Looking Back Upon, and Almost Remembering, 50 Years at Adair’s Saloon.

In a place like Deep Ellum, where venues feel compelled to throw a party to celebrate the fourth anniversary of their reopening, transience hangs around like a regular. Little, it seems, ever really lasts.

Spots as beloved as the Green Room close and then open again, with little more than a shrug. It’s just the way things are here. Places have their run, and then it’s over and somebody takes over the space, changes the name — or basically just co-opts it — and that’s pretty much it.

It’s inevitable. It’s the natural cycle of things in Deep Ellum.

Well, everywhere except for Adair’s.

S.L. and Ann Adair’s saloon first opened sometime in 1963 — the exact date is something of a mystery, like a lot of things about Adair’s in its original location on Cedar Springs near Oak Lawn. The general consensus is that the bar opened in either February or November of ’63, according to current owner Joel Morales. Any paperwork that once existed and could verify an exact opening date has long since gotten lost in a City Hall filing cabinet. Interestingly, the date most often guessed in connection with a November opening for Adair’s is the 21st — the same day President Kennedy arrived in Dallas for his fateful trip.

Back then, Adair’s was recognizable, but decidedly spartan.

“This is what the original Adair’s had,” Morales says. “It had a jukebox, draft beer and then you could get a hamburger and chips. That was what they did.”

In 1983, though, the bar pulled up stakes and moved into its current Commerce Street location near Good-Latimer Expressway, bringing its no-frills vibe, bar top and graffiti-covered wood paneling to the far west end of Deep Ellum. The move, precipitated by the sale of the bar from S.L. to his son R.L. and his daughter-in-law Lois in either 1980 or 1981– again, no one is really sure– was the birth of contemporary Adair’s.

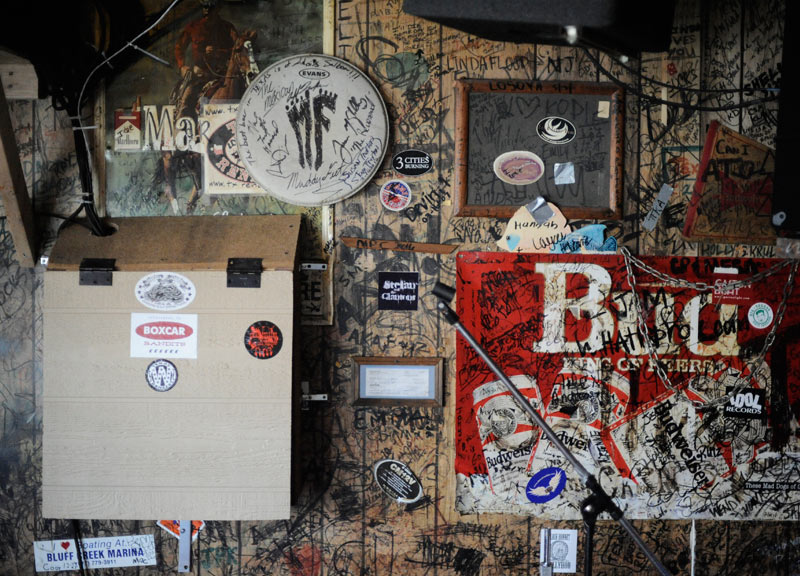

For the bar’s first decade in Deep Ellum, its evolution was mostly incremental. Soon after the move, the bar received permission from the TABC to sell liquor for the first time and added fries to complement its by-then famous burgers. The jukebox was still the only music in the joint until 1992, when a small stage was added to the back of the bar.

But, before long, that stage and its eventual successor at the front of the bar would turn Adair’s as one of the most important small venues in the Texas country scene.

That intimacy, ensured by the small size of both the stage and the bar itself and abetted by the bar’s knowledgeable crowd, make it a valuable proving ground.

“You have to be a little fearless to play at Adair’s because the genre of music is so defined that you pretty much either just sink or swim,” Carmichael says. “[The crowds] know what they like and they know what they don’t, and so if you roll in there as a country band playing in a country venue [and you aren’t good], you pretty much figure that out pretty fast.”

Like its crowds, the bar itself doesn’t coddle bands.

“Adair’s is bright — that’s the other thing. It’s really weird when you’re playing Adair’s, because, y’know, the lights don’t get turned down, the TVs don’t get turned off, nothing changes,” Carmichael says. “You just start playing music, that’s it. You have to earn the attention of the crowd and there’ve been times, depending on the crowd, that we did not.”

When a band does earn that attention, it is rewarded — not only with the adoration of a tough crowd, but with opportunity for consistent bookings, like the vaunted Monday night residency currently held by Cody Foote’s Sugarfoote & Co. Before Foote, the Monday night residency was held by the King Bucks, and before that it was maintained by local alt-country heroes Eleven Hundred Springs, who recorded maybe their best-known work, 2010’s Live at Adair’s, right on the bar’s stage.

“I mean [Eleven Hundred Springs’ history on Mondays], that’s something that we were talking about when we were contacted and started talking about the residency,” Carmichael says. “We were like, ‘Oh man, this is the Monday night residency.'”

