How One Polyphonic Spree Member Looked Backward To Revolutionize the Microphone Game.

Tom Petty uses one. Erykah Badu does, too. The list goes on: Vampire Weekend, Queens of the Stone Age, Unknown Mortal Orchestra, The Black Keys' Dan Auerbach, Norah Jones, Snoop Dogg, Vincent Gallo — they're just some of the names that employ it.

Yeah, the Copperphone sure is getting around these days — and much more easily now than back when it was publicly believed by the FBI to be a pipe bomb, that's for sure.

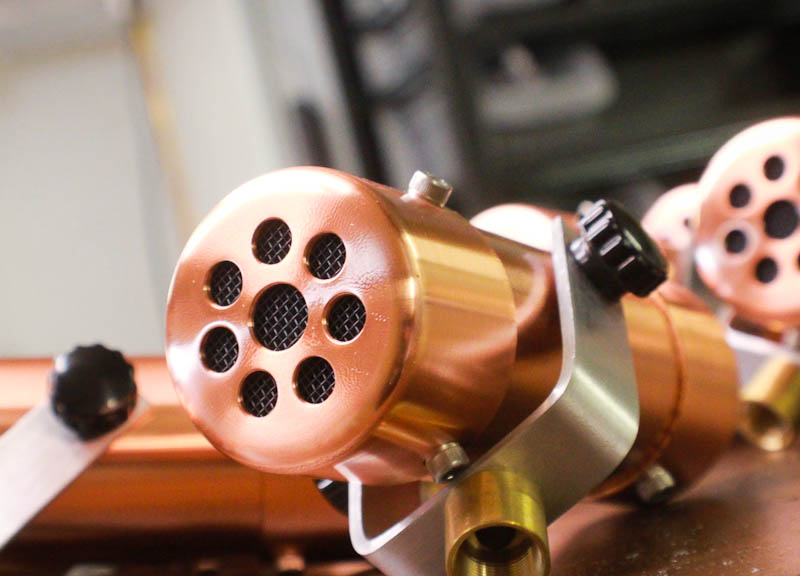

The creation of Mark Pirro, formerly of Tripping Daisy and currently the bassist for The Polyphonic Spree, the Copperphone is pretty much exactly what it sounds like — a copper microphone — that Pirro built at the request of his bandmate Tim DeLaughter, who sought an efficient form through which his vocals could be given a telephone-like quality both in the studio and in live settings.

Now, if you've ever heard your favorite artist trying to sound old-timey, as if they were trying to make Orson Wells jealous, odds are that they accomplished this feat through the use one of Pirro's Copperphones, which he produces in bulk through his Dallas-based sound equipment company, Placid Audio.

'I've helped build microphones for Tom Waits, Johnny Rotton and Green Day — just to name a few,” brags Paul North, who works in Pirro's Placid Audio workshop and himself performs music under his Sunnybrook moniker. “It's just really cool knowing that these microphones are going to big studios where people like Tom Waits are going to be using the products I made.”

It's very cool, actually. And it was just a simple idea that got this sonic revolution started.

“There's an effect unit that can be run at the front of house during a live show,” Pirro says, walking around his workshop and describing the tinny effect that his flagship product offers. “But the sound guy never knows when to engage [it].”

