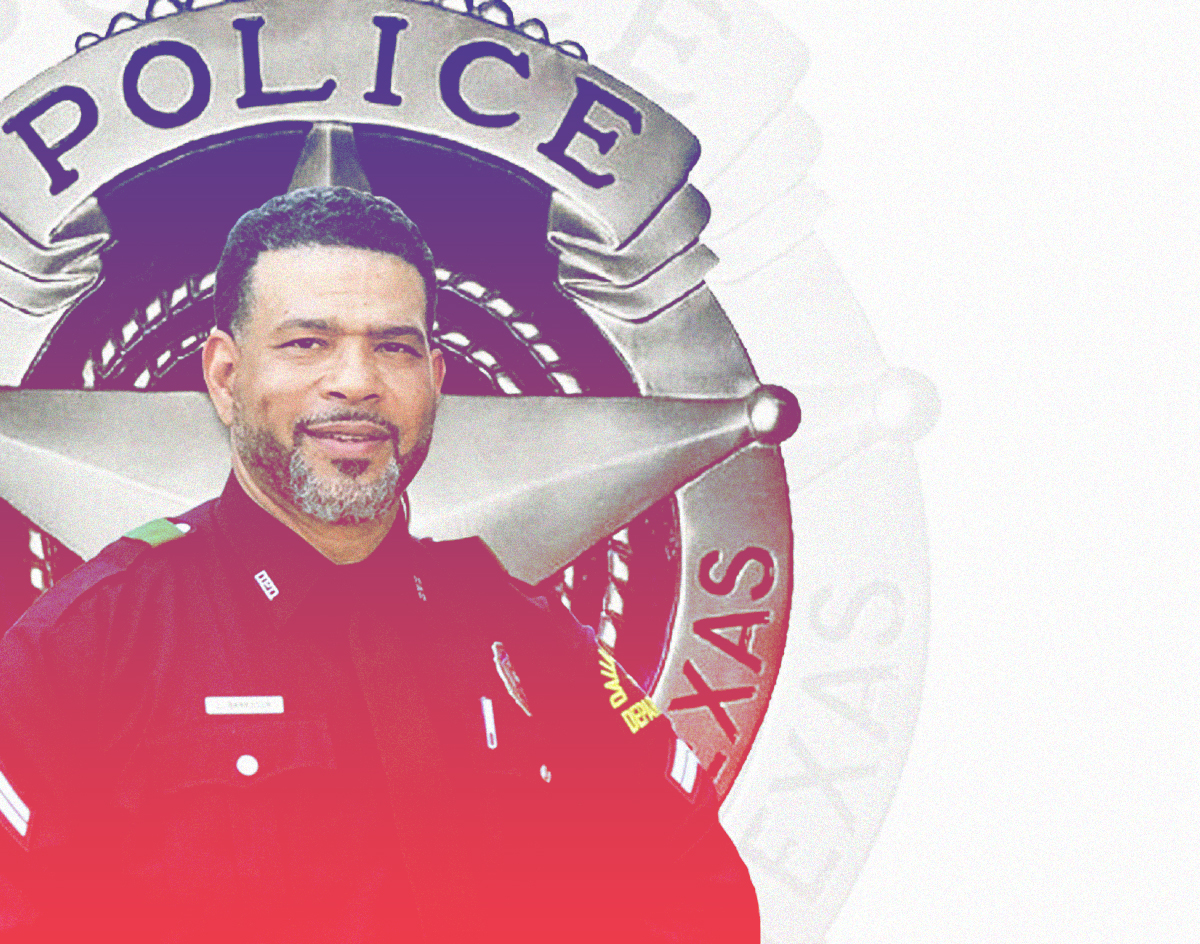

In His Own Words, Sr. Cpl. Larry Bankston Candidly Shares His Thoughts On Where The Dallas Police Department Needs To Improve.

