Two Years Removed From Micah Johnson’s Attack On Cops Following A Peaceful Downtown Dallas Protest, It’s Time To Address The System That Spurred His Rage.

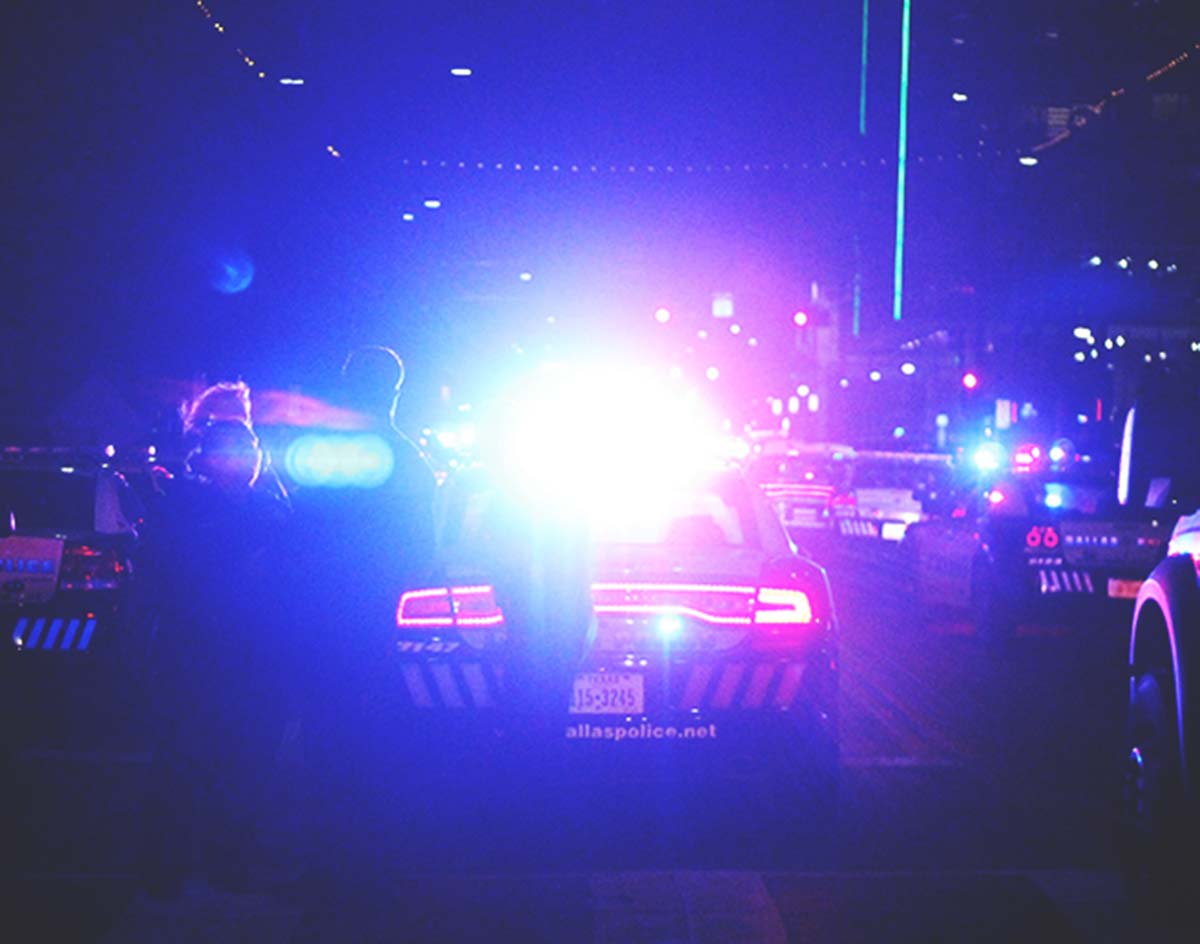

Our city nears an uneasy anniversary: Two years ago this week, Micah Johnson murdered five DPD and DART officers right in the heart of Downtown Dallas.

On the evening of July 7, 2016, Dallasites rallied to voice their outrage over a spate of African American men killed by police officers. Two days before that march, Baton Rouge police murdered Alton Sterling. Just the night prior to the protest, Philando Castile was shot and killed by an officer in suburban St. Paul, Minnesota.

Despite temperatures in the upper 90s, many Dallasites — some armed — gathered on that sultry night in opposition to such violence. DPD and DART officer were naturally on hand, keeping watch. Then, as the event wound to its close, the peal of rifle fire pierced the air and the peaceful protest turned to panic and chaos. On the block around El Centro College, five officers laid slain. In a nearby parking structure the perpetrator, Micah Johnson, was cornered. After an hours-long standoff, DPD detonated a robotic bomb killing the gunman.

In the aftermath of such violence, people looked for a motive. Racial resentment seemed the obvious answer, as Johnson targeted white officers and much of the resulting coverage emphasized his penchant for radical black politics. In the ensuing months, a flurry of lawsuits — some filed by relatives of the officers killed — targeted Black Lives Matter, DeRay McKesson and Louis Farrahkan (among others) for inciting violence against police officers.