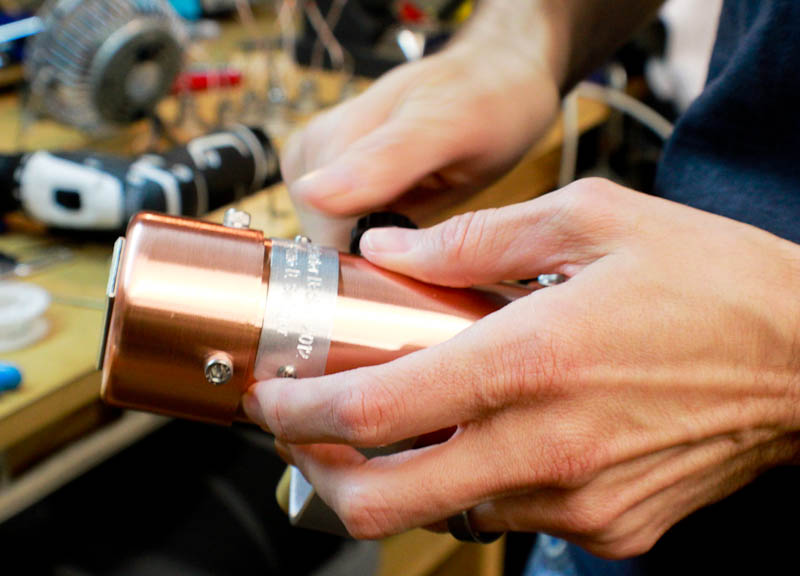

So, at DeLaughter's urging, Pirro got to work, crafting a microphone that does just that. Familiar with tools and mechanics thanks to his upbringing in Detroit, Pirro fashioned the prototype Copperphone out of PVC piping, duct tape and, basically, whatever he could find in his garage. The end result of that first go was an ugly mess — Pirro's quick to acknowledge that much — but it was an effective model. Not only did Pirro's creation work, but it before long started piquing the interest of fellow musicians that he and his Spree bandmates would meet on tour.

“They would ask where to get one,” says Pirro. And so he added microphone-builder to his daily routine and resume, which already found him tinkering away with sounds in his home recording studio.

After nailing down the exact sound quality he was aiming for — a lo-fidelity sheen by most any standards — Pirro headed out to his local hardware store in search of a more presentable product. Copper pipes called out to him from the aisles, and, thus, the Copperphone concept was truly born.

“Then it starts to become a process of streamlining,” Pirro says.

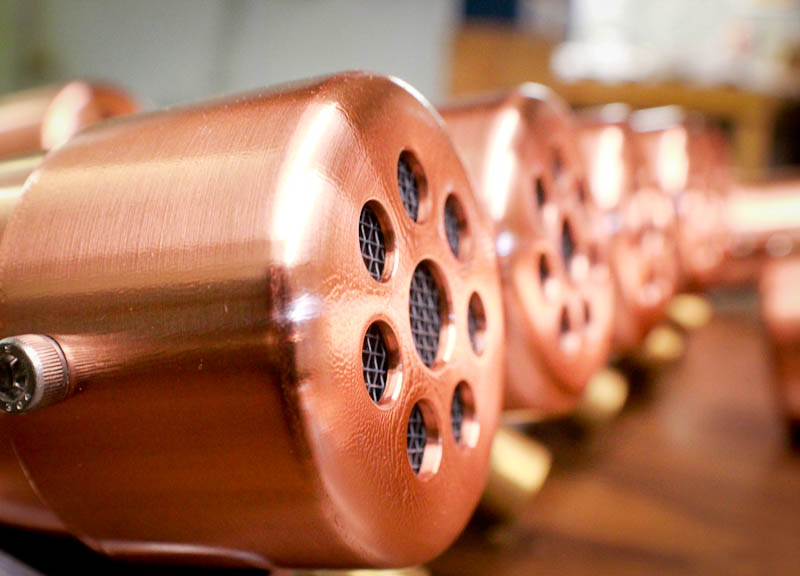

A fully self-taught microphone engineer, he began brainstorming ideas on how to make as many Copperphones as possible in the shortest amount of time. At one point, he turned his garage into a makeshift studio where he made each instrument himself.

“In the beginning, it was exciting,” Pirro says. “I hadn't made very many of them before, so every time I made one it was like a little baby, a creation.”

After the grueling and time-consuming task became too much for Pirro to bear alone, he was able to secure himself a local and modest manufacturing studio where the process became fluid. Soon, he started to hire some local friends and musicians such as North to help him with his production.

Now, on any given day, you can find Pirro and perhaps one other shop hand hand-crafting these fine instruments. And that's just the way Pirro likes it, actually.