I first met Larry Bankston, a senior corporal in the Dallas Police Department, outside of DPD HQ on Friday, June 5, as part of the department’s “Blue for Black Lives Matter” rally and march.

One thing I learned pretty quickly about the Kansas City-raised cop is that he, along with a handful of his colleagues, is not afraid to share his ideas.

“It’s not just the police department that we feel like we’re being mistreated by,” the 17-year veteran of the force told me, speaking not as an officer but as a Black man. “It’s the overall system. Say, for instance, [the way] someone of color is sentenced versus someone of European descent who is sentenced. There’s a lot that has gone on in the Black community that was never addressed — and it was caused by this country.”

Bankston wants to be clear: He loves his country. He’s passionate about policing, too — especially about reforming it. Above all, he believes, officers and civilians need to learn and institutionalize new ways of interacting with the community, most of all with regards to patrolling, mental health and the war on drugs.

Since our first meeting, Bankston has served as a source for Central Track articles about the first four days of protests in Dallas this summer and about police unions. He’s shared his opinions on “less-lethal” weapons, DPD’s overall response to the George Floyd protests and his private observations surrounding contemporary policing.

Last month, prior to Chief Renee Hall announcing her intentions to step down from her position atop the department, I spoke with Bankston by phone for an hour and a half about how DPD can reshape itself for the better.

In his own words, here’s what he has to say — and completely in his own words.

Situation Report

“For the Black community, the trust for law enforcement is legitimately low. And I would be lying to myself to say that I didn’t understand why; I get it, 100 percent, why it’s low. I mean, that system of law enforcement has been used to oppress that group of Americans for centuries now. It is changing. But you can’t expect for something like that, that’s been so devastating to a group of people, to just change overnight.

Change is gonna have to start with leadership. The leadership of these municipalities are gonna have to understand that they’re gonna have to encourage their officers to create relationships with the communities that they patrol. And they’re gonna have to start psychologically incentivizing officers to create those great relationships with the communities that they’re serving with their patrol. It can’t be chiefs coming out every blue moon, having coffee with citizens of a certain area, just to say, ‘Oh, I came out.’ That’s like politicians coming out kissing babies. It’s all smoke and mirrors. It’s bullshit.

If you live in an affluent community, the likelihood of you encountering patrol officers on a regular basis is very low. You might see them at the gas station. You might see them at your local restaurant, or something like that. And you guys speak. That’s about the extent of it. You can afford to live in a community that can pay for the security that these poor communities can’t. That means that officers and citizens in poorer communities are going to engage with one another a lot more than officers in communities that are affluent. So, with that being said, those are the two groups that need to be sitting down, having this conversation that you and I are having. It needs to be the patrolmen and the citizens, saying, ‘OK, what works for you? What doesn’t work for you? And why? What has worked in the past?’ If we are documenting history for lessons, let’s do that.

You have to realize, you’re two humans dealing with one another. I could be going through a divorce as an officer and having a rough go at it. I’m talking about things that I’ve experienced. I recently had to put my oldest son out, because he just — I don’t know what his deal is, I think he’s afraid to go out into the world and just do his own thing. But it was stressful. I had to say, like, ‘No, man, you gotta go.’ When I say, ‘I had to put him out,’ it’s like, I gave him a deadline. I don’t know if he had made arrangements to move into a place or anything, but I gave him a year and a half. And I had to say to myself, as a parent — not as a policeman, as a parent — I had to say, ‘The best thing for me to do is just kick him out of the nest.’ And he’s just gonna have to figure it out. I can’t even worry about where he’s going. So I just had to do that yesterday. Yesterday was his deadline. You see where I’m going with that?”

Dehumanization

“We have to create an environment where the boots on the ground — the officers and the citizens that are interacting with one another — feel comfortable with coming up with laws and policies that fit that dynamic, versus allowing the people that are politicians and wealthy to determine how we interact with one another. Because somewhere along the line, we take out the human aspect from both parties. And when both parties interact with one another, they try to enforce certain laws and policies — and it often turns bad.

