Sarah Hepola Went From The Circus To The Times' Best Seller List. Here's Where She Did It.

Welcome to Space Invaded, a new recurring feature in which we peer into the desirable workspaces of various Dallas creatives and try keep our envy to a minimum.

If you've been paying attention to the literary world at all this year, the name Sarah Hepola might ring a bell.

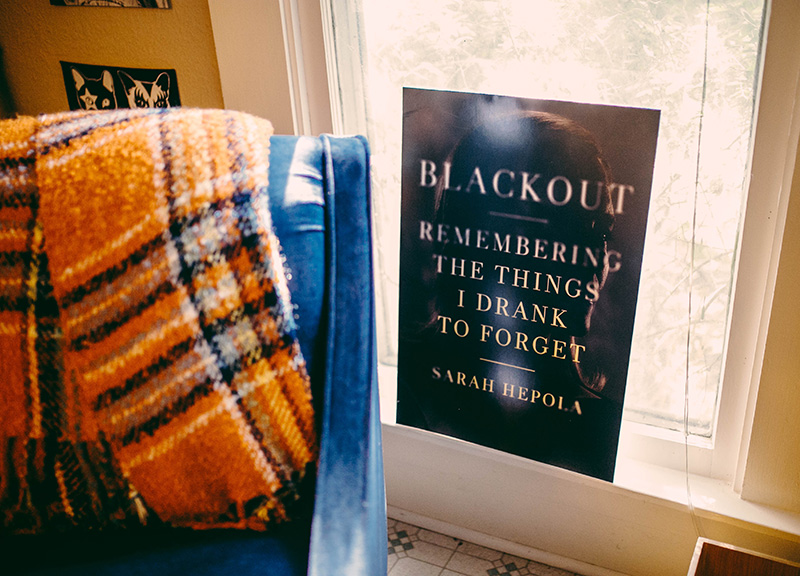

The former Dallas Observer music critic and Salon personal essays editor published a memoir, Blackout: Remembering The Things I Drank to Forget, that ended up on the New York Times Best Seller list. More than that, it's been met with rave reviews by the newspapers that still matter — the Times, other coast's Times, the Chicago Tribune and the Washington Post — and hip web publications alike.

So it's pretty cool that Hepola carved out a little time for a chat with us about her recent successes and about her workspace in her Old East Dallas home, which is full of collected trinkets from thrift stores and the like. Hepola also surrounds herself with a ton of books, just as you might expect: Her congested bookshelves are littered with Stephen King (one of her favorites, and one of the authors who got her into writing) and new kings of the craft (Jonathan Franzen, Jeffrey Eugenides) alike.

Currently, Hepola is adapting her best-selling memoir into a screenplay, which is a full-circle move for the former critic, who says she really wasn't all that great at being a critic in the first place. Her stories, she says, are what she's best at penning.

How'd you get into writing? How so? You're calling the Austin Chronicle the circus? Was it like Slacker? What was the catalyst that got you more involved with personal writing as opposed to criticism Why do you think people liked reading that more? Do you find some of the subject matter in your book — which, let's be clear, is about blacking out from drinking and you coming to terms with the dangers of that — to be embarrassing or shameful? But it's a living breathing thing. That's because there's a stigma behind who owns and loves cats and all that kind of nonsense. One of the reason's I asked that — if you were embarrassed by some of the stuff in the book — is how you get past that initial embarrassment when you're writing? You're going to be widely read. I mean, you have a New York Times Best Seller. How do you come up with ideas? That's one of the most important part about writing — it's not just about being a good writer, you have to come up with good ideas. Why did you decide to write about drinking? Was it written in the '30s or something? No. 1970?