The aftermath also saw observers — Dallasites, mainly — trying to make sense of this episode by comparing it to the city’s most (in)famous episode of violence: the assassination of JFK in November 1963. The parallels are tempting. El Centro is mere blocks from the Texas School Book Depository where Lee Harvey Oswald (supposedly) fatally shot the President of the United States. Both shooters — like so many perpetrators of public violence — were disaffected young men with lackluster military records who put their training to use in carrying out their murders. But these comparisons are circumstance; they do little to make sense of the violence. Perhaps the thing that really brings these two shootings into conversation is that they both happened in a city that was and is deeply divided.

It’s a fool’s errand to try and talk about Big D as being just one place; Uptown and Fair Park might as well be different planets. Segregation, in every sense, has long been just a fact of life for Dallasites. Of course, it’s one that the more affluent prefer not to think about. By design and by circumstance, Dallas has ossified into two distinct places: One, roughly north of Interstate 30, is rich, connected, comfortable with the status quo and mostly white; the other, found roughly south of I-30, is poor, disconnected, restive under a regime that’s slow to change and mostly black and brown.

Though their actions were 50 years removed from one another, Micah Johnson and Lee Harvey Oswald both represented have-nots in a Dallas completely dominated by its haves. And, angry at a city and nation that left them by the wayside, they each turned to violence.

After Kennedy was shot, Dallas wanted to understand itself — a murdered president will make folks rethink some things. This job first fell to a novelist and Neiman Marcus executive, Warren Leslie. In his attempt to explain what kind of city Dallas really was, he focused on violence and right-wing politics. As he revealed, 1900s Dallas politics was dominated by a group of business leaders — the Dallas Citizens Council — whose wealth made it easy for them to pull the strings of a city council elected at-large. Their opposition to progressive politics surprised few and, as the mob that met Texas’s favorite son — LBJ — in 1960 would show, right-wing opposition was popular with the people, too. Oswald — a Marxist himself — did not find a happy home in Dallas.

But Leslie’s biggest observation when trying to understand Dallas was division. He saw not one Dallas, but multiple “cities in the middle of nowhere.” Mainly, he found divisions in the north and the south. In the south were Oak Cliff and the slums of West and South Dallas; in the north were the luxury apartments of Turtle Creek, Downtown and “fashionable” North Dallas. Through an unequal distribution of wealth and resources, he found that the north dominated the south, and that those living south of 30 lost touch with the mainstream, lost out on the wealth pouring in the city and were eventually left behind. The Dallas of 1963 was an alienating place for the have-nots.

But the Dallas of 2016 and on through to now isn’t all that different. The north has prospered and the south has languished. Dallas remains one of the most segregated cities in the nation as a result of decades of racist housing policies, and a citizenry largely unwilling to enact change.

The numbers are truly appalling. One fifth of all Dallasites, and almost one third of children in the city, live in poverty. These numbers are among the highest in the nation. Of those children mired in poverty, 90 percent live in only 50 percent of the homes in the city. But poverty, while affecting large numbers of citizens, is concentrated in Dallas, mostly in areas isolated from opportunity. It is a problem confined to the south, and yet it is one that holds the entire city back, even as much of the north lives in extreme affluence.

The Dallas that witnessed the violent spectacle of a president murdered did a poor job of dealing with the fallout. Dallasites north and south experienced disbelief, followed by shame and anger at being labeled the City of Hate. Even as city boosters like Stanley Marcus went on a PR offensive to advertise “What’s Right With Dallas,” citizens did very little to fundamentally change what made Dallas the city that killed the president. Still, perceptions of the city changed with time. In the 1970s Dallas became a city defined by its skyline, football team and oil-soaked soap opera. The city, however, remained divided. The political machine remained in place. Life went on.

Today, we’re still reckoning with the violence we witnessed two years ago. But, hopefully, this time we can turn the trauma of public violence into something positive for the city. If we are spurred by the recognition that violence then and now is, in part, born of the extremes and divisions that define our city, then perhaps we can work towards building a fairer city for all its citizens. This movement is already underway.

For perhaps the first time, Dallas City Hall has recognized the potential of southern Dallas. In 2012, Mayor Mike Rawlings in 2012 launch GrowSouth, an ambitious initiative that looks to foster investment in the south to reduce the disparity between the haves and the have-nots. While GrowSouth supporters have the goals of strengthening neighborhoods, focusing on education and improving the quality of life for those in southern Dallas, perhaps the biggest obstacle is convincing Dallasites that the problems of the south are indeed the problems of the city as a whole.

The most substantive step the city has taken in making ours a fairer city came earlier this year with the adoption of a comprehensive housing policy that aims to increase affordable housing. Supporters of this policy — which the city council approved unanimously — contend that access to affordable housing is the city’s biggest problem and also the best way to attack the segregation that defines the city and the poverty it engenders. The first steps have been stake, but many more remain. Whatever the future holds for Fair Park may not determine the future of southern Dallas at large, but it will certainly show what the city as a whole thinks about its southern half.

That will be a telling reveal, indeed. The violence of that July night two years ago showed us the costs of a divided city. Commemoration of those killed is not enough.

Dallasites would do well to offer more than just an irresolute remembrance of those fallen officers this week. Instead, we should commit ourselves to creating a more equitable, a more just and a more integrated city.

Blake Earle is a historian and Metroplex native. He’s a postdoctoral fellow with the Center for Presidential History at Southern Methodist University. You can find him in person on Lower Greenville, or on Twitter or Instagram at @tbearle.