You might have something simple: An officer might have a situation where he pulls a guy over, or a female over, and you realize that it’s really nothing, but that person is agitated. Like the Sandra Bland situation. The state trooper could have just cut her ticket and let her go. He let his emotions get the better of him.

Another example: There were some panels where they had police officers and different people from different backgrounds. The one that I’m speaking of right now was at T.D. Jakes’ The Potter’s House. You had a panel of officers and politicians, and they were talking about the civil unrest. And Bishop Jakes played the video of the situation in Buffalo, New York, where the officers push down the older white gentlemen. And he asked them, What do you think of this?

One of our guys — I don’t care for his politics; I really don’t know him that much as a person, but I know how he was an officer, and it really bothers me that he’s basically drank the Kool-Aid to the point where it’s almost embarrassing — but anyway, the officer’s answer was, ‘Well, you see how the young officer bent down to help the the gentlemen up? He’s taught to care for the citizens and take care of them. Look, that was his instinct to reach down and help the guy up!’ That was his answer about that video. And I was like, ‘Wow, that’s such bullshit.’

Then the Black Police Association, the guy over it, he kind of skated around the question as well. He said, ‘Well, those guys are not really trained to stop and render aid when they’re on that line, dealing with a protest or riots or a situation like this. They’re really not taught to stop and render aid.’ And I said, ‘Once again, that’s the problem.’ It’s bullshit. They’re not giving the answer, to me, that needs to be given.

This is my opinion. To me, the answer was, ‘Why did you put your hands on that older man at all? He wasn’t being threatening. He wasn’t doing anything that warranted you pushing him to the ground like that. You could have simply assisted him to the sidewalk out of the way of the officers and then got back on the line.’ It wasn’t any kind of threat. It wasn’t a threat at all. There was no need to push the man down.”

Working with Community

“There’s a time and a place for running and gunning. I was on a task force back in 2007 or 2008, and for a while there — like, two years — me and my partner, we led the city of Dallas in felony arrests. I don’t know if we lead drug arrests, because of the narcotics division, but we were definitely, definitely competing with them. Not purposely, but it was just happening like that. We were getting a lot of guns off the street, a lot of wanted people for serious crimes, like murder.

It wasn’t happening because we were doing some sort of spectacular investigative skills, police work or anything like that. It was happening because we created such good relationships with the communities that we were going into, that the staples of those communities, they would come to us and say, ‘Hey, that’s a crack house over there. It’s causing a lot of problems. We don’t want it here.’

I remember even the New Black Panther Party saying, ‘Hey, we’re not about hate or anything like that. We’re all about protecting our community. So there was a lady that killed a guy. I know you guys are looking for her. This is where she is. And we’re gonna help you get her.’ And the guy actually played a roll — he was like an actor — to get into the room for us to get her. And we got her.

The point I’m trying to make is, you’re just as effective when you work with the community and are creating good relationships with them to get the big fish that you really want.

It doesn’t matter if I’m a police officer or not. You take the time out to see when someone’s in crisis, and I think that from both sides of the coin. Like I was telling you, I just had to put my son out. I was a little bit in crisis yesterday, and even into today, having to put him out, because I don’t know his mindset. I’ve been through a divorce while I’ve been on the department. And I had a rough go at it during that time. But you’re talking about someone that is very conscious of the community.

Think about someone that’s not as conscious of the community, that’s going through crisis and he’s a police officer. And then you get these two dynamics coming together. You got citizens in crisis and you got a police officer in crisis. The two meet on the street, sometimes, and that is explosive.”

Approaches and Appearances

“It’s all psychological. That is where the focus needs to be — on the psychological aspects of policing, and how the officers and the citizens can be ambassadors of each other.