I've been good at writing since I was a little kid. It was one of the first things that I found that I was really good at. So, just like any kid, you go where the praise is. If you get praise for being good at something, you wanna do it more and more. By the time I got to college, I thought I might one day write a novel or I might be a playwright 'cause I was involved in theater, and my college roommate was the editor of the Daily Texan — I went to the University of Texas. She was the editor of the daily paper, which was a big deal. It was a really prestigious position. She asked me if I would come work for the paper and I was like, “I don't know anything about journalism.” I didn't even read newspapers. I was like, “Eh, that's kind of boring.” And she's said, “No, it doesn't matter; you just have to be able to write. And you have to help people write better.” At that point, I was an English-liberal arts major and I had been studying writing, so I went to the paper and it was a whole new universe for me.

I didn't realize you could get paid, today, to go watch movies, to listen to albums, to see plays — all of which I was already doing. So now you're telling me I get to see those things for free and you're going to pay me for it and I will have beer money and pizza money? Absolutely. I'm sold. So that was the whole beginning of a new path for me. I was getting my teaching certification to teach high school English — because I didn't know what else to do as a writer — and I started teaching high school. I was like, “Oh my god, I don't think I can do this.” So, I had been interning at the Austin Chronicle, dabbling doing different things, whatever they asked me to do. And they offered me a job and I took it, and that is the day I joined the circus.

Oh my god, that place! That place in the 1990s…

Oh my god, Slacker! It was Slacker paradise. That movie had been made in the '90s — '92 or '91 — and it had defined that whole era. We wore flip-flops and shorts to work. We got to work at 10:30. I was hungover all the time. My boss, one year for Christmas, drew my name for Secret Santa and gave me one of those hats you put beers on the other side and he gave it to me so I could drink more at work. That was the Austin Chronicle. Also, by the way, it was the greatest education in pop culture and journalism I could have ever dreamed for because I was surrounded by obsessives, OCD sufferers and genuine true blue enthusiasts who lived and breathed the same things I loved all my life: music, film, television, stage, writing, art. They taught me how to read it better and how to know it better, and it was a tremendous education. And it was also a tremendous excuse to drink a great deal and sort of feed my worst impulses, which were drinking a lot, eating a lot, not taking care of myself, sleeping too late and being a general college student through my twenties.

From the Chronicle, I eventually came to Dallas again because I was dating somebody here and I got a job as a music editor. From there, I went to New York and got a job at Salon. I had very few qualifications to be the music editor of the Dallas Observer — other than I could read and write and listen to music. I didn't come in with an encyclopedic knowledge of music. I learned that I was in some ways not a good fit for that job. Each time the publication needed something from me, that allowed me to learn more and grow. Along the way, one of the things I discovered was that I'm really good at personal writing — and I didn't know that. I wanted to be a critic, but I wasn't really knowledgeable enough to be a critic. I have critic friends and they have that incredible, deep, encyclopedic recall that's so spooky, and I just didn't have that. I'm an enthusiast. But I could write stories about myself, and my own emotions and the things that happened in my life and my internal experiences that were better than other people's. Then again, just like when you're a kid, you move towards the praise. I was seeing that there was a way of writing that I was doing that was just me talking about my life that was getting much better responses than everything else I was doing. I could write a review of a movie and everybody was like, “I don't really care.” But, I could write a story about fighting with my boyfriend and playing board games, and suddenly everyone wanted to read that. That was instructive for me. It showed me that I did one thing better, and people liked reading that better. So I kept doing it.

Because people want to know about their own lives. So, people don't really care about my life. I think they care about their own lives. I think they want to be reminded that other people have the same feelings that they do. I think they also wanna place themselves on a hierarchy. When I'm writing about drinking, people wanna know: Do I drink more than her, do I drink less than her? They want to slot themselves. We're always looking to kind of organize who we are and where we stand in the world. If I'm writing about a fight with my boyfriend, OK, is that worse than the fight I had with my significant other? Or is it better? Ooh, she's much crazier than I am — no, wait I'm much crazier than her. It's that we want to know what other people's genuine experiences are like. I think, as humans, we hunger for that. I also think we just like hearing stories. I mean, when I say you don't care about my life, that's not exactly what I mean — because everybody likes telling stories. What they're trying to do is figure themselves out.