The King Bucks took the residency, playing three hours every Monday night for almost 18 months. There, the band worked their way through its second studio album, Bar-B-Que Drugs, and found an audience.

“We built a really large fanbase off [the residency], and that’s pretty cool,” Carmichael says. “We had some crazy, crazy times on those nights — but good times.”

Even now, as the band has moved on from its residency, it takes the lessons it learned at Adair’s on its travels.

“Even when we play at Granada, we try to play as close together as possible,” Carmichael says, explaining the band’s constant efforts in trying to recreate the camaraderie that Adair’s tiny stage mandates.

“Cross Canadian Ragweed, Jason Boland, Randy Rogers, Stoney Larue and Reckless Kelly,” remembers Morales, ticking the names off. “All those guys have passed through here at some point in time, you know. It’s just kind of a stepping stone place. Everybody that’s come through [the Texas country scene] in the last 20 years has played here in some way shape or form.

The bands — like the King Bucks, who played the bar’s first of many 50th anniversary shows taking place all year long — keep coming back, too, often long after their stature outstrips Adair’s diminutive confines, speaks volumes.

One of Morales’s best memories — using the term “memory” loosely — at the bar is a show Cross Canadian Ragweed played well after becoming something of a big name.

“The last time they played in here, it was on a Monday and there might have been a hundred people,” Morales says. “And, man, it was a blast. They got liquored up, we got liquored up and they were just playing whatever they wanted to play.”

When pressed for more details, though, Morales reveals another common refrain from the history of Adair’s: He doesn’t remember much.

“When you get a group like the King Bucks, the crowd and vibe is much rowdier, the drinks flow more and the night kind of ends in a brown out,” recalls Adair’s regular Paul Merrill, who’s haunted the bar since moving to Dallas in 2009.

Carmichael agrees: “I’ve seen a lot of shows there, and some of them, honestly, I don’t remember. I would almost be willing to say I probably don’t remember the best ones, honestly.”

Still, Adair’s — as an idea, as a concept — sticks in the memory of those involved even if the details behind the genesis of that idea often do not.

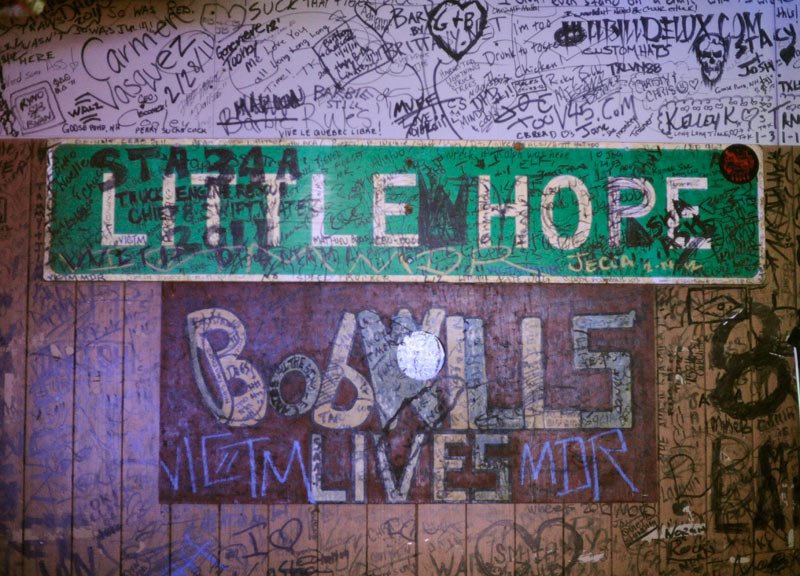

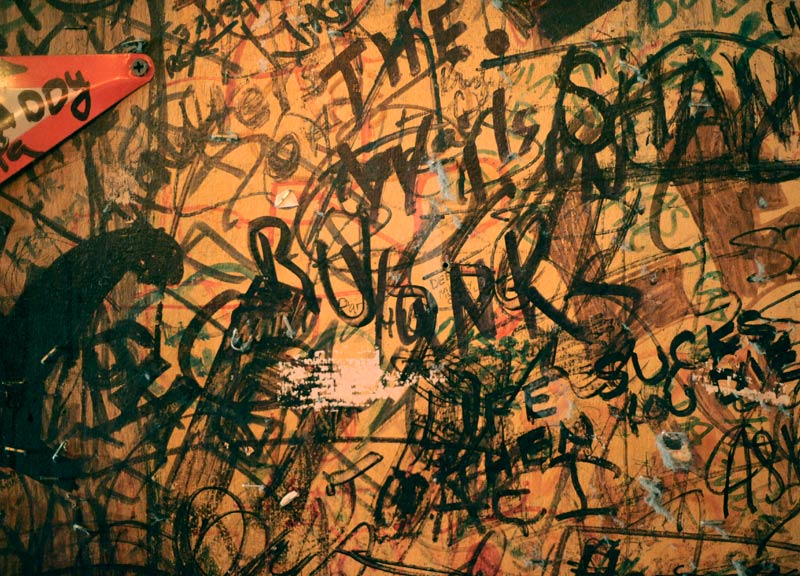

The graffiti, which took over the wood paneling at the original location, now covers not only the walls but everything else in the bar, save the TVs and the shuffleboard table. For the uninitiated, it’s a jarring visual. The names, exploits and hometowns — along with the remnants of soon-to-be-forgotten Saturday nights — of seemingly everyone who’s ever patronized the bar are there, writ large, to be seen by all who come after, or at least until they fade away and make room for the next generation.

“The writing is literally on the wall,” Morales says, glancing around his bar. “Fifty years of it.”

People want to see the history and make themselves a part of it with the Sharpies provided at the bar, says Barry Annino, president of the Deep Ellum Foundation, which offices two storefronts down from Adair’s.

“Every time someone comes to visit, I take them to Adair’s so they can write their name on the wall,” he says. “The most unique thing about Adair’s is its consistency. It never changes. There’s hamburgers, there’s music and you know what the drinks will cost. Even during the downtimes, [Adair’s] has had uptimes — because people will head down there no matter what.”

Morales and his business partner, Marty Monroe, have taken pains to keep that vibe alive since they bought the bar in 2006 from Lois Adair, who had been the sole proprietor of the bar since the death of her husband in 1987.

“Whenever we took over in ’06, it was pretty much the bottom of the barrel at that point in time,” Morales says. “Then, six or eight months after that is when they rezoned everything down here to clean up the area — clean up the landscape so to speak and everybody had to get an S.U.P. And it kinda started the rejuvenation and the rebirth of Deep Ellum.”

Morales and Monroe were longtime regulars at Adair’s before becoming owners and were hand-selected to carry on Adair’s simple legacy. And that’s what they’ve done, nothing more — well, beyond expanding the jukebox a bit beyond classic and Texas country (and, let’s be real, when adding Led Zeppelin and the Rolling Stones is considered a “departure,” you’re not really going out on too much of a limb) — and nothing less.

“That’s one of the things about this place,” Morales says. “There’s not a lot of other places that have [this]. I don’t know if it makes it more difficult or what the word is — but, when we took over, we had 43 years of expectations.”

Much of those expectations from the bar’s come-as-you-are ethos, which, despite the hole-in-the-wall grit, is omnipresent in the establishment.

“We’ve got a front door and a back door, and it doesn’t matter where you come from — race, color, creed, how much money you make, what your last name is,” Morales proudly boasts. “Everybody checks their baggage at the door and when they walk in. Everybody’s on an even playing field.”

For instance? You really shouldn’t come in the front while a band’s playing, he says, unless you want to get stared down by the whole place.

“I remember being nervous the first time I went to Adair’s,” Merrill says. “But pretty soon I found myself getting into the music, despite never really hearing Texas country before. Between the music and the cheap beer, I knew I was in a special bar.”

And he just kept coming back — especially to see bands like Carmichael’s King Bucks and fellow Adair’s mainstays Grant Jones & The Pistol Grip Lassos, while drinking seemingly countless pitchers of Lone Star and Shiner. If you ask him what stands out most about the time he’s spent at the bar, though, and he’ll tell you that what fights through his sudsy haze isn’t a show at all, but the time he took his father-in-law to Adair’s to split a pitcher.

“I was sitting there with Bill, my father-in-law, and in walks a dominatrix leading a guy in gimp get-up around the bar with a dog collar and chain,” he says. “They walk in the front door, past the band, with everyone staring at them and ordered a shot at the bar. Down the hatch it went, and they walked back out the front door. The episode couldn’t have taken more than four minutes. It was wild. Everyone in the bar had a ‘What the fuck?’ look on their face.”

That’s no small feat in this bar, considering that when Morales recounts things like people riding motorcycles and horses in through back door and out the front door, he barely even bats an eye.

“Just as soon as I say I think I’ve seen everything here,” the owner says, “something comes along and just completely blows my mind and it’s like ‘Well, no, I’ve never seen that. Alright, good deal!'”

Ask anyone about Adair’s and the second thing they mention is the burgers. The first thing might be different — the bands, the cheap pitchers, the graffiti. But, after that, after they get past their personal thing, they’ll get to the burgers, because the delectable half-pounders are one of the most universally lauded menu items in a city full great restaurants. Morales thinks keeping it simple, as it does with most things at the bar, is behind much of the praise.

“You take a bare-bones hamburger and cheeseburger that has mustard or mayo, lettuce, tomato, pickles and onions, the bare necessities on it, and put it up against mine and I’ll take mine,” he says. “For real. I mean, it’ll compete with anybody’s, when you get to the basics.”

Yes, it’s in the basics where Adair’s truly shines. For 50 years now, from start to finish, Adair’s has provided as complete of a basic dive bar experience as one can find in Dallas.

“They’ve been around, what, 50 years?” asks Annino. “I say, ‘Here’s to the next 50.”

All photos by Jeremy Hughes.