Take drugs. It’s still psychological. Why are you making this decision? Why are you using the drugs? You’re using the drugs to self-medicate. What are you self-medicating from? It’s what is the root of your problem.

There are terms that are used that I hate. When you try to go into the community and you want to have these discussions, you’ll hear certain officers say, ‘Y’know, I’m not down with hug-a-thug.’ And I’m like, ‘I’m not down with that damn slogan; don’t say that shit around me again.’

I literally just had this whole situation happen where there’s a guy over in the West End Transfer Center that two other officers don’t like. For two years now, these two officers keep messing with this guy. They think that he’s selling dope or some shit out of this little buggy. He’s selling oils and soaps and toothpaste and t-shirts, and he gets Nikes from over in China that are, like, the older models; he’ll buy those to sell on the street.

I’m like, ‘He has a vendor’s license. He’s doing what we want young people to do. He’s being an entrepreneur; he’s making legit money. Why do you guys keep messing with him?’ And it got to a point where we ended up in the lieutenant’s office because, I don’t know, it was like they were trying to say — I don’t know if they were trying to say that I was helping him sell dope or something. I’m like, ‘Well, if you haven’t caught him selling dope in two years, then either he’s a genius or you’s a sorry-ass officer. Because it’s been two years and you ain’t caught him with shit. But I do know that you’re harassing him. You’re harassing him in my area. And I don’t like it. I don’t care if it’s when I’m not at work. He’s coming to me with this complaint, and it’s not right.’

How are we supposed to take care of our citizens if we’re allowing this to happen? Now here’s the kicker: He’s a young Black guy. The two officers that are harassing him are Black. And when I brought it up to the lieutenant — the lieutenant is white — I said, ‘Hey, with the climate of our country, would this still be happening if that was two white officers doing that to him?’

What Are You Gonna Do About It?

“There’s a few steps that we believe that would help in changing the dynamic, and it needs to be something that’s going to be consistent and sustainable. I call them business districts. I don’t see it happening anywhere. But, to me, we need to press local and federal governments to give poor communities the ability to open business districts, or build business districts, within their communities — kind of like the Bishop Arts District or Deep Ellum. Those same districts should be in South Dallas or Oak Cliff. And I know Oak Cliff is Bishop Arts, but I’m saying in the poorer communities. Where you allow Miss Williams to open up a soul food restaurant, Mr. Green to open up a gaming cafe. All this stuff is in one area. Because, if you allow that, then you can work with your local law enforcement to say, ‘OK, we’ve created these business districts to help everybody — not just in this community, but the whole city of Dallas. Because now we’re creating economic growth.’

Once you create economic growth, we need to start creating an environment where those people can buy — versus renting — the houses in that community. That will get them to invest in the community, versus renting. When you invest in somethingm you take care of it better. That’s why I say it’s all psychological. When you own something, you’re gonna have concerns about, like, ‘OK, how can we build this without the drug addicts stealing the supplies and the equipment to build it?’

That’s another problem we need to address. We need to address the mental illness and the drug addiction. That goes back to putting pressure on the federal government. We need to do something about mental illness; there needs to be facilities created where they can go and get real help — not where we put them in Parkland and they rotate out within 24 to 72 hours. Or jail. That doesn’t work.

My thought on that is: There’s a lot of land out in the county. If you put all the social services, clinics, and everything that they need out on that land, but also you create agriculture — you put farms out there, kind of like Bonton, you put animals, you put stuff where they can actually learn something — you not only keep them busy but they actually generate money. It could be internships for potential nurses, teachers, police officers because they would need security out there.

We have things that we believe can be solutions. But we just need for people to hear us. We need a voice now.

How to institutionalize my work? That goes back to funding. The funding is part of my proposal. If officers don’t have any sustained complaints in a certain area, they should get a quarterly bonus for not having any sustained complaints. Now, if they have a sustained complaint, it should take away from the whole pot. Not just you — it takes away from the entire pot. Because that way you hold the whole group accountable. I think that would be good. Because then other officers will come to that officer that’s constantly screwing up and say, ‘Hey, man, you’re messing up my family’s goals by doing dumb shit. Cut it out or take your ass somewhere else or quit.’ I think that would happen.