Y'know, it's certainly true that people are judging me all the time. People are judging all of us all the time. But something interesting about me — which I think comes from having a therapist mother who taught me from a very young age things that I don't think necessarily sync up with society — is that I'm not embarrassed by this stuff. Y'know what it reminds me of? It reminds me of when I hear Lena Dunham interviewed sometimes. She'll talk about how she's not embarrassed being naked on that show, which blows my mind. You could not pay me enough money to be naked on HBO. Are you fucking kidding me? Never in my life. And that reminds me of a friend of mine, after I was interviewed by Terry Gross on NPR. A friend of mine texted me and she was like, if Terry Gross asked me about my sex life on NPR, I would jump out the window. And it didn't bother me. The subject is very interesting to me, and I'm sure that people are judging me, but they're judging me all the time anyways. For whatever reason, I lack the embarrassment gene on personal information. Now, that doesn't mean I'm not embarrassed by certain things in the book. But they're kind of surprising. I think I'm embarrassed with how deeply connected I was with my cat. It feels a little weak. It feels kind of corny that I was super connected to my cat.

So it's totally understandable right? But, I have a kind of tough girl's sense of like, “That's gonna make me a softie.”

Yeah, but I think will all the blackouts and the drinking and stuff like that, I came of age in the '90s and the aughts, which were a really heavy binge-drinking time in the country, and I really believed full-heartedly this idea that drinking made me cool. And so I might be embarrassed in the sense that I blacked out, and “Ooh, couldn't hold my liquor.” But, like, am I embarrassed to tell people? No.

Y'know, I think that the embarrassment and shame and all of that stuff makes us human, and it's probably just worth knowing. It's a signal for something. It's a red flag. It's tells you something. It tells you that information matters, it threatens the way people see you. Why does that information matter? The introduction of that information might make them change their mind about you. I find it helpful to look almost clinically at things like that. Let me give you this example, which is a little bit different but, but I think a bit similar: Nervousness. When I used to get nervous, I just hated it. I had to drink it away. I hated my nervousness, I wanted it to go away. If I was nervous, I grabbed a drink and it calmed me. And when I was in sobriety, I realized I couldn't do that. And then I realized that nervousness is actually my body's signal to me that this moment matters. There's chemical reactions that happen with nervousness. Your heart speeds up. You get adrenaline in your system, and adrenaline sharpens you. So it's actually your body's appropriate reaction to the moment. I think, in some ways, embarrassment is an appropriate reaction to the moment, which is that you're telling something vulnerable. You have to learn to tolerate the embarrassment a little bit. I found it very useful to just tell people, “Oh my gosh, I'm embarrassed of this moment,” or “That story embarrasses me.” And they get it.

I think you start to look for two things, which is what you want to write and what nobody else is writing. I think the first thing you follow is your own obsession and fascination. It depends. It's gonna be different for every writer. Not every writer is gonna write personal stories. But I think you follow your own fascinations and your own passions and then you compare that against the cultural conversation — what people are interested in now. You want to add to that, but you want to make sure you add something new.

It was all I was thinking about. I was sober and my life sucked. And then I remember going and reading a book in the Barnes & Noble about recovery, and it said something like, “Women are very embarrassed by their drinking,” and I was like, “What the hell is this person talking about?”

It had come out in, like, 2005! But it was based on basically the early 20th century with a long history of women hiding their drinking and being embarrassed by the way that they drink and a long history of women being caretakers for men who did go out to bars. We forget this, but women didn't drink in bars until the 1970s. The first women orders at the bar at McSorley's in the East Village were in 1970!

1970! That's not that long ago! So drinking was in men's spaces and, in the years since — the 1970s, '80s and especially the '90s and the aughts — you just saw this surge in women drinking. And I knew that nobody had written about that in a way that I thought reflected my story.