“I've gone to trade shows, and people have suggested that I get these made in China,” he says. “I looked into it, but I have an ethical issue against that. Everybody talks about the economy and the United States kind of falling behind and that is the reason. I pride myself on keeping this a homegrown, do-it-yourself kind of business. I just never thought a niche-y product like this would be so well-received. It's enough to make it worth my while to keep doing this, so it's exciting.”

Yes, business is good — but not just because of Pirro and his staff's sweat and effort. The Copperphone's effectiveness as a sonic tool has really started to let the product sell itself.

“I keep it in the room at all times,” says Chris Bell, a Dallas-bred, Grammy-nominated music producer and sound engineer now working out of Blade Studios in Shreveport..

Bell has worked a number of notable artists — Godsmack, The Eagles, recent 35 Denton headliner Solange — and, almost always, he finds a way to use the Copperphone while doing so.

“You can use it on vocals, but it's great for a drum room mic, too,” says Bell, who says he actually rarely uses the Copperphone which now retails on the Placid Audio site for $249.99, for vocals any more. “It's a great mic to give a different color to the music. Honestly, we just keep the thing turned on. You can always use it for something.”

Most recently, Dave Matthews and Jakob Dylan visited Blade Studios and, while on a drunken binge, they excitedly employed the Copperphone to give their upcoming collaborative side project's piano sounds a distant effect. Moments like that one aren't too shabby — especially when you consider how Bell even got his hands on a Copperphone in the first place. Pirro had just started building the microphones and he loaned one to Bell as a toy to test-drive in his studio. Bell never returned that loaner. He says he doesn't plan on doing so any time soon, either.

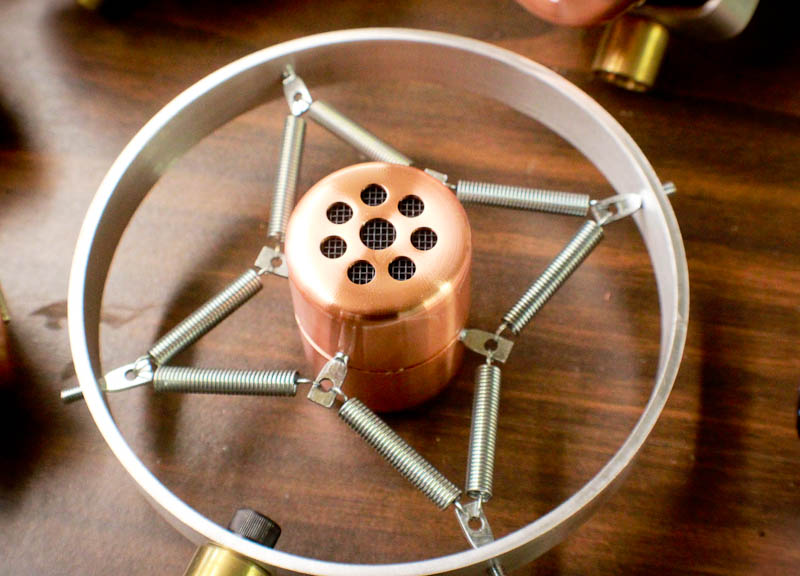

Now, thanks to that kind of Copperphone-related reception, Placid Audio has started to expand; these days, Pirro and his staff are also making a miniaturized, Harmonica version of the Copperphone. They've also started work on a newer concept call the Carbonphone, which offers distortion-like qualities to the sounds it picks up and is built from military-grade air traffic controller headset and tank intercom components. The Carbonphone's still being tested; it's not yet ready for full retail. But its existence alone is no doubt a sign that Placid Audio's got more tricks up its sleeve for the future.

For now, however, Pirro's fine with where Placid Audio sits. His lengthy list of clients gives him some comfort in that regard. But so too do his products' seemingly endless possibilities — possibilities that might seem obvious, if also a little backward.

“Most microphone technology is trying to replicate the experience of human hearing — a perfect, flat frequency response where nothing is colored,” Pirro says. “The idea with Placid Audio is to go the other direction.”