At the same time, I feel like the community needs the same incentives. Like, if a family makes $50,000 or less, if that family and those communities are making the honor roll, and they’re doing community service and they’re doing all these great things to better themselves and their community, we need to give them an incentive as well — a bonus every quarter. And then at the end of the year, it needs to be an annual event. This is my dream, where the community gets to pick out who they deem Officer of the Year. And you have maybe Amazon or Netflix, all these big companies, get involved and they give that officer a huge prize. And then officers get to pick out Citizen of the Year, and the same thing. They give that citizen a huge prize, and it’s made national. We have social media and stuff; it doesn’t have to be on the TV, it can be on social media. Like, ‘This officer won Officer of the Year and here’s why.’ And ‘These citizens won Citizens of the Year — voted by the officers — and this is why. And then this is what they won.’ This is the incentive. Like, for example, they’re going to Africa.

The reason why I say that — travel — is because Black communities were terrorized into staying in one area by white Americans for years. And that’s what we’re dealing with today. The echoes of that terrorism is causing the negativity going on in those communities. Now, it’s up to the Black community to recognize what happened to them. But it would be admirable for America to say, ‘Yeah, we did that. We did that, and this is how we’re gonna redeem ourselves from it. We’re going to help them change the dynamic of these babies that are being raised.’ And then it’ll eventually get to a point where that stigma is gone. But, right now, there’s nothing in the history that’s ever been done to change that psychological dynamic that happened in that community. If anything, it’s been enhanced by smoke and mirrors. Like, ticketing poor people constantly to show that you’re doing police work. That’s oppressive because they can’t afford to pay those tickets. They turn into warrants, they go to jail, they lose their jobs. They’re oppressed even further.

Going Forward

“The last thing you want to do is defund the police. If anything, you want to put more funding in the police, but do it in a way where it’s regulated, and it’s done properly, where it creates sustainable, consistent change that is positive for the communities and the police versus negative.

You hear people say, ‘Well, demilitarize the police and this and that.’ And I’m like, ‘Aargh, you don’t want to do that.’ First off, we’re not as militarized as you think. The actual gangsters on the street have better weapons than we do; they definitely have better ammunition. We don’t come to work to get hurt. That’s one of the things that I hear people say: ‘Why do so many people show up to this call?’ Because we’re at work. And if it takes 10 officers on one person to make sure no one gets hurt, that’s what it should be. Now, if it’s 10 officers and everybody starts shooting at one person? Yeah, that’s crazy — unless that person is shooting at police or something like that.

It seems like officers that don’t want to have these discussions that you and I are having. They know what can happen, but they’re not looking at the totality of the circumstances. They’re only looking at it from one side — both parties — and that’s what we need to stop. The public needs to see, ‘OK, wait a minute. These officers know what they’re doing. There’s a reason why so many showed up to a call. There’s a reason why they brought this armored vehicle over here. There’s a reason why they snatched that door off that house really fast and went in fast because they’re not trying to get killed. They’re trying to go home.’ There’s a way you have to do things that are safe.

Like I was saying earlier, some officers escalate things that shouldn’t be escalated. And that needs to be addressed — but it’s not. Across the nation, so far, they’re not encouraging officers to do what reform-minded officers are doing. We’re doing this because we just have the heart to do it. We’re not doing it because they’re saying, ‘You guys are gonna be Officers of the Year.’ We’re not even on their radar for that type of thing. And this is not me wanting that award. I just want to be a pioneer for that change.

We want our police departments to take pride in their communities — and the communities to take pride in their officers the way people take pride in their favorite NFL team.

So that you’re rooting for each other just like that.”

The interview has been edited for length and